Trip to Tranquility

1969: July

In the summer of 1968, a group led by John R. Sevier in Houston studied hundreds of possible lunar landing sites. A lot was involved in setting the lunar module down on the moon - keeping the vehicle stable; gauging surface slopes and boulder distribution; controlling forward, lateral, and vertical speeds during the final few seconds before committing to a landing; and finally cutting off the engine at the proper instant. The spacecraft was equipped to make an automatic, hands-off landing, but analyses of site survey photographs indicated that in such a landing the vehicle would overturn 7 out of 100 times. Sevier’s group contended that a manually controlled touchdown by the astronauts faced better odds. Using a lunar surface model complete with craters and hills and illuminated to match a particular time and date, the analysts demonstrated that the pilots could recognize the high slopes and craters in time to fly over and land beyond them and that there would be enough fuel to do this. Many of the suggested areas were eliminated on the basis of these studies; the list of candidate sites was pared to five for Apollo 11. When Site 2, in the Sea of Tranquility,* was chosen for the target in the summer of 1969, a waiting world watched and hoped that the space team’s confidence was warranted.1

- Site 2 was on the east central part of the moon in southwestern Mare Tranquillitatis. It was about 100 kilometers east of the rim of Crater Sabine and 190 west southwest of Crater Maskelyne - latitude 0 degrees 43' 56" north, longitude 23 degrees 38' 51" east.

The Outward Voyage

On 16 July, the weather was so hot, one observer noted, that the air felt like a silk cloth moving across his face. Nearly a million persons crowded the Florida highways, byways, and beaches to watch man’s departure from the earth to walk on the moon. Twenty thousand guests looked on from special vantage points; one,* leading a poor people’s protest march against the expense of sending man to the moon, was so awed that he forgot for a moment what he came to talk about. Thirty-five hundred representatives of the news media from most of the Western countries and much of the eastern hemisphere (118 from Japan, alone) were there to record the mission in newsprint for readers and to describe the scene for television and radio audiences, numbering according to various estimates as many as a billion watchers.2

Neil Armstrong, Edwin Aldrin, and Michael Collins must certainly have realized the significance of their date with destiny, even though all three were seasoned space travelers. But the normal launch day routine was observed. Donald Slayton rousted the crew out of bed about 4:00 in the morning. Nurse Dee O’Hara recorded a few physical facts, physicians made a quick check, and the astronauts ate breakfast. Waiting to help them into their suits when they finished was Joe Schmitt, the astronauts’ launch-day valet for the past eight years. After they arrived at the launch complex, still another old friend and veteran from Mercury and Gemini days, pad leader Guenter Wendt, assisted them into the spacecraft seats. Armstrong crawled in first and settled in the left-hand couch. Collins followed him, easing into the couch on the right side. As they wriggled into position, were strapped in, and checked switches and dials, Aldrin enjoyed a brief interlude outside on the white room flight deck, letting his mind drift idly from subject to subject, until it was time for him to slide into the center seat. When the hatch snapped to, the threesome was buttoned up from one world, waiting for the Saturn V to boost them to another.3

A Saturn V liftoff is spectacular, and the launch of Apollo 11 was no exception. But it didn’t give the audience any surprises. To the three Gemini-experienced pilots, who likened the sensation to the boost of a Titan II, it was a normal launch. The 12 seconds the lumbering, roaring Saturn V took to clear the tower on the Florida beach did seem lengthy, however. At that point in the flight, a four-shift flight control team in Texas, presided over by mission director George Hage and flight director Clifford E. Charlesworth, assumed control of the mission. The controllers, and the occupants of the adjacent rooms crammed with supporting systems and operations specialists, had little to worry about. Unlike the three Saturn Vs that had carried men into space previously, this one had no pogo bounce whatsoever. Collins and Armstrong had noticed before launch that the contingency lunar sample pouch on Armstrong’s suit leg was dangerously close to the abort handle. If it caught on the handle, they could be unceremoniously dumped into the Atlantic. Although Armstrong had shifted the pouch away from the handle, they worried about it until they attained orbital altitude. Then the crew settled down to give the machine a good checkout. Armstrong found he could not hear the service module’s attitude thrusters firing; but Charlesworth’s flight controllers told him they were behaving beautifully.4

To Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins, the real mission would not start until they went into lunar orbit and separated the lunar module from the command module. To constrain their emotions and conserve their energies, they had decided to spend the first part of the trip resting, eating, and keeping themselves relaxed. If their matter-of-fact behavior and conversation before they went charging off to the moon on a direct course were any indication, they succeeded. Armstrong and Aldrin became drowsy before the engine firing that thrust them onto the lunar path - translunar injection - although Armstrong did murmur a mild “Whew,” when it began. Aldrin casually observed that the S-IVB stage was a “tiny bit rattly,” and Collins uneasily eyed a camera overhead during the 1.3-g acceleration loads, even though he knew it was fastened down securely enough not to bang him on the head. Like their predecessors, they had the upside-down sensation for a while, and Collins, who had to get out of his couch to work with the navigation equipment in the lower bay, was careful to move his head slowly, to guard against getting sick. But none of the three had any physical problems.5

The trip to the moon was quite pleasant. The crewmen ate and slept well, lodging themselves comfortably in favorite niches about the cabin. What work there was to do they enjoyed doing. Collins loved flying the spacecraft - no comparison with the simulator at all, he said - when he pulled the command module away from the S-IVB stage and then turned around to dock with the lunar module. But he was miffed at having to use extra gas from his thruster supply; it was like going through a bad session on the trainer, he fumed. Armstrong was delighted that there was not one scratch on the probe. The command module pilot had a momentary scare when he unstowed the probe and noticed a peculiar odor in the tunnel, like burned electrical insulation - but he could find nothing wrong. They relaxed again and began taking off their suits. Armstrong and Aldrin were especially careful to guard against snags; their lives would depend on these garments in a few days.

Their path to the moon was accurate, requiring only one midcourse correction, a burst from the service propulsion engine of less than three seconds to change the velocity by six meters per second. Not having much to do gave the pilots an opportunity to describe what they were seeing and, through color television, to share these sights and life inside a lunar-bound spacecraft with a worldwide audience. They compared the deeper shades of color their eyes could see on the far away earth with those Houston described from the television transmission. Aldrin, pointing the camera, once asked CapCom Charles Duke to turn the world a bit so he could see more land and less water. After one particularly bright bit of repartee, Duke accused Collins of using cue cards; but the command module pilot replied firmly that there was no written scenario - “We have no intention of competing with the professionals, believe me,” he said. The crew also received a daily news summary, a tradition dating from the December 1965 Gemini VII mission. During one of these sessions, the crew learned the latest news on <cite>Luna 15,</cite> the unmanned Russian craft launched 13 July and expected to land on the moon, scoop up a sample, and return to the earth.** Several times thereafter the trio asked about the progress of this flight.6

On Saturday, 19 July, almost 62 hours after launch, Apollo 11 sailed into the lunar sphere of influence. Earlier, television viewers in both hemispheres had watched as the crew removed the probe and drogue and opened the tunnel between the two craft. Aldrin slid through, adjusted his mind to the new body orientation, checked out the systems, and wiped away the moisture that had collected on the lunar module windows, while the world watched over his shoulder. The pilots were glad to get the tunnel open and the probe and drogue stowed a day early - especially Collins, who had worried about the reliability of this equipment ever since his first sight of it years before.

As the moon grew nearer and the view filled three-quarters of the hatch window, Armstrong discussed lunar descent maneuvers with the flight controllers. He was glad to learn that the service module engine had performed as well in flight as it had during ground tests. The last kilometers on the route were as uneventful as the first. The pilots maintained their mental ties with the earth, enjoying the newscasts radioed to them and the knowledge that their own voyage was front page news everywhere. Even the Russians gave them top billing, calling Armstrong the “czar” of the mission. (At one time, when flight control called for the commander, Collins replied that “the Czar is brushing his teeth, so I’m filling in for him.”) Had the news copy been available to them, they could have read it without difficulty by the light of the earthshine.

A day out from the moon, the crewmen saw a sizable object out the window, which they described variously as a cylinder, something L-shaped like an open suitcase, an open book, or even a piece of a broken antenna. All three believed that it had come from the spacecraft. Collins at first said he had felt a distinct bump; after thinking it over, he decided it must have been his imagination - the modular equipment stowage assembly in the lunar module descent stage had not really fallen off. Or had it? Whatever it was, it was interesting; the crew talked quite a bit about it after returning to earth.

- Dr. Ralph D. Abernathy.

- Luna 15 entered lunar orbit 17 July and made 52 revolutions of the moon before hardlanding on the surface. Unmanned Luna 16, launched by the U.S.S.R. on 12 Sept. 1970, softlanded with an earth-operated drill and returned a recovery capsule containing a cylinder of lunar soil to the earth on 24 Sept. Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, Soviet Space Programs, 1971-75, Staff Report prepared by Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress, vol. 1, 30 Aug. 1976, pp. 145-49.

In Lunar Orbit

Seventy-six hours after leaving the earth, Apollo 11 neared its goal. CapCom Bruce McCandless gave the crew the usual “see you on the other side,” as the spacecraft went behind the moon. Looking at the surface, Collins said it looked “plaster of Paris gray.” Like earlier commanders, Armstrong had to remind his crew not to look at it because they had to concentrate on the first lunar orbit insertion maneuver to get into a nice elliptical flight path. The astronauts agreed that changing sun angles produced different shades of gray and tan. Some of their descriptions of the back, as well as the front, of the moon were graphic. They also hoped no new meteors like those that had caused the lunar craters would fall while they were on the surface. Once Collins mentioned that the desolate Sea of Fertility had certainly been miscalled, and Armstrong gave him a short lecture on how it got its name. They shared the view of the near-earth side of the moon with television watchers back home. Pilots and observers alike could see that the planned landing area was still in darkness but getting brighter each time they flew over it. The astronauts commented that they certainly realized they were circling a smaller body than the earth, but they quickly became used to seeing “the moon going by.” Collins complained once that the “LM just wants to head down towards the surface,” and McCandless answered, “that’s what [it] was built for.”*

During the first two revolutions, the crewmen checked navigation and trajectory figures and then fired the service module engine against the flight path to drop Apollo 11 into a nearly circular orbit. As they watched the landing area grow brighter and brighter, they rested, ate, slept, and rechecked the lunar module systems. Because of the discussions, photographs, and motion pictures provided by the Borman and Stafford crews, the Armstrong team felt as though they were flying over familiar ground. Aldrin said that the view was better from the lunar module than from the command module.

At the beginning of the nine-hour rest period before Armstrong and Aldrin crawled into the lunar module and headed for the lunar surface, Collins urged his companions to leave the probe in the command module. Since this would shorten their preparations for the lunar descent, they were not hard to convince. They knew it would be wise to get as much rest as possible before they set out on that trip but none of the three slept as well as they had on previous nights - it was just not possible to dismiss the next days’ momentous events from their minds. They were test pilots, but they were human.7

After breakfast on Sunday morning, 20 July, Armstrong and Aldrin floated through the tunnel and into the lunar module. Their preparations had been so thorough that they had little to do except wait for Collins to close off the two vehicles. Collins slipped the probe and drogue smoothly into place and then asked the lunar module crewmen to be patient while he went through the checklist. Feeling that he was part of a three-ring circus and appearing simultaneously in each ring, Collins raced around, setting cameras up in windows to photograph the separation, purging the fuel cells of excess water, and getting ready to vent the air pressure from the tunnel. On the back of the moon, during the 13th revolution, everything was ready, which gave him a short breather before the lunar module left. When he asked, “How’s the Czar over there?” Armstrong replied, “Just hanging on - and punching [buttons].” Collins urged the lunar pilots to take it easy on the surface - he did not want to hear any “huffing and puffing.” And so they parted, as Armstrong called out, “The Eagle has wings.”

Armstrong and Aldrin began checking the lander’s critical systems. One of these made everyone a little nervous. They had to turn off the descent stage batteries to see how those in the ascent stage were operating. If they were not working properly, every electrically powered system in the cabin would be affected. But the ascent stage performed beautifully. Next they fired the thrusters and marveled at the ease with which the Eagle flew in formation with Columbia. Aldrin turned on the landing radar, and it also worked properly. Collins broke in to ask them to turn on their blinking tracking light, and Aldrin replied that it was on.

Meanwhile, Collins found that the command ship was also stable. Sometimes the automatic attitude thrusters did not have to make corrections oftener than once in five minutes. Once his vehicle bucked when he inadvertently brushed against the handcontroller, but he quickly stilled the motion. Soon he reestablished contact with flight control and reported that the Eagle was coming around the corner.8

- The lunar module, which weighed more than the command and service modules combined, was feeling the pull of the moon’s gravity.

The First Landing

Now the world could only listen and pray as it waited for the landing, which was not televised. The 12 minutes that it took to set the Eagle down on the lunar surface seemed interminable. After getting a go from flight control, Armstrong advanced the throttle until the descent engine reached maximum thrust, which took 26 seconds. Collins had seen the lander through the sextant from as far away as 185 kilometers, but he could not see it fire 220 kilometers ahead of him. Armstrong was not sure at first that the descent engine had ignited, as he neither heard nor felt it firing. But his instrument panel told him everything was in order. At 10-percent throttle, deceleration was not detectable; at 40- to 100-percent, however, there were no doubts. The lander was much more fun to fly than the simulator. Then, five minutes into the maneuver, the crewmen began hearing alarms. On one occasion, the computer told them a switch was in the wrong position, and they corrected it. Another time, they could find no reason for the alarm, but they juggled the switches and the clanging stopped.

Coping with these alarms, some of which were caused by computer overloads, lasted four minutes. Flight control was watching closely and passing on the information that there was no real problem with their vehicle. They could go on to a landing. But these nerve-wracking interruptions had come at a time when the crewmen should have been looking for a suitable spot to sit down, rather than watching cabin displays. They had reached “high gate” in the trajectory - in old aircraft-pilot parlance the beginning of the approach to an airport in a landing path - where the Eagle tilted slightly downward to give them a view of the moon. When they reached “low gate” - the point for making a visual assessment of the landing site to select either automatic or manual control - they were still clearing alarms and watching instruments. By the time they had a chance to look outside, only 600 meters and three minutes’ time separated them from the lunar surface.

Armstrong saw the landing site immediately. He also saw that the touchdown would be just short of a large rocky crater with boulders, some as large as five meters in diameter, scattered over a wide area. If he could land just in front of that spot, he thought, they might find the area of some scientific interest. But the thought was fleeting; such a landing would be impossible. So he pitched the lander over and fired the engine with the flight path rather than against it. Flying across the boulder field, Armstrong soon found a relatively smooth area, lying between some sizable craters and another field of boulders.

How was the descent fuel supply? Armstrong asked Aldrin. But the lunar module pilot was too busy watching the computer to answer. Then lunar dust was a problem. Thirty meters above the surface, a semitransparent sheet was kicked up that nearly obscured the surface. The lower they dropped, the worse it was. Armstrong had no trouble telling altitude, as Aldrin was calling out the figures almost meter by meter, but he found judging lateral and downrange speeds difficult. He gauged these measurements as well as he could by picking out large rocks and watching them closely through the lunar dust sheet.

Ten meters above the surface, the lander started slipping to the left and rear. Armstrong, working with the controls, had apparently tilted the lander so the engine was firing against the flight path. With the velocity as low as it was at the time, the lander began to move backward. With no rear window to help him avoid obstacles behind the lander, he could not set the vehicle down and risk landing on the rim of a crater. He was able to shift the angle of the lunar module and stop the backward movement, but he could not eliminate the drift to the left. He was reluctant to slow the descent rate any further, but the figures Aldrin kept ticking off told him they were almost out of fuel. Armstrong was concentrating so hard on flying the lunar module that he was unable to perceive the first touch on the moon nor did he hear Aldrin call out “contact light,” when the probes below the footpads brushed the surface. The lander settled gently down, like a helicopter, and Armstrong cut off the engine.

4 days, 6 hours, 45 minutes, 57 seconds. CapCom: We copy you down, Eagle.

Armstrong: Houston, Tranquility Base here. THE EAGLE HAS LANDED.

CapCom: Roger, Tranquility. We copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.

And Armstrong started breathing again, too. He was not pleased with his piloting, but landing on the moon was much trickier than on the earth. He related the maneuver to his past experience in touching down during a ground fog, except that the moon dust had movement and that had interfered with his ability to judge the direction in which his craft was moving. Aldrin thought it “a very smooth touchdown,” and said so at the time. They were tilted at an angle of 4.5 degrees from the vertical and turned 13 degrees to the left of the flight path trajectory. Armstrong agreed that their position was satisfactory for lighting angles and visibility. At first, a tan haze surrounded them; then rocks and bumps appeared. Man had landed successfully on the moon - and on his first attempt.9

On the Surface

CapCom Charles Duke (Houston): “Good show.” Command module pilot Michael Collins (Columbia): “I heard the whole thing.” Commander Neil Armstrong (Eagle): “Thank you. Just keep that orbiting base ready for us up there.” This three-way conversation was the first of a kind, coming from two ground stations (one on the earth, the other on the moon) and a craft in lunar orbit. When Armstrong stepped out on the surface, he and Aldrin would turn it into a four-way talk, using their backpack radios.

Flight control told lunar launch team Armstrong and Aldrin to begin the two-hour practice countdown. The duo liked working in the one-sixth gravity; it made the tasks seem light. And the checkout went well - the thruster fuel was only ten percent less than they had expected; but a mission timing clock had stopped, displaying a ridiculous figure that they could not correlate to any point in the mission. They tried to turn it back on. When they could not, they left it alone to give the instrument a chance to recover; flight control could keep track of the time in the interim. It soon became apparent that they were going to be able to stay on the moon and explore.

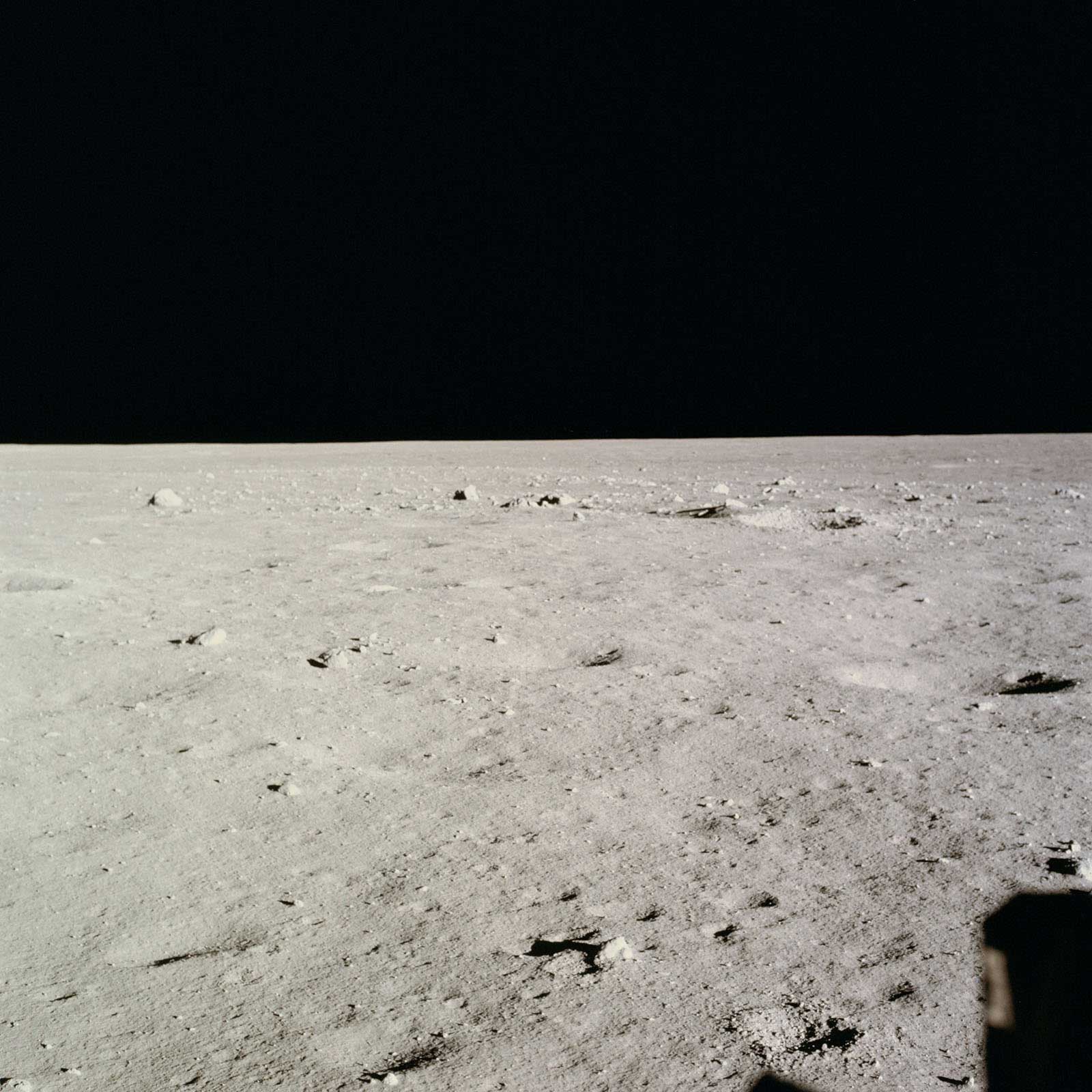

They wondered about their exact location, glancing out the windows and describing what they saw to give flight control and Collins some clues to aid in the search. While waiting to be found, Armstrong relayed all that he could remember about the landing. They knew they were at least six kilometers beyond the target point, although still within the planned ellipse. Colors were almost the same on the surface as from orbit: white, ashen gray, brown, tan, depending on the sun angle. Armstrong noticed that the engine exhaust had apparently fractured some of the nearby boulders. He glanced upward through the rendezvous window and saw the earth looming above them. They also heard via radio some unpleasant sounds from that planet, almost as though someone were moving furniture around in the back room. Flight control quickly silenced the racket, and the checkout on the moon continued.

Because they had adapted so easily to the one-sixth-g environment and because the simulated launch countdown had so few problems, Commander Armstrong decided to begin the extravehicular activity before the scheduled rest period. As Slayton had suspected, the astronauts could not just sit there. They wanted to get out and explore. Flight control agreed, adding that their movements would be watched on prime time television. Rigging up for the stroll took longer than during the training exercises on the earth, not because anything was wrong but because they took extra care to make sure that everything was right. About the only surprise they had was the discovery of a press-to-test button on the portable life support system that neither could identify. But they did not bother flight control about it; their backpack antennas were scraping the cabin ceiling, making communications scratchy, and they had more important things to talk about. They were quite comfortable with the life support systems on their backs, which pleased them after their experiences in the earth’s gravity. They did have to move carefully and methodically about the lander, however.

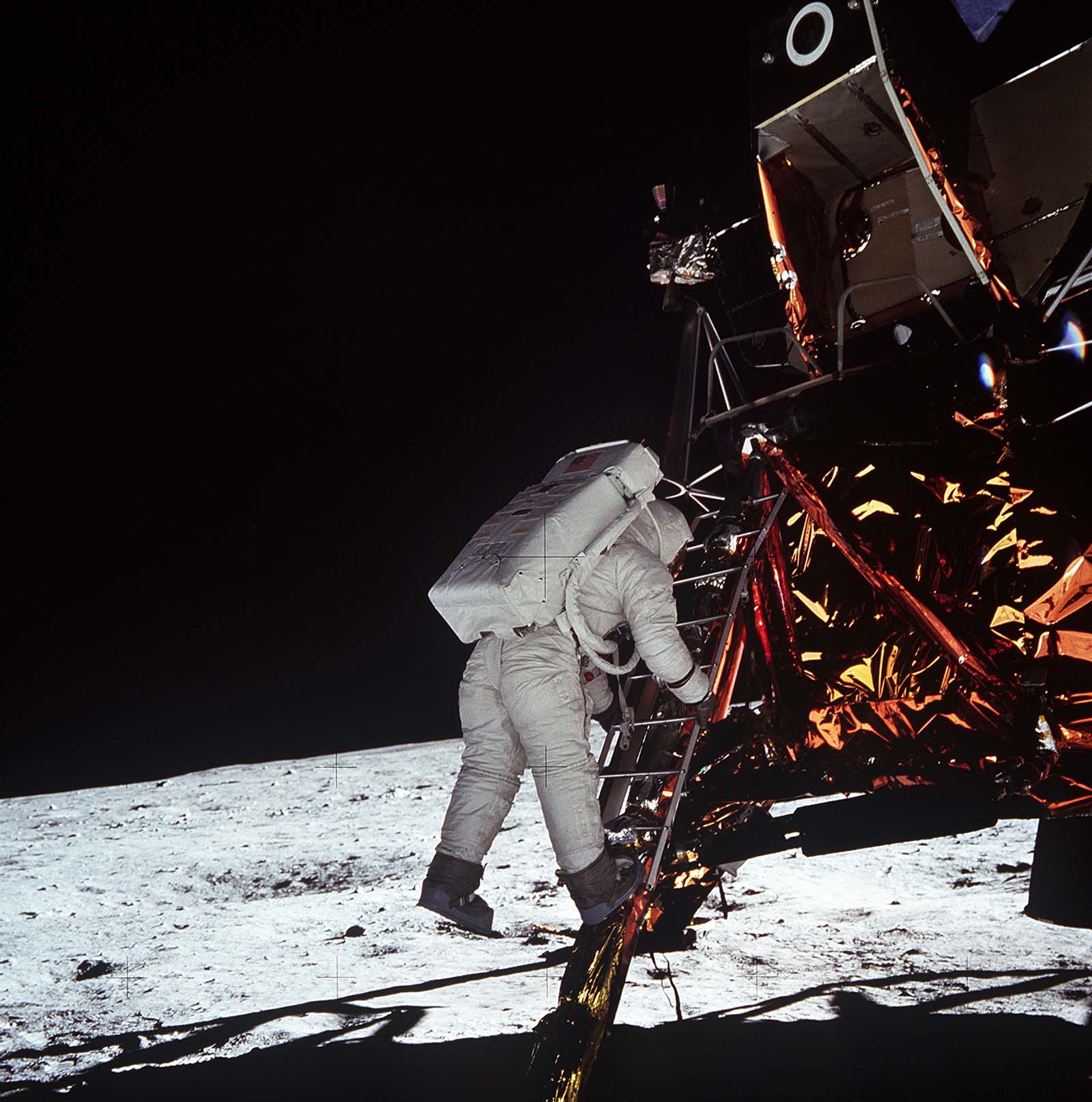

Finally, it was time to depressurize the cabin, open the hatch, and prepare to step out on the moon. Armstrong was wondering if the light would be good enough for the television camera to capture his first step, and he was thinking about the gymnastics of backing through the hatch and standing on the porch. Forty-five minutes after flight control had given the crew a go for depressurization, the cabin had still not quite reached a zero reading on the gauges, but it was close. The crewmen could not wait any longer; 6 hours and 21 minutes after landing, 20 July, they pulled the hatch open, and Aldrin watched carefully as Armstrong backed out. When he came too close to the sides of the hatch with his bulky backpack, Aldrin gave him detailed instructions - a little to the right, now more to the left - until he had safely reached the porch. Armstrong turned a handle to release the latch on the experiments’ compartment and then went down as far as the footpad. He checked to see if he could get back up - that first rung was high. He did not expect any problems, although it would take a pretty good jump. Then the watching world saw what it had been waiting for - Armstrong’s first step onto the moon.

“That’s one small step for [a]* man, one giant leap for mankind.”

With this historic moment behind him, Armstrong began to talk about the surface, about the powdery charcoal-like layers of dust, as he and the television camera looked at his bootprints in the lunar soil. One-sixth g was certainly pleasant, he said. He glanced up at the lunar module cabin, at Aldrin near the window. The lunar module pilot explained to the viewers what Armstrong was doing as he gathered the contingency sample and worked it into the pocket on his suit leg. Armstrong described the stark beauty of the moon, likening the area to the high desert country in the United States.

When Aldrin asked, “Are you ready for me to come out?” Armstrong answered, “Yes.” The commander realized that extravehicular activity on the moon was a two-man job at the minimum. From his position on the ground, he could not give Aldrin as much help in clearing the hatch as he would like, but he did the best he could. On reaching the porch, Aldrin commented on how roomy it was; there was no danger of falling off. “I want to . . . partially close the hatch, . . . making sure not to lock it on my way out.” Eighteen minutes and twelve seconds after the first man stepped on the moon, he was joined by his companion. Aldrin also was struck by the “magnificent desolation.” Although he could move easily, with no hindrance from the big backpack, he noticed that he did have to think about the position of the mass. Aldrin and Armstrong loped along, tried a kangaroo hop, and reverted to the more conventional mode of simply putting one foot in front of the other.** Despite the ease of movement, both explorers believed that hikes of two kilometers or more would be tiring. On the earth, they had to think only one or two steps ahead; on the moon, they had to work out five to six steps in advance. And the rocky soil was slippery.

In some ways, the astronauts felt frustrated on this first lunar outing; there was so much to see and do and so little time. They had planned some of their moves as they looked out the window before disembarking, but their field of view was limited to 60 percent of the area. This first landing may have been in what was supposedly a nondescript region of the moon, but even here they hoped that the cameras were capturing some of the detail they did not have an opportunity to investigate personally. Not being able to get down on their hands and knees to examine items closely annoyed them; but the powdery soil, its tendency to adhere to their clothing, and the difficulty of regaining upright positions in the bulky space suits dissuaded them from trying to kneel.

Shortly after Aldrin alighted, Armstrong unveiled the plaque on the leg of the LM, described the representation of the earth’s two hemispheres, and read the words to a vast listening audience:

Here Man from the planet Earth first set foot upon the Moon, July 1969 A.D. We came in peace for all mankind.

Underneath were the crew members’ signatures and the signature of the President of the United States (Nixon).

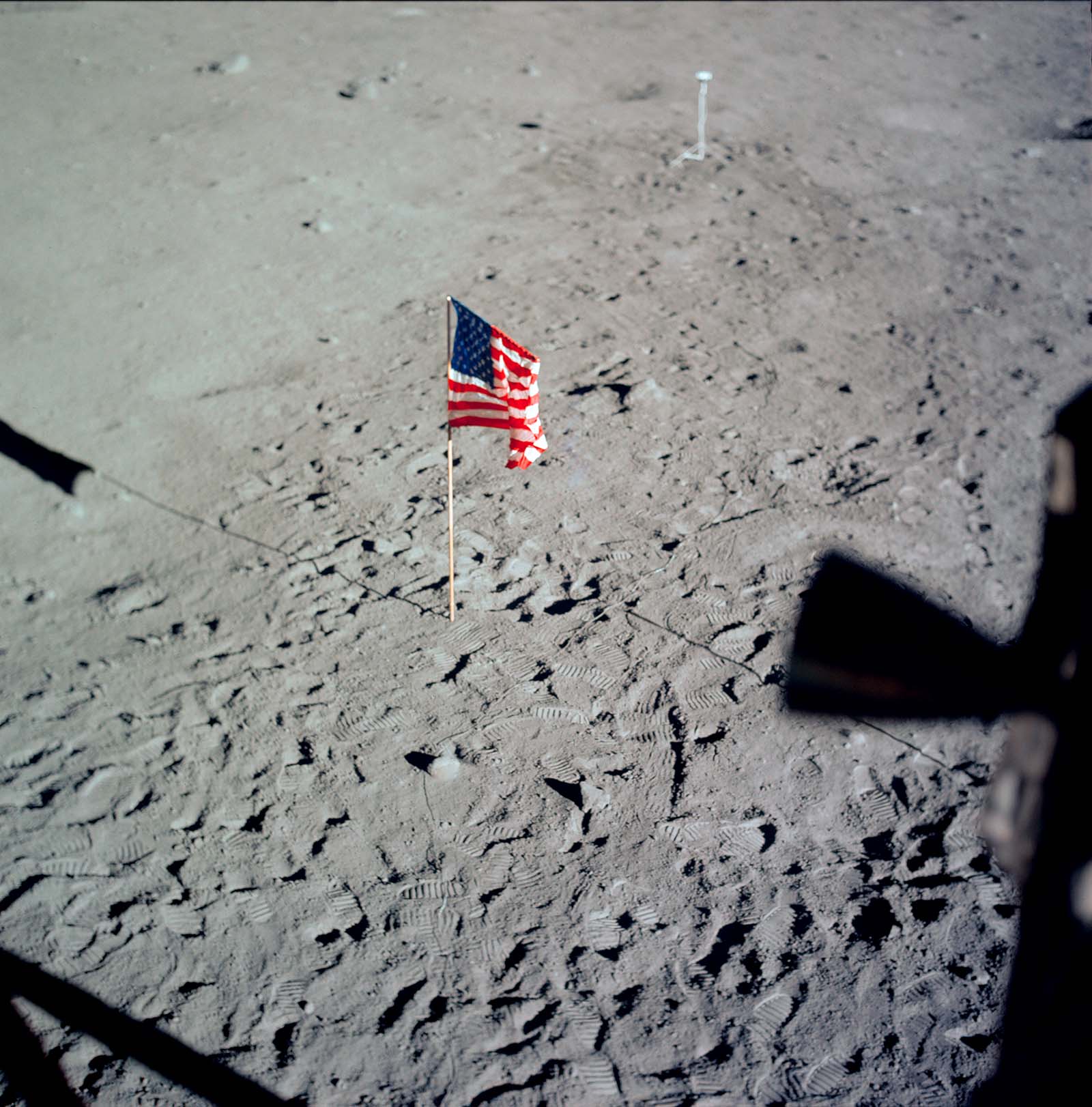

A little later they held the flag-raising ceremony. The telescoping flagpole stuck and they could not pull it out to its full extent; afraid that they might lose their balance and fall on the rocky surface, they did not try very hard. The ground below the surface was very hard, and they pushed the pole in only 15 to 20 centimeters. Flight control told Collins, circling in the command module above, of the ceremony, remarking that he was probably the only person around without television coverage of the event.

After another brief stint of evaluating their ability to move around, the crewmen were asked to step in front of the camera so the President could speak to them. President Nixon said, “I am talking to you by telephone from the Oval Room at the White House, and this certainly has to be the most historic telephone call ever made.” The President said America was proud of them and their feat had made the heavens a part of man’s world. Hearing them talk from the moon inspired a redoubling of effort “to bring peace and tranquility to Earth. . . . For one priceless moment in the whole history of man, all the people on this Earth are truly one; one in their pride in what you have done, and one in our prayers that you will return safely to Earth.”

All of the ceremonial episodes were short, the President’s call was the last, and none used very much of the precious 2 hours and 40 minutes of the schedule.

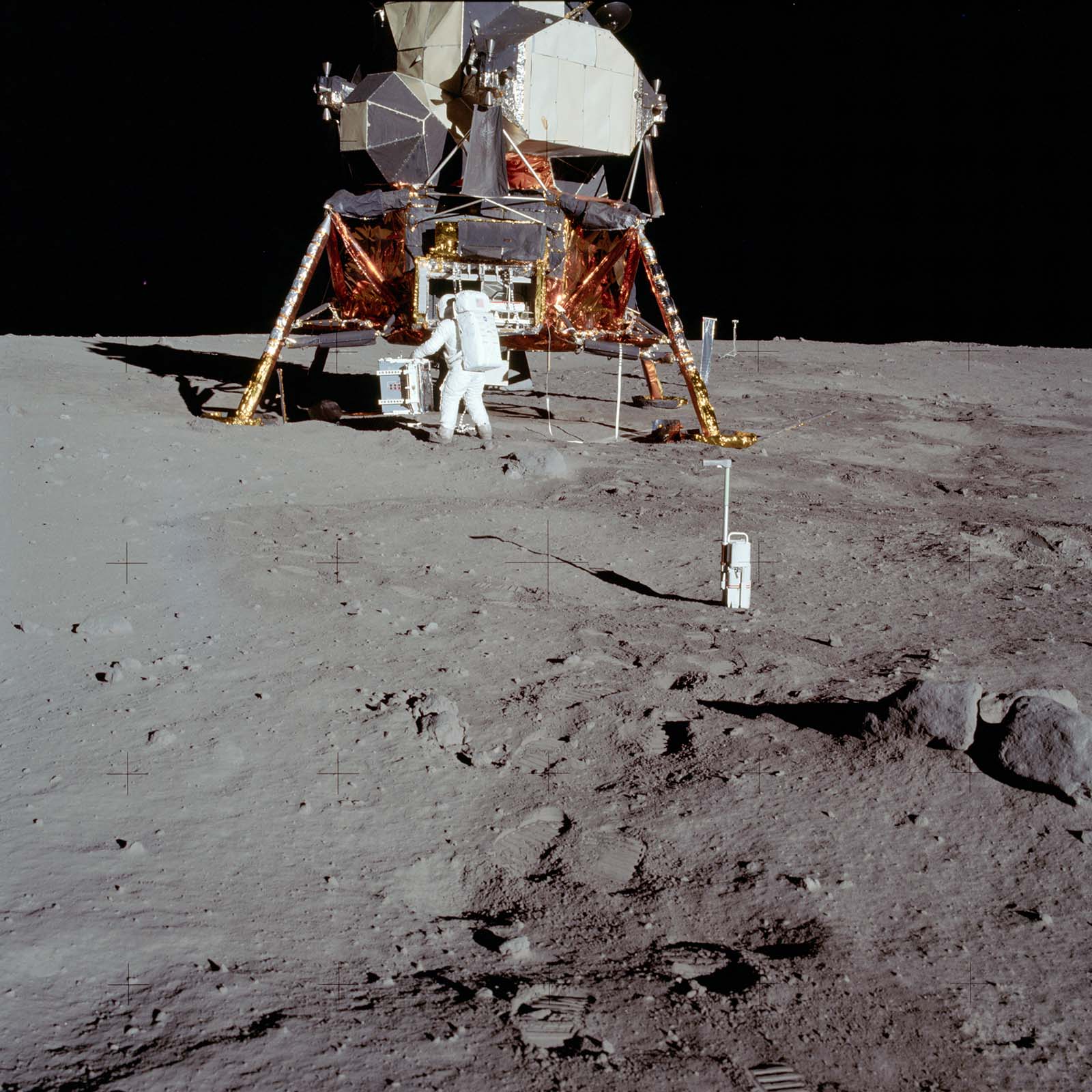

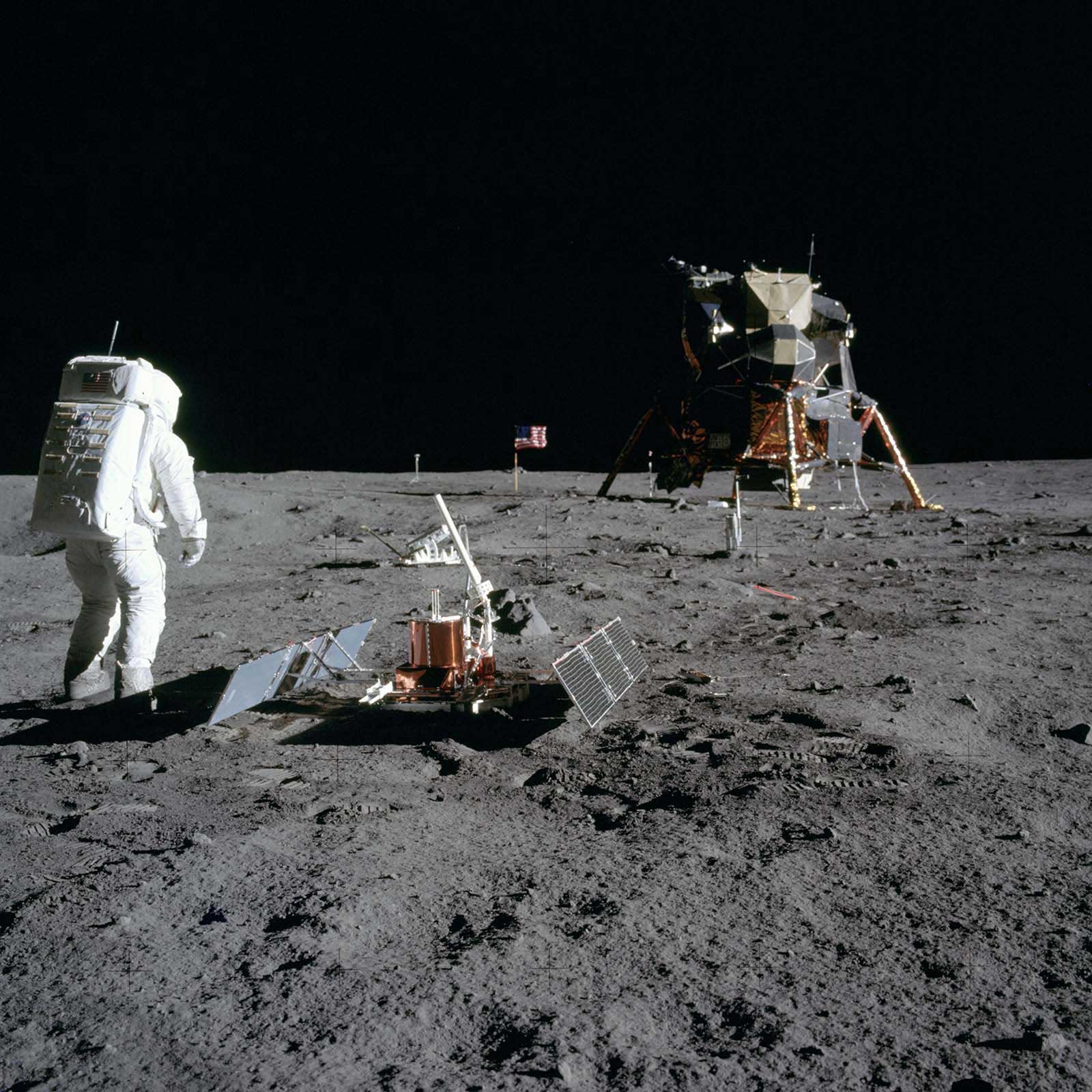

The astronauts began the scientific part of their mission (see appendix D for experiment descriptions). Getting the science package from its stowage area was easier than in training and, although the kit had been close to the descent engine, no heat damage was observed. Aldrin elected to deploy the experiments manually and looked for level spots in which to set them up. He soon found that it was difficult to decide what was level ground by just looking at the surface. The laser reflector had a leveling device - a bubble, or “BB” - but Aldrin had trouble centering it. He finally gave up and went on to other tasks. Armstrong came over later to photograph the reflector, and the bubble was on dead center. They had no explanation for this. The commander wished he had some kind of a rock table on which to set the packages, to keep them from settling into the lunar soil, but there was no time for that kind of refinement. Aldrin set up the solar array experiment; one panel popped up automatically, but he had to pull on a lanyard with his gloved hand to get the other in place.

Time was getting short, so Aldrin left the experiments and began collecting the documented samples. Reminded by flight control that scientists wanted two core-tube specimens, he pushed the tube about 10 centimeters into the ground and began tapping it with a hammer. When it did not go much farther, he beat on it until the hammer made dents in the top of the tube. Even then he could only get it about five centimeters deeper. He pulled the sampler out of the ground, meeting little resistance. He had an impression of moisture in the soil, because of the way the material adhered to the tube. He tried again about five meters away, but the results were not much better. During the rapping and tapping, the seismic package transmitted the vibrations back to the earth.

Armstrong had been snapping pictures and filling sample boxes with lunar rocks and surface soil, describing what he was doing as he went from place to place. It took longer to gather the bulk samples than it had during earth simulations. He tried to keep as far from the engine exhaust blast area as he could. He operated the stereoscopic camera developed by scientist Thomas Gold, even though the trigger was difficult to pull with his gloves on. Once he wandered out about 100 meters, being careful not to get out of sight of the lander, to look at a crater and take some pictures. The trip took only a few minutes and was easy, but when he returned he wanted to stop and rest. Then he had to close the sample boxes, which took more effort than he had expected.

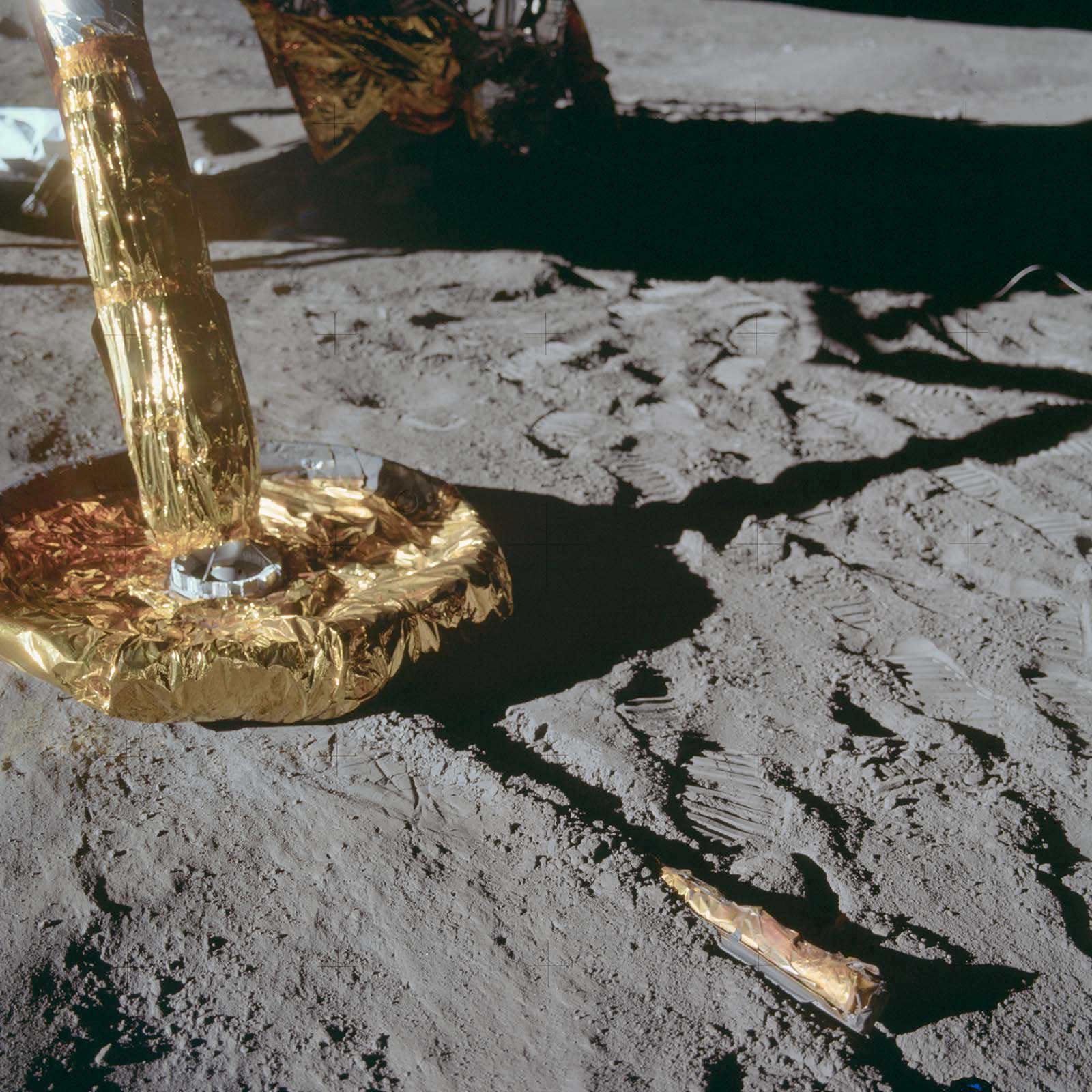

All during the exercise, the consumables were adequate, and flight control extended the time on the surface by 15 minutes. But, still too soon, CapCom McCandless finally had to tell Aldrin he would have to head back for the cabin in 10 minutes. The lunar module had withstood the landing well. It had apparently been a very soft landing, because the footpads Had sunk only about five centimeters into the soil. The pilots found little wrong with their machine except some broken thermal insulation (the gold foil) on the lander’s legs.

After an hour and three-quarters on the surface, Aldrin heard McCandless say, “Head on up the ladder, Buzz.” The first step was a long one, and the soil on the soles of his boots made the rungs slippery, but he made it. Using the pulley, the crew hauled the sample boxes and cameras back into the cabin. Armstrong did a deep knee bend and jumped straight up, almost two meters, to the third rung of the ladder. Neither crewman had any trouble getting into the cabin. Once inside, they threw out a number of items that were just taking up space. For the most part, the crew was out of touch with the earth at this time, because the backpack antennas were again scratching against the ceiling. Flight control told Collins that the lunar walkers had returned to their ship, and he shouted, “Hallelujah.”

Armstrong and Aldrin found the post-EVA check easier than the preparations for getting out, but there was a long checklist to work through. They were glad they had tossed out some of the equipment, because there was still a “truckload” in the cabin. They ate during this period, but made no real attempt to relax, let alone sleep. They knew they could not sleep if all the launch preparations were not finished. They wondered how Collins was faring, racing around upstairs getting ready for the rendezvous.

Once they had finished their chores and were ready to call it a night, flight control began a question-and-answer session on the lunar surface operations. This came after they had already said “good night” twice. When the questions began to require extensive answers, especially on geology, Aldrin asked Houston to postpone the discussion until later. Flight control agreed, and Owen Garriott (now at the capcom console) said he hoped this transmission would be the final good night.

Armstrong and Aldrin found their lunar house dirty, noisy, crowded, and too brightly lit. They put on their helmets to keep from breathing the dust, to muffle the racket, and to protect themselves in any unexpected cabin depressurization. Shutting out the light was not so easy. The shades over the windows were little more than transparent sheets; even the lunar horizon could be seen through them. When Armstrong noticed that the light seemed to be getting stronger, he opened his eyes to find that the earth was pouring its rays through the sextant.

Getting to sleep proved to be a constant battle, and neither pilot was sure that he ever completely dozed off. Aldrin was on the floor, and Armstrong was on the ascent engine cover with his legs in a sling he had rigged up from a tether. Neither was uncomfortable at first - the suits were no problem (“You have your own little snug sleeping bag,” Aldrin said) - but soon they began feeling cold. After a time, and much fiddling with the controls, they were warmer, but they told Houston that future moon pilots should adjust the cabin temperature before they started to rest.

While his crewmates had been active on the surface, Collins had been busy in the command module. There was not much navigating to do, so he took pictures and looked out the window, trying to find the lunar module. He never found it; neither did flight control. There was just too much real estate down there to be able to search the whole area properly. Collins divided the part of the moon he was flying over into segments, but he had no better luck. Armstrong and Aldrin had taken the 26-power monocular with them, but Collins did not think it would have helped much, anyway. He did complain that all this searching cut into the time he needed for taking pictures on each circuit, but he was philosophical about it. As he said, “When the LM is on the surface, the command module should act like a good child and be seen and not heard.”10

- Whether he actually uttered the article or not later caused considerable discussion. Armstrong, himself, later wrote: “I thought it had been included. Although it is technically possible that the VOX didn’t pick it up and transmit it, my listening to the recording indicates it is more likely that it was just omitted.”

- Armstrong even tried jumping straight up. When he noticed a tendency to pitch backward, he stopped.

Return from Tranquility

After their fitful rest period, the moon dwellers were roused by Houston and told to get ready to leave. Flight control and the crew discussed the most probable location of the lunar module, and Armstrong and Aldrin then aligned the guidance platform by the moon’s gravity field. They had some difficulty finding enough stars to sight on, but the Eagle was ready to take off on 21 July - 21 hours 36 minutes after landing and more than 124 hours after leaving the earth on 16 July. Up above, Collins had been alone since the 13th revolution, and he did not expect to have company until the 27th circuit, 28 hours after the lander had separated from the command module. As the time drew nearer for ignition of the ascent engine, Collins positioned his ship so its radar transponder would be pointing in the direction of the lunar module radar signal. Everything was ready for the next critical move.

The Eagle lifted off the moon exactly on time, soaring straight up for 10 seconds to clear its launch platform (the descent stage) and the surrounding ground obstacles. When its speed reached 12 meters per second, it pitched over into a 50-degree climbing angle. Armstrong and Aldrin heard the pyrotechnics fire and saw “a fair amount of debris” when they first detected motion. The onset of this velocity was absolutely smooth, and they had difficulty sensing the acceleration. But when the cabin tilted over and they could see the lunar surface, they realized that they were going fast. On several occasions, familiar landmarks indicated they were on a correct flight path - Armstrong spoke of one named “Cat’s Paw” and Aldrin spotted “Ritter” and “Schmidt.”

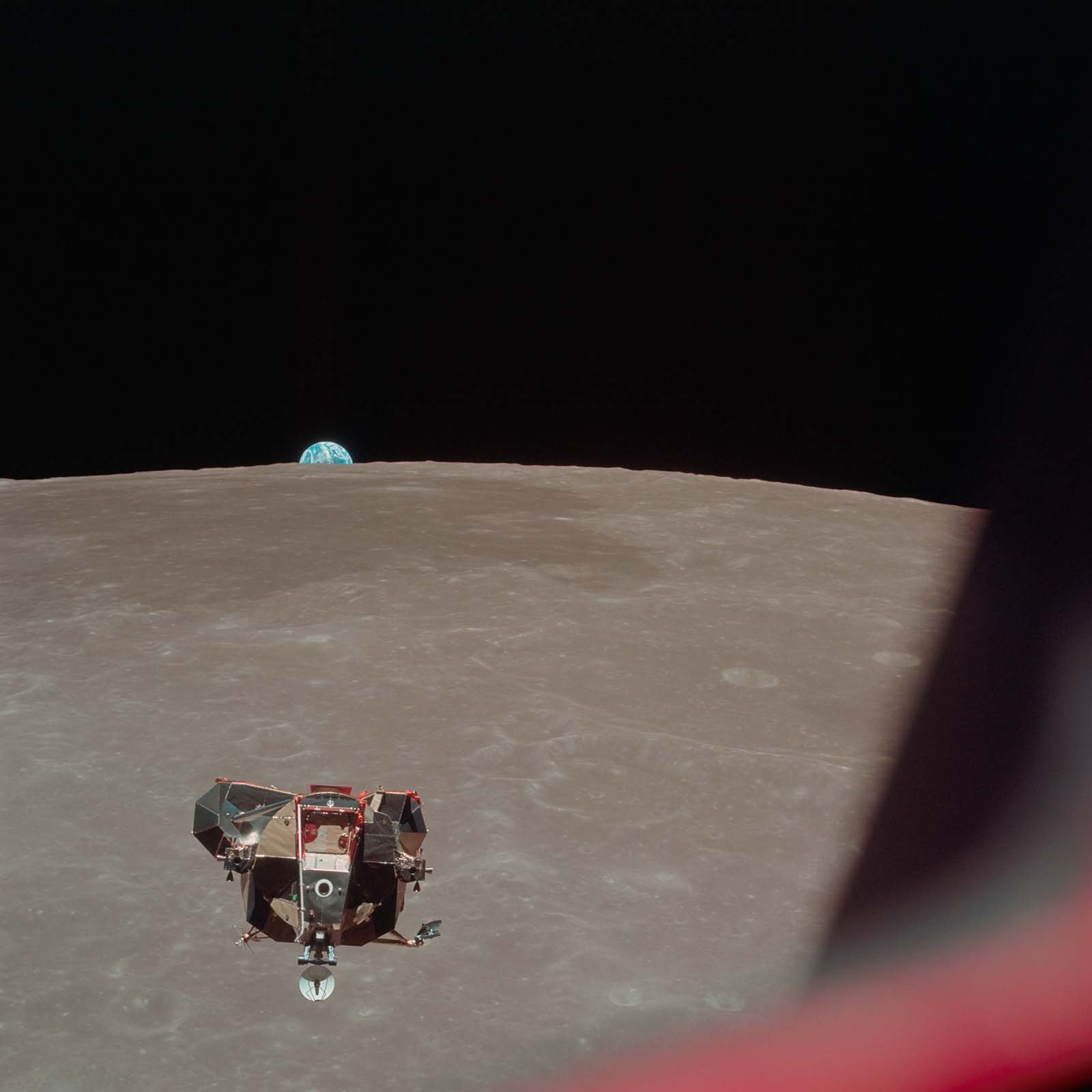

Stafford and Cernan had told Armstrong about their lander’s lazy, wallowing “Dutch roll,” and the Eagle was flying the same way. When the engine had fired for seven minutes, the lunar module had reached an elliptical orbit of 17 by 84 kilometers, and the race to catch the mother ship was on. Another hurdle had been successfully vaulted. Collins could now call on one of the 18 recipes in his rendezvous cookbook to rescue the lander if necessary. An hour after the ascent engine’s first firing, Armstrong turned it on again, to kick the low point of the path up to 85 kilometers, to a nearly circular orbit. After checking the results with flight control, as well as with Armstrong and Aldrin, Collins found that the lander was on a good flight path. He could let orbital mechanics take over and wait until Armstrong slowed the lander’s catchup speed at the proper moment.

Eventually, Collins told his crewmates to turn off their tracking light; he could see them fine without it. Later, as the lander turned the lunar corner and lost contact with the earth, Armstrong slowed his vehicle for stationkeeping 30 meters from the command module, so Collins could inspect the lander before docking. During the inspection, Collins asked his shipmates to roll over a bit more, and they went straight into gimbal lock. Armstrong blamed himself for “the goof,” but it posed no real problems. Like all the lunar modules, the Eagle was a sporty machine once it was rid of its descent stage and much of its ascent engine fuel, and it took skill to keep the skittish bird from dancing about. Four hours after lunar launch, the two vehicles were ready to dock.

Collins rammed the probe dead center into the lander’s drogue. With the ascent stage fuel tanks nearly empty, he met with little resistance; it felt almost as though he was shoving the command module into a sheet of paper. He had to look out the window to make sure they were docked. Then he pressed the switch to reel the lander in closer and secure it with the capture latches. Suddenly there was a big gyration in yaw - perhaps because of the retraction, perhaps because of a lunar module thruster that seemed to be firing directly at the command ship. Collins used his handcontroller to steady the vehicles. Just as he was wondering if he would have to cut loose and try again, Columbia grabbed the Eagle and held on.

Collins hurried to get the hatch and probe out of the way, to greet his returning companions. As he did, the same strong smell of burnt electrical insulation met his nostrils. But, again, nothing seemed to be wrong. Armstrong and Aldrin began vacuuming the lunar dust from themselves, their equipment, and the sample boxes. The dust did not bother the trio much, and they began unloading, cleaning, and stowing. Their progress was so good that flight control considered bringing them home one revolution earlier than the planned 31st circuit (one less than the Stafford crew had traveled). But they decided against it.

During the 28th orbit, Armstrong reported the crew safely aboard the command ship. Flight control soon signaled the lander to remain near the moon until its orbit decayed and it crashed on the surface. The Eagle flew slowly away, its thrusters firing to maintain attitude. Aldrin thought he saw some cracks in its skin, but Houston told him that cabin pressure was steady. That had been one very good bird.

Now the crew had nothing to do but rest, eat, take pictures, and wait to begin the return to earth. Collins did wrestle with some command module attitude excursions but, once the big service module engine fired behind the moon, the ship steadied, right on course. The firing lasted so long that Collins wondered if the automatic turnoff was going to work. Just as he reached for the switch, the engine stopped. After the crew had checked the results, all they could do was ride their stable machine home. Armstrong asked when they would acquire the flight control signal, and Aldrin, now totally relaxed, answered that he did not have “the foggiest” notion. Soon the commander wanted to know if anyone had any choice greetings when they did talk to Houston, but no one volunteered. Aldrin readied a camera to photograph the earthrise. Coming around the corner, Collins called to CapCom Duke, “Time to open up the LRL doors, Charlie.”

Now they “mostly just waited,” as Collins later said. Flight control passed up the usual newscast, telling them that only four nations* in the world had not told their citizens about the flight. President Nixon, in his White-House-to-Moon chat, had mentioned that he would meet them on the Hornet; now they learned that he was sending them on a world tour. After more news - about Vietnam, the Middle East, oil depletion allowances, and a drop in the Dow industrial averages - the astronauts knew they had truly returned from Tranquility.

On television they, like the Borman and Stafford crews before them, philosophized about the significance of their voyage. Armstrong spoke of the Jules Verne novel about a trip to the moon a hundred years earlier, underscoring man’s determination to venture out into the unknown and to discover its secrets. Collins talked of the technical intricacies of the mission hardware, praising the people who had made it all work. Aldrin spoke about what the flight meant to mankind in striving to explore his universe and in seeking to promote peace on his own planet. Armstrong closed the session, speaking of Apollo’s growth from an idea into reality and ending with, “God bless you. Good night from Apollo 11.”

The pilots watched the earth grow larger and larger. They televised more of life in a spacecraft. A day before landing, they checked out the command module entry monitoring system, so flight control could check for “any funnies,” as Collins called them. But there did not appear to be any. Stowage went smoothly. After they turned the ship into the reentry position and kicked off the service module, they saw it sail by, carrying with it the engine that had served them so well.

As they neared the earth, Houston began grumbling about the weather in the target zone - thunderstorms and poor visibility. Finally the landing point was moved. Collins was not very happy about trying to reach a spot 580 kilometers farther downrange than he had trained for. He did not complain, but he worried some.

When the command module hit the reentry zone, Aldrin triggered a camera to capture on film, as best he could, the colors around the plasma sheath - lavenders, little touches of violet, and great variations of blues and greens wrapped around an orange-yellow core. A surprisingly small amount of material seemed to be flaking off the spacecraft; Collins did not see the chunks he had seen in Gemini.

By now, the crew had turned the spacecraft over to its computer - that fourth crew member who had done a lot of the mission flying to this point - and were watching the entry monitor. The computer held on to a small downrange error for a while, decided it was wrong, and dumped the figure. The vehicle dipped down into the atmospheric layer, zipped up in a roller coaster curve out of the layer, and then came screaming back in. The drogue parachutes opened, and the ship steadied. Armstrong and his crew felt the jerk as the main parachutes came out; it seemed to take a long time for those three parachutes to blossom. Some good sounds came up from below as they heard the recovery forces trying to talk to them at the end of the reentry communications blackout. Reentry was fairly comfortable for the crewmen, without their bulky suits, but splashdown came with a jolt - 24 June 1969 - 8 days, 3 hours, 18 minutes, 18 seconds after leaving Cape Kennedy.**

Columbia landed close to its reprogrammed target and flipped over on its nose in the water, but a flick of a switch inflated the air bags and it soon turned upright. None of the crew were seasick, but they had taken preventive medication before the landing. They went through a lengthy checklist of the things to be done to keep the world free from contamination. It had been a long trip.

A swimmer threw them the biological isolation garments, and they put them on. Armstrong disembarked first, followed by Collins and then Aldrin. As they passed through the hatch they inflated their water-wing life preservers before jumping into the raft. Armstrong noticed that a swimmer was having trouble closing the hatch; he went over to help - the commander did not want anything to happen to “those million dollar rocks.” He had trouble, too, so Collins came back and adjusted the handle; then they closed the door.

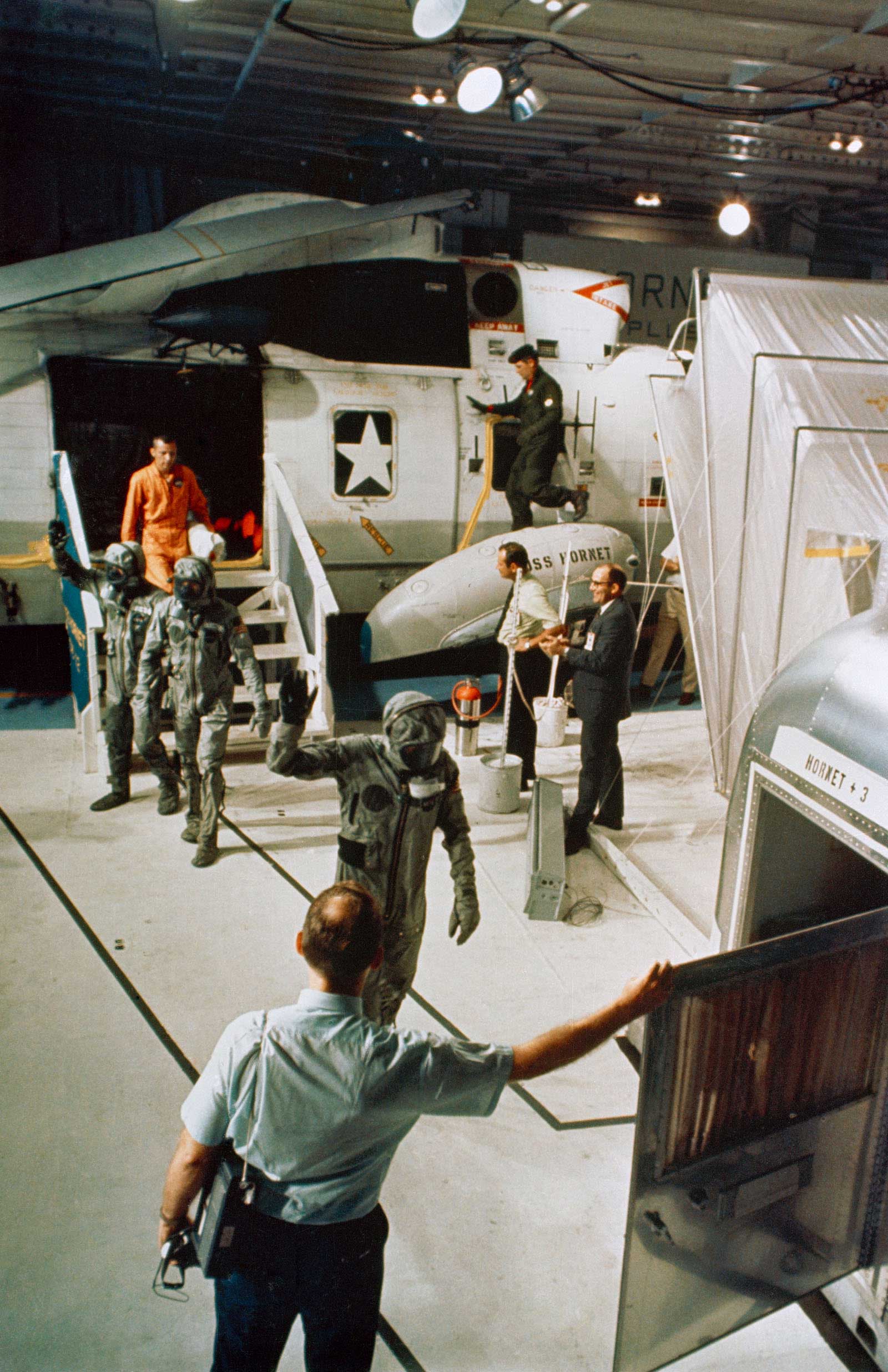

In the rubber boat, the astronauts were scrubbed down with an iodine solution by the swimmers; they, in turn, did the same for the frogmen. While a helicopter lifted the crew to the U.S.S. Hornet, the spacecraft got its scrubdown before it, too, was lifted to the ship. The travelers stepped from the aircraft onto the carrier deck and straight into the mobile isolation unit. The “national objective of landing men on the moon and returning them safely to earth before the end of the decade” had been achieved.

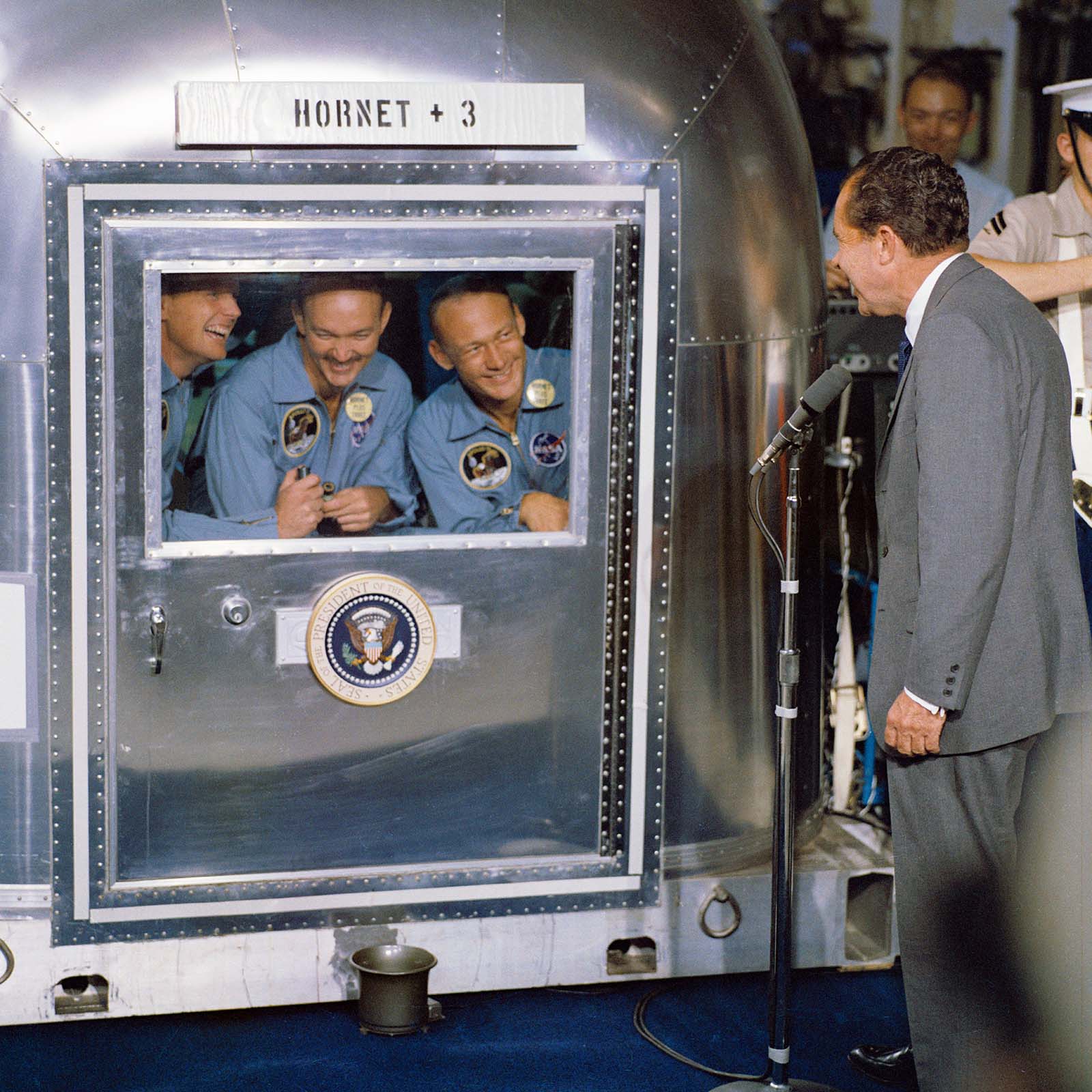

But the safe recovery was not the end of activities for Apollo 11. First, the crewmen changed from the isolation garments to more comfortable flight suits and crowded to the door where, behind glass, they presented their now familiar countenances (although Collins had grown a moustache that altered his looks) to the TV cameras. Years of study of the lunar samples lay ahead, and the crew had to spend their 21 days in quarantine. During that period, they answered a formidable set of questions about everything that had taken place, relying on both notes and memory, to make sure that they had done all they could to assist the crews that would follow them to the moon. Collins closed these thorough and exhaustive sessions by saying, emphatically, “I want out.”

When they did get out, there was the swirl of a world tour; men and women from all walks of life, of varying colors, creeds, and political persuasions, both young and old, hailed the feat of mankind’s representatives. “For one priceless moment . . . .”11

- China, Albania, North Korea, and North Vietnam.

- According to the command module computer, Columbia landed at 13 degrees 19' north latitude and 169 degrees 9' west longitude.

ENDNOTES

- J. B. Hustler and T. J. Lauroesch, “Final Report, Phase IV: Lunar Photo Study, . . . 30 November 1967-30 November 1968,” Eastman Kodak Co. rept., 14 March 1969, pp. iii-v; John R. Sevier, telephone interview, 7 June 1971; Arthur T. Strickland memo, “Apollo Lunar Landing Site Designation,” 23 Dec. 1968, with enc., Lee R. Scherer to Apollo Prog. Dir., “Clarification of Nomenclature of Apollo Lunar Landing Sites,” 5 Dec. 1968.X

- 10:56:20 PM, EDT, 7/20/69: The Historic Conquest of the Moon as Reported to the American People by CBS News over the CBS Television Network (New York: CBS, 1970; this book, under 200 pages, provides an excellent cross-section of activities around the world as related to Apollo 11 events of 16 through 24 July 1969), pp. 13, 15, 20; Charles D. Benson and William Barnaby Faherty, Moonport: A History of Apollo Launch Facilities and Operations, NASA SP-4204 (Washington, 1978), p. 474; MSC, “Apollo 11 Mission Commentary,” 16 July 1969, tapes 3-1, 4-1; MSC News Center, Apollo 11 Accreditation List [16 July 1969].X

- Michael Collins, Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut’s Journeys (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 1974), pp. 355-59; “Apollo 11 Mission Commentary,” tape 11-2; MSC, “Apollo 11 Technical Crew Debriefing,” 2 vols., 31 July 1969, vol. 1, p. 1-3; Collins to James M. Grimwood, 13 Dec. 1976, with enc.X

- NASA, Mission Report: Apollo 11, MR-5 (Washington, 14 Aug. 1969), p. 5; George H. Hage memo, “Mission Director’s Summary Report, Apollo 11,” 24 July 1969; MSC, “Apollo 11 Technical Air-to-Ground Voice Transmission (GOSS Net 1),” July 1969, p. 17; “Apollo 11 Debriefing,” 1: 3-1, 3-2, 3-4, 3-8, 3-9, 3-11, 3-12; Christopher C. Kraft, Jr., memo, “Flight Control Manning for Apollo 11,” 30 June 1969, with enc.; John P. Mayer memo, “SSR Manning for Apollo 11,” 14 July 1969, with enc.; NASA, “Apollo 11 Lunar Landing Mission,” press kit, news release 69-83K, 26 June 1969, pp. 197-99; Clifford E. Charlesworth et al., “Flight Directors Report, Apollo 11,” n.d., p. 3; Collins letter, 13 Dec. 1976.X

- “Apollo 11 Voice,” p. 16; MSC, “Apollo 11 Onboard Voice Transcription, Recorded on the Command Module Onboard Recorder Data Storage Equipment (DSE),” August 1969, pp. 19, 32, 35, 38-40, 42; “Apollo 11 Debriefing,” 1: 3-10, 4-4, 4-5, 6-32, 6-33; MSC, “Apollo 11 Mission Report,” MSC-00171, November 1969, pp. 1-1, 3-1, 4-1, 7-1.X

- “Onboard Voice,” pp. 43, 46-50; “Apollo 11 Voice,” pp. 9, 24, 30, 34, 50, 52, 66, 96, 101, 106-112, 147, 154; Charlesworth et al., “Flight Directors Report,” pp. 3-7; Hage memo, “Apollo 11 Daily Operations Report No. 2,” 18 July 1969; Hage memo, 24 July 1969; “Apollo 11 Debriefing,” 1: 5-5, 5-6, 5-9, 6-19 through 6-22; 10:56:20 PM, EDT, 7/20/69, pp. 53-54.X

- Hage memo, “Apollo 11 Daily Operations Report No. 3,” 19 July 1969; Hage memo, 24 July 1969; Hage memo, “Apollo 11 Daily Operations Report No. 4,” 20 July 1969; Charlesworth et al., “Flight Directors Report,” pp. 9-14; “Mission Report,” pp. 3-1, 4-5, 4-6; “Apollo 11 Voice,” pp. 157, 166-69, 171, 174, 183, 198, 200, 204-05, 210-11, 217-18, 220, 224, 227, 233, 235-38, 247; “Apollo 11 Debriefing,” 1: 6-30, 6-31, 6-33 through 6-36, 7-13 through 7-18, 8-1; Collins, Carrying the Fire, pp. 339, 342; “Onboard Voice,” pp. 58, 64, 65, 71, 75-77, 85-86, 91, 93, 112, 119-20, 125, 130-31, 136; Collins to Grimwood, 13 Dec. 1976; Kenneth A. Young, telephone interview, 7 Dec. 1977.X

- Hage memos, 20 and 24 July 1969; Hage memo, “Apollo 11 Daily Operations Report No. 5,” 21 July 1969; Charlesworth et al., “Flight Directors Report,” pp. 12-14; “Apollo 11 Debriefing,” 1: 8-2, 8-5 through 8-7, 8-11, 8-15, 8-26, 8-28, 8-29, 8-31; “Mission Report,” pp. 3-1, 4-4 through 4-8; Mission Report: Apollo 11, p. 6; “Onboard Voice,” pp. 144, 147-49, 156, 158-59; “Apollo 11 Voice,” pp. 293-95, 298, 300-01, 306, 307; Neil A. Armstrong to JSC History Off., 3 Dec. 1976.X

- “Apollo 11 Debriefing,” 1: 9-1, 9-4, 9-6, 9-17 through 9-28; “Onboard Voice,” pp. 175-78; “Apollo 11 Voice,” pp. 308, 310, 312-17; Charlesworth et al., “Flight Directors Report,” pp. 14-16; Hage memos, 21 and 24 July 1969; “Apollo 11 Mission Report,” pp. 1-1, 3-1, 3-2, 4-8, 4-9, 5-4 through 5-6; Floyd V. Bennett, “Mission Planning for Lunar Module Descent and Ascent,” Apollo Experience Report, NASA Technical Note S-295 (MSC-04919), review copy, October 1971, pp. 3, 8; Mission Report: Apollo 11, p. 6; Armstrong to JSC History Off., 3 Dec. 1976.X

- “Apollo 11 Debriefing,” 1: 10-1, 10-6 through 10-68, 10-72 through 10-82, 11-1 through 11-6; “Apollo 11 Voice,” pp. 318-26, 331-36, 341-43, 352, 358-59, 368, 370-98, 400-11, 414, 422-30; Apollo 11 Mission Report,” pp. 1-1, 1-2, 3-2, 4-9 through 4-16, 5-7, 5-8, 9-1, 9-19, 9-33, 10-1 through 10-4, 11-1 through 11-5, 12-7; Mission Report: Apollo 11, pp. 2-5; Armstrong to JSC History Off., 3 Dec. 1976; Armstrong to Loyd S. Swenson, 2 Oct. 1975.X

- “Apollo 11 Debriefing,” 2: 11-3, 11-4, 11-6, 12-3 through 12-6, 12-10, 12-11, 12-14, 12-20 through 12-25, 12-32, 12-33, 12-38 through 12-43, 13-1 through 13-5, 14-1, 14-3, 14-5, 14-10 through 14-13, 15-1 through 15-7, 16-l through 16-7; “Onboard Voice,” pp. 158-59, 161, 175-80, 183-86, 189, 193-05, 207-10, 214-16, 218, 221-22, 225-26, 236-243, 247; “Apollo 11 Voice,” pp. 470, 480-82, 488-92, 496-99, 502, 516, 521, 523-35, 538, 543-47, 550, 554-57, 564, 570, 572, 574, 576, 583-88, 604, 608-10, 613-14, 623-24; Charlesworth et al., “Flight Directors Report,” pp. 18-25; “Mission Report,” pp. 1-2, 3-2, 3-4, 3-5, 4-16 through 4-20, 5-8 through 5-11, 7-4, 7-5; Apollo Program Summary Report, JSC-09423, April 1975 (published as NASA TM-X-68725, June 1975), p. 2-38; Hage memo, “Apollo 11 Daily Operations Report No. 6,” 22 July 1969; Hage memo, 24 July 1969; Mission Report: Apollo 11, pp. 5-7; Collins to Grimwood, 13 Dec. 1976; Armstrong to JSC History Off., 3 Dec. 1976; Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin, Jr., with Wayne Warga, Return to Earth (New York: Random House, 1973), p. 241.X