Trips to the Moon

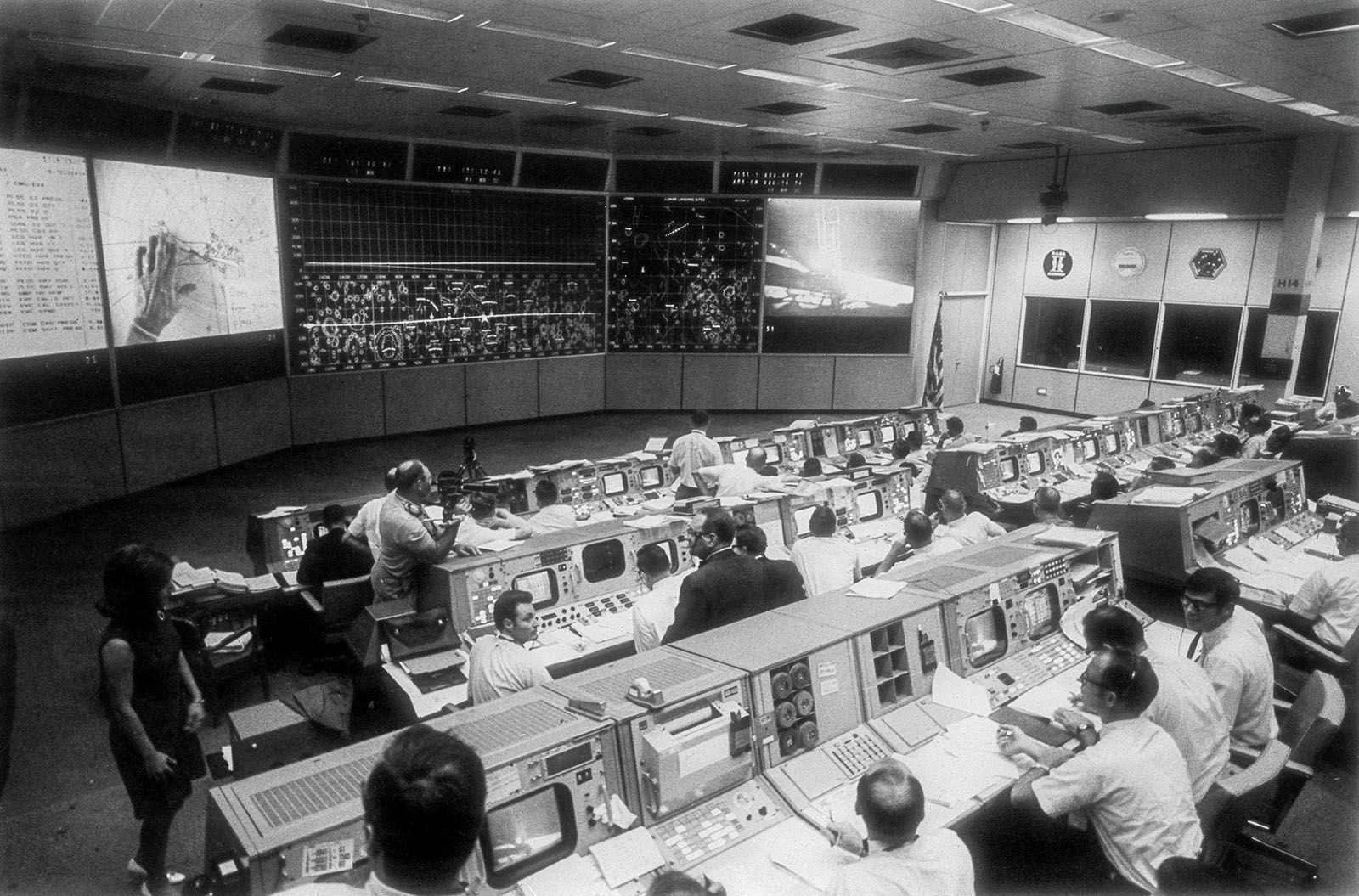

After a piloted orbital mission to test the Apollo equipment on October 1968, on 21 December 1968 Apollo 8 took off atop a Saturn V booster from the Kennedy Space Center with three astronauts aboard—Frank Borman, James A. Lovell, Jr., and William A. Anders—for a historic mission to orbit the Moon.83 At first it was planned as a mission to test Apollo hardware in the relatively safe confines of low Earth orbit, but senior engineer George M. Low of the Manned Spacecraft Center at Houston, Texas, and Samuel C. Phillips, Apollo Program Manager at NASA headquarters, pressed for approval to make it a circumlunar flight. The advantages of this could be important, both in technical and scientific knowledge gained as well as in a public demonstration of what the U.S. could achieve.84 So far Apollo had been all promise; now the delivery was about to begin. In the summer of 1968 Low broached the idea to Phillips, who then carried it to the administrator, and in November the agency reconfigured the mission for a lunar trip. After Apollo 8 made one and a half Earth orbits its third stage began a burn to put the spacecraft on a lunar trajectory. As it traveled outward the crew focused a portable television camera on Earth and for the first time humanity saw its home from afar, a tiny, lovely, and fragile “blue marble” hanging in the blackness of space. When it arrived at the Moon on Christmas Eve this image of Earth was even more strongly reinforced when the crew sent images of the planet back while reading the first part of the Bible—“God created the heavens and the Earth, and the Earth was without form and void”—before sending Christmas greetings to humanity. The next day they fired the boosters for a return flight and “spashed down” in the Pacific Ocean on 27 December. It was an enormously significant accomplishment coming at a time when American society was in crisis over Vietnam, race relations, urban problems, and a host of other difficulties. And if only for a few moments the nation united as one to focus on this epochal event. Two more Apollo missions occurred before the climax of the program, but they did little more than confirm that the time had come for a lunar landing.85

Then came the big event. Apollo 11 lifted off on 16 July 1969, and after confirming that the hardware was working well began the three day trip to the Moon. At 4:18 p.m. EST on 20 July 1969 the LM—with astronauts Neil A. Armstrong and Edwin E. Aldrin- -landed on the lunar surface while Michael Collins orbited overhead in the Apollo command module. After checkout, Armstrong set foot on the surface, telling millions who saw and heard him on Earth that it was “one small step for man—one giant leap for mankind.” (Neil Armstrong later added “a” when referring to “one small step for a man” to clarify the first sentence delivered from the Moon’s surface.) Aldrin soon followed him out, and the two plodded around the landing site in the 1/6 lunar gravity, planted an American flag but omitted claiming the land for the U.S. as had been routinely done during European exploration of the Americas, collected soil and rock samples, and set up scientific experiments. The next day they launched back to the Apollo capsule orbiting overhead and began the return trip to Earth, splashing down in the Pacific on 24 July.86

These flights rekindled the excitement felt in the early 1960s with John Glenn and the Mercury astronauts. Apollo 11, in particular, met with an ecstatic reaction around the globe, as everyone shared in the success of the mission. Ticker tape parades, speaking engagements, public relations events, and a world tour by the astronauts served to create good will both in the U.S. and abroad.

Five more landing missions followed at approximately six month intervals through December 1972, each of them increasing the time spent on the Moon. Three of the latter Apollo missions used a lunar rover vehicle to travel in the vicinity of the landing site, but none of them equaled the excitement of Apollo 11. The scientific experiments placed on the Moon and the lunar soil samples returned through Project Apollo have provided grist for scientists' investigations of the Solar System ever since. The scientific return was significant, but the Apollo program did not answer conclusively the age-old questions of lunar origins and evolution.87

In spite of the success of the other missions, only Apollo 13, launched on 11 April 1970, came close to matching earlier popular interest. But that was only because, 56 hours into the flight, an oxygen tank in the Apollo service module ruptured and damaged several of the power, electrical, and life support systems. People throughout the world watched and waited and hoped as NASA personnel on the ground and the crew, well in their way to the Moon and with no way of returning until they went around it, worked together to find a way safely home. While NASA engineers quickly determined that air, water, and electricity did not exist in the Apollo capsule sufficient to sustain the three astronauts until they could return to Earth, they found that the LM—a self-contained spacecraft unaffected by the accident—could be used as a “lifeboat” to provide austere life support for the return trip. It was a close-run thing, but the crew returned safely on 17 April 1970. The near disaster served several important purposes for the civil space program—especially prompting reconsideration of the propriety of the whole effort while also solidifying in the popular mind NASA’s technological genius.88

- Space Flight: The First 30 Years, p. 14.X

- NASA, Apollo Program Director, to NASA, Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight, “Apollo 8 Mission Selection,” 11 November 1968, Apollo 8 Files, NASA Historical Reference Collection.X

- Rene Jules Dubos, A Theology of the Earth (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1969), pp. 1-3; Oran W. Nicks, ed., This Island Earth (Washington, DC: NASA SP-250, 1970), pp. 3-4; R. Cargill Hall, “Project Apollo in Retrospect,” 20 June 1990, pp. 25-26, R. Cargill Hall Biographical File, NASA Historical Reference Collection.X

- Neil A. Armstrong, et al., First on the Moon: A Voyage with Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins and Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr., Written with Gene Farmer and Dora Jane Hamblin (Boston: Little, Brown, 1970); Neil A. Armstrong, et al., The First Lunar Landing: 20th Anniversary/as Told by the Astronauts, Neil Armstrong, Edwin Aldrin, Michael Collins (Washington, DC: NASA EP-73, 1989); John Barbour, Footprints on the Moon (Washington, DC: The Associated Press, 1969); CBS News, 10:56:20 PM EDT, 7/20/69: The Historic Conquest of the Moon as Reported to the American People (New York: Columbia Broadcasting System, 1970); Henry S.F. Cooper, Apollo on the Moon (New York: Dial Press, 1969); Tim Furniss, “One Small Step”—The Apollo Missions, the Astronauts, the Aftermath: A Twenty Year Perspective (Somerset, England: G.T. Foulis & Co., 1989); Richard S. Lewis, Appointment on the Moon: The Inside Story of America’s Space Adventure (New York: Viking, 1969); John Noble Wilford, We Reach the Moon: The New York Times Story of Man’s Greatest Adventure (New York: Bantam Books, 1969).X

- On these missions see, W. David Compton, Where No Man Has Gone Before: A History of Apollo Lunar Exploration Missions (Washington, DC: NASA SP-4214, 1989); Stephen G. Brush, “A History of Modern Selenogony: Theoretical Origins of the Moon from Capture to Crash 1955-1984,” Space Science Reviews, 47 (1988): 211-73; Stephen G. Brush, “Nickel for Your Thoughts: Urey and the Origin of the Moon,” Science, 217 (3 September 1982): 891-98.X

- United States Senate, Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, Apollo 13 Mission. Hearing, Ninety-first Congress, second session. April 24, 1970 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1970); United States Senate, Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, Apollo 13 Mission. Hearing, Ninety-first Congress, second session. June 30, 1970 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1970); Henry S.F. Cooper, Jr., Thirteen: The Flight that Failed (New York: Dial Press, 1973); “Four Days of Peril Between Earth and Moon: Apollo 13, Ill-Fated Odyssey,” Time, 27 April 1970, pp. 14-18; “The Joyous Triumph of Apollo 13,” Life, 24 April 1970, pp. 28-36; NASA Office of Public Affairs, Apollo 13: “Houston, We've Got a Problem” (Washington, DC: NASA EP-76, 1970).X