Korolev and Freedom of Space: February 14, 1955–October 4, 1957

The space programs of the cold war adversaries formed a symbiotic relationship—a race in which each competitor spurred the other forward—several years before Sputnik. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, much new information on the prehistory of the Soviet space program became available.5

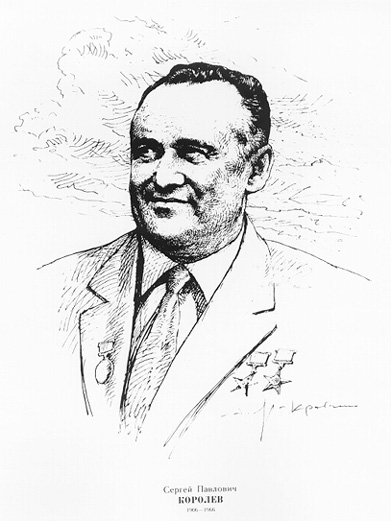

One man dominated Soviet space engineering in the 1950s and 1960s. Sergei Pavlovich Korolev headed a Soviet amateur rocketry organization in the 1930s and survived Joseph Stalin’s forced labor camps to build missiles in the 1940s and 1950s. On May 20, 1954, the Soviet government ordered Korolev’s design bureau, OKB-1, to develop the first Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), the R-7. On May 26, Korolev dispatched to the Soviet government the Report on an Artificial Satellite of the Earth, authored by his old friend Mikhail Klavdiyevich Tikhonravov. He pointed out that the R-7 missile could be used as a satellite launcher and included written materials from the United States that demonstrated American interest in satellite launches.6

Work toward U.S. satellites occurred on several levels in the early 1950s. Civilian interest centered on the possibility of launching science satellites during the IGY. At the same time, the military carried out several reconnaissance satellite studies. The major issue affecting the timing of subsequent U.S. satellite launches apparently emerged as early as June 1952 in the "Beacon Hill Report," authored by a fifteen-person study group convening at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The report pointed out that military satellites would orbit over Soviet territory and could thus be considered a violation of national sovereignty. For this reason, the report stated, their deployment would have to be authorized at the U.S. presidential level.7

On February 14, 1955, the Technological Capabilities Panel ("the Surprise Attack Panel") issued its report, Meeting the Threat of Surprise Attack, in which it reiterated the Beacon Hill group’s contention and suggested a solution. The panel advised that a small science satellite should be launched as early as possible to establish the principle of "freedom of space" for military satellites that would follow.8 President Eisenhower’s advisers adopted the principle of "freedom of space" soon thereafter.9

By this time, the discussion of a science satellite was well advanced in U.S. scientific circles. This culminated in a U.S.-sponsored initiative prompting the international ruling body of the IGY to call for science satellite launches during the IGY. The resolution was adopted in Rome on October 4, 1954.

The Rome resolution pulled back the hammer on the starter’s gun in the satellite race. It helped ensure that Korolev’s preliminary satellite work did not languish, and it led to the creation of the Interdepartmental Commission for the Coordination and Control of Work in the Field of Organization and Accomplishment of Interplanetary Communications, the first organization within the Soviet Academy of Sciences devoted to spaceflight.10 This organization, the existence of which was announced on April 16, 1955, was chaired by Academician Leonid Sedov.

A month before Sedov’s announcement, on March 14, 1955, the U.S. National Committee for the IGY had issued a report declaring feasible a U.S. science satellite launch during the IGY. It submitted the report to the National Science Foundation, which took it to President Eisenhower. On May 18, 1955, the U.S. IGY committee formally approved the satellite project. The National Security Council (NSC) considered the project on May 20, 1955, and issued a draft policy statement (NSC 5520). On May 26, 1955, the NSC formally approved U.S. government participation in the U.S. IGY science satellite project. The NSC’s unstated aims were to establish the principle of "freedom of space" and to accrue for the United States the prestige benefits of launching the first satellite. The IGY science satellite program was not to interfere with high-priority missile programs.11 On May 27, Eisenhower approved the plan. On July 29, 1955, Eisenhower’s press secretary, James Hagerty, announced that the United States would launch a science satellite during the IGY.

Without realizing it, Eisenhower fired the starter’s gun in the race to launch an Earth satellite. News of the announcement reached the 6th International Astronautical Congress in Copenhagen, Denmark, on August 2, 1955, where Academician Sedov was in attendance. That same day, Sedov held a press conference at the Soviet Embassy in Copenhagen, at which he announced that "the realization of the [Soviet] satellite project can be expected in the near future."12

On August 30, 1955, Korolev presented to the Soviet government’s Military-Industrial Commission a new satellite report completed two weeks earlier by Tikhonravov. On the basis of the report, the commission approved using the R-7 ICBM to launch a one-and-a-half-ton satellite—this over opposition from Soviet missile specialists, who worried that the satellite effort would interfere with ballistic missile development. Later that day, Korolev told representatives of the Soviet Academy of Sciences that he could launch the first in a series of IGY science satellites in April–June 1957, before the IGY started. The Academy representatives approved the project. Work on the satellite’s scientific program began immediately, but the Soviet Council of Ministers did not issue its formal decree authorizing the program (No. 149-88ss) until January 30, 1956.13 The satellite was designated Object-D.

During the following month, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev visited OKB-1 to see the R-7 missile. Korolev made the most of the opportunity. He displayed an Object-D mockup and described U.S. satellite plans. Khrushchev expressed concern that the satellite program might interfere with missile work, but he accepted Korolev’s assurances to the contrary and endorsed the program.14

One of Korolev’s selling points was that the R-7 ICBM was well along in development. It therefore stood a good chance of launching the first satellite because the United States had elected to build an entirely new rocket for its satellite effort. The Soviet engineer’s assessment was not far off the mark.

On August 3, 1955, the Stewart Committee had approved the Project Vanguard plan of the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) for an IGY science satellite. This committee was chaired by Homer Stewart of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) at the California Institute of Technology, and it consisted of eight members appointed by the Department of Defense and the branch services. The committee chose Vanguard from a field of three rival projects: the Air Force’s "World Series" plan, which envisioned launching a satellite weighing about 2,500 kilograms (about 5,000 pounds) on an Atlas missile with an upper stage; the Army’s Project Orbiter, which proposed to launch a five-pound, poorly instrumented satellite on a Redstone missile with a Loki upper stage; and Vanguard, which had going for it an impressive suite of science instruments but which required the development of a new rocket based partly on the Viking sounding rocket. The Air Force plan was eliminated because it might interfere with missile development. The Stewart Committee had difficulty choosing between the Army and NRL plans. The Army booster clearly won out over the Vanguard rocket, which existed only on paper, while the NRL satellite’s impressive instrument complement was in keeping with the scientific spirit of the IGY. For a time, the committee considered launching the NRL satellite on the Army booster, but its members worried that interservice rivalry might delay the satellite past the IGY.15 By some accounts, the final vote could have gone for either Orbiter or Vanguard, and it may in fact have been decided in the end by the absence of one member because of illness.16

The Vanguard program was officially started on September 9, 1955, with a plan to build six vehicles. Of these, one was expected to reach orbit. The program had a budget of $20 million and an eighteen-month timetable leading to first orbital launch. The Object-D program began officially on February 25, 1956, with satellite assembly beginning on March 5 and launch targeted for the spring of 1957.17 Both the U.S. and Soviet programs immediately fell behind schedule.

On September 14, 1956, Korolev addressed the Presidium of the Soviet Academy of Sciences to plead for additional support in meeting the target launch date. He complained that subcontractors were not making required deliveries. Korolev had become anxious when he received a report—mistaken, as it turned out—that a September 1956 missile test at Cape Canaveral had been a failed satellite launch attempt.

In addition, the R-7 engine modified for satellite launches was not performing at the thrust level expected. Korolev drove himself and his staff mercilessly to solve the problem, but he finally had to change his plans. On January 5, 1957, he formally proposed reducing the weight of the first Soviet satellite to improve its chances of being first in space. He cited the supposed failed U.S. satellite launch and his belief that the United States could try again in early 1957. In fact, Korolev proposed two "simple satellites." PS-1 and PS-2, as they were known, would each weigh about 100 kilograms (220 pounds). The Soviet Council of Ministers approved the change on February 15, 1957.18

Korolev did not need to drive himself and his staff so hard, for in the United States, Vanguard also had problems. Between September 1955 and April 1957, the program’s cost shot up from $20 million to $110 million. On May 3, 1957, the Bureau of the Budget sent an urgent memorandum on the overruns to President Eisenhower. He placed the issue on the agenda of the May 10 NSC meeting.

John Hagen, Vanguard’s program director, and Detlov Bronk, president of the National Academy of Sciences, may have felt buoyed by the successful second Vanguard test launch on May 1. TV-1, as it was known, tested a rocket consisting of a liquid-fueled Vanguard first stage (a modified Viking sounding rocket) and a prototype solid-fueled Vanguard third stage. Hagen attempted to justify the program on the basis of its expected scientific return, and Bronk appealed to Eisenhower’s vision of the future, declaring that the first satellite launch would mark the start of a new historical epoch. The President, however, would have none of that—he kept the discussion focused on Vanguard’s escalating cost. Eisenhower complained that the scientists had "gold-plated" their instruments and produced plans for satellites larger and more elaborate than those he had approved. The act of launching the satellite was what would create prestige, not the instruments it carried, he said. ("Freedom of space" was not directly mentioned, although the NSC 5520 directive was.) Eisenhower grudgingly admitted that the United States had little choice but to continue the costly program because it had publicly announced that it would launch a satellite. He insisted, however, that the total cost be held to $110 million. He stated that, while six Vanguards were being built, there was no reason to suppose that all six would be launched. The Vanguard program might end as soon as it succeeded in placing a satellite in orbit. There was little hint of urgency.19

The IGY began on July 1, 1957, and a few days later, on July 5, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) reported to Deputy Secretary of Defense Donald Quarles that a Soviet satellite launch might occur as early as the birthday anniversary of Russian rocket pioneer Konstantin Tsiolkovskiy on September 17. This intelligence apparently excited little interest among members of the Eisenhower administration who learned of it.20 Korolev might have been gratified at the time to know that the CIA supposed that he might launch a satellite as early as September, for his R-7 rocket was having trouble. By the end of July, it failed three times in succession. Finally, on August 21, 1957, the missile flew successfully for the first time. The flight was announced to the world on August 27, but many in the United States were skeptical that the Soviets had accomplished the world’s first ICBM test. A second, less publicized test on September 7 was also successful.

The September 17 target date had to slip, however. On September 20, the State Commission for the PS-1 satellite authorized an October 6 launch from Baikonur Cosmodrome in Soviet Kazakhstan. Fearful that the United States might launch its satellite during the September 30–October 5 IGY Rockets and Satellites Conference in Washington, Korolev advanced PS-1’s launch to October 4.21 The R-7 rocket modified for launching PS-1 was placed on the pad on October 3. Fueling began at 5:45 a.m., Baikonur time, the next day, and the rocket lifted off sixteen hours later. Six minutes after liftoff, PS-1—soon renamed Sputnik—ejected from its expended carrier rocket to became a second moon of Earth. A new age of exploration was under way.

- Drawing on this new information, Asif A. Siddiqi has recently published a revealing account of events in the Soviet Union leading up to Sputnik’s launch. See Asif A. Siddiqi, "Korolev, Sputnik, and the International Geophysical Year" (https://history.nasa.gov/sputnik/siddiqi.html). Similarly, R. Cargill Hall used recently declassified U.S. documents to trace the Eisenhower administration policy decisions that reined in the U.S. satellite program in the years immediately prior to Sputnik. See R. Cargill Hall, "Origins of U.S. Space Policy: Eisenhower, Open Skies, and Freedom of Space," in John M. Logsdon, gen. ed., with Linda J. Lear, Jannelle Warren-Findley, Ray A. Williamson, and Dwayne A. Day, Exploring the Unknown: Selected Documents in the History of the U.S. Civil Space Program, Volume I: Organizing for Exploration (Washington, DC: NASA SP-4407, 1995), pp. 213–29. Together, these articles paint a coherent picture of events in the United States and the Soviet Union leading up to the start of the space age.X

- Siddiqi, "Korolev, Sputnik, and the IGY."X

- Hall, "Origins of U.S. Space Policy," p. 217.X

- Ibid., p. 220.X

- Ibid., p. 221.X

- Siddiqi, "Korolev, Sputnik, and the IGY."X

- National Security Council, NSC 5520, "Draft Statement of Policy on U.S. Scientific Satellite Program," May 20, 1955, in Logsdon, gen. ed., Exploring the Unknown, 1: 308–13.X

- Siddiqi, "Korolev, Sputnik, and the IGY."X

- Ibid.X

- Asif Siddiqi, personal communication.X

- Holmes, The Race for the Moon, p. 51.X

- Green and Lomask, Vanguard: A History, p. 48.X

- Siddiqi, "Korolev, Sputnik, and the IGY."X

- Ibid.X

- "Memorandum of Discussion at the 322d Meeting of the National Security Council, Washington, D.C., May 10, 1957," in Logsdon, gen. ed., Exploring the Unknown, 1: 324–28.X

- Allen W. Dulles, Director of Central Intelligence, to The Honorable Donald Quarles, Deputy Secretary of Defense, July 5, 1957, in Logsdon, gen. ed., Exploring the Unknown, 1: 329–30.X

- Siddiqi, "Korolev, Sputnik, and the IGY."X