Contending Modes

1959 to Mid-1962

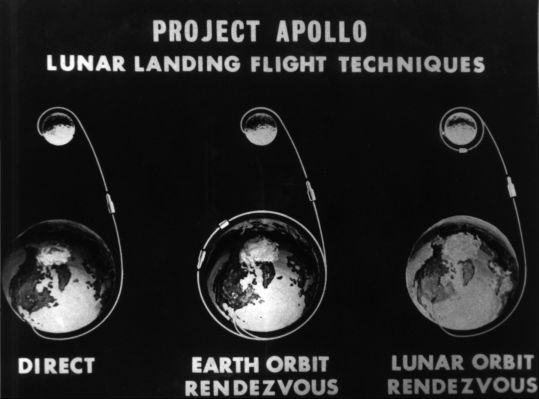

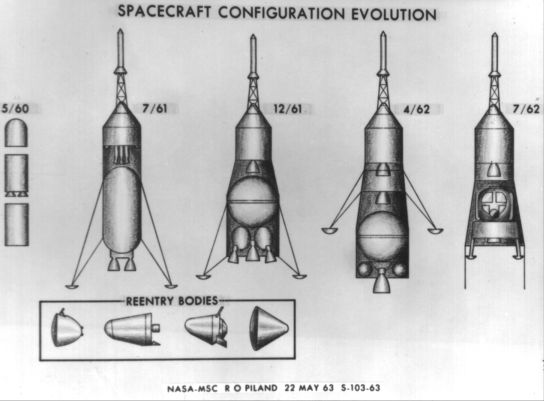

Politically setting a goal of manned lunar landing during the 1960s meant little technologically until somebody decided on the best way to fly there and back. Numerous suggestions had been made as to how to make the trip. Some sounded logical, some read like science fiction, and each proposal had vocal and persistent champions. All had been listened to with interest, but with no compelling need to choose among them. When President Kennedy introduced a deadline, however, it was time to pick one of the two basic mission modes - direct ascent or rendezvous - and, further, one of the variations of that mode. The story of Apollo told here thus far has only touched on the technical issues encountered along the tangled path to selecting the route.

Proposals: Before and after May 1961

NASA Administrator James Webb in early 1961 had inherited an agency assumption that direct ascent was probably the natural way to travel to the moon and back. It was attractive because it seemed simple in comparison to rendezvous, which required finding and docking with a target vehicle in space. But direct flight had drawbacks, primarily its need for the large rocket called Nova, which would be costly and difficult to develop. And the direct flight mission, itself, had been worked out only in the most general terms. At a meeting in Washington in mid-1960, the first NASA Administrator, Keith Glennan, had asked how a spacecraft might be landed on the moon. Max Faget of the Space Task Group had described a mission in which the spacecraft would first orbit the moon and then land, either in an upright position on deployable legs or horizontally using skids on the descent stage . Wernher von Braun of Marshall and William Pickering of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory JPL thought it would be unnecessary to orbit the moon first. As Faget recalled, “Dr. Pickering [said] you don’t have to go into orbit; . . . you just aim at the moon and, when you get close enough, turn on the landing rockets and come straight in. . . . I thought that would be a pretty unhappy day if, when you lit up the rockets, they didn’t light.”1

Direct flight also had supporters outside NASA. The Air Force had worked since 1958 on a plan for a lunar expedition. Called LUNEX, this proposal evolved from the earlier “Man-in-Space-Soonest” studies that had lost out in competition with Project Mercury. Major General Osmond J. Ritland, Commander of the Space Systems Division of the Air Force Systems Command, viewed LUNEX as a way to satisfy “a dire need for a goal for our national space program.” When President Kennedy announced on 25 May 1961 that a lunar landing would be that goal, the Space Systems Division offered to land three men on the moon and return them, using direct flight and a large three-stage booster. SSD believed the mission could be accomplished by 1967 at a cost of $7.5 billion.2

Rendezvous appeared dangerous and impractical to some NASA engineers, but to others it was the obvious way to eliminate the need for gigantic Nova-size boosters. Foremost among the variants in this approach was direct flight’s chief competitor, earth-orbit rendezvous (EOR). The von Braun group had revealed an interest in this mode when it briefed Glennan in December 1958 - long before its transfer from the Army to NASA. Von Braun had made a strong pitch for using EOR and the Juno V later Saturn booster, painting a pessimistic picture of developing anything large enough for direct ascent. Agreeing that direct flight was basically uncomplicated, von Braun nevertheless said he favored earth-orbit rendezvous because smaller vehicles could be employed. He sidestepped the problems of launching as many as 15 Saturns in rapid succession to rendezvous and dock in orbit to do the job,3

While working for the Army, the von Braun team published a study called “Project Horizon.” Billed as a plan for establishing a lunar military outpost, Horizon justified bases on the moon in terms of the traditional military need for high ground, but it emphasized political and scientific gains as well. Again, the operational techniques would require launching several rockets and refueling a vehicle in earth orbit before going on to the moon.4 On 18 June 1959, NASA Headquarters had asked the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA) for a study by the von Braun team of a lunar exploration program based on Saturn boosters. In its report of 1 February 1960, ABMA indicated there were several possibilities for a lunar mission, but only two - direct flight and earth-orbit rendezvous - seemed feasible. Reaffirming its authors’ belief in rendezvous around the earth as the most attractive approach, the report continued: “If a manned lunar landing and return is desired before the 1970’s, the SATURN vehicle is the only booster system presently under consideration with the capability to accomplish this mission.”5

After transferring to NASA and becoming the Marshall Space Flight Center, the von Braun group continued its plans for developing and perfecting its preferred approach. In January 1961, Marshall awarded 14 contracts for studies of launching manned lunar and planetary expeditions from earth orbit and for investigations of the feasibility of refueling in orbit.6 By mid-year, Marshall engineers were gathering NASA converts to help them push for earth-orbital rendezvous.

Across the country from Huntsville, another NASA center had different ideas about the best way to put man on the moon. Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, suggested a link-up of vehicles on the moon itself. A number of unmanned payloads - a vehicle designed to return to earth and one or more tankers - would land on the lunar surface at a preselected site. Using automatic devices, the return vehicle could then be refueled and checked out by ground control before the crew left the earth. After the manned spacecraft arrived on the moon, the crew would transfer to the fully fueled return vehicle for the trip home. One of the earliest proposals for this approach was put together by Allyn B. Hazard, a senior development engineer at the laboratory. His 1959 scheme laid the groundwork for JPL’s campaign for lunar-surface rendezvous during the Apollo mode deliberations.7

Even before the President’s May 1961 challenge, Pickering had tried to sell lunar-surface rendezvous to NASA’s long-range planners. Earlier that month, he had met in Washington with Abraham Hyatt, Director of Program Planning and Evaluation, to discuss this method of landing men on the moon. “We seriously believe,” he later wrote, “that this is a better approach to getting man there quickly than the approaches calling for a very large rocket.” Pickering favored this mode because the Saturn C-2 would be adequate for the job, unmanned spacecraft could develop the techniques of vertical descent and soft landings, NASA could space the launches months or even years apart, and the agency need not commit the manned capsule to flight until very late in the program (and then only if everything else was working properly). He admitted that the small payload capability of the C-2 would restrict the early missions to one-man flights but contended that “it is easy to extend the technique for larger missions, as larger rockets become available.”`8 Hyatt assured Pickering that Headquarters would examine all suggested modes, while confessing to a certain incredulity about this approach. “The idea . . . leaves me with very strong reservations,” Hyatt said.9

The fact that the United States had no large boosters in its inventory caused several farfetched schemes to surface. One such proposal promoted rendezvous and refueling while in transit to the moon, a concept pushed persistently by a firm named AstraCo. During the summer of 1960, AstraCo argued that this approach would “improve the mission capability of fixed-size earth launch systems.” At the request of Senator Paul H. Douglas, NASA officials met with two of the company’s representatives in Washington on 6 December 1960. After a discussion of the physical aspects of this kind of rendezvous and an analysis of fuel consumption and weight factors, the visitors were told that NASA was not interested. Three months later, on 14 March 1961, AstraCo took its case through another congressman to the NASA Administrator, and Webb asked his staff to take a second look. William Fleming and Eldon Hall calculated that rendezvous while on the way to the moon would save very little more weight and fuel than earth-orbit rendezvous and would be “far less reliable and consequently far more hazardous.” Fleming recommended that this scheme be turned down, once and for all. Webb concurred.10

Another approach was the proposal to send a spacecraft on a one-way trip to the moon. In this concept, the astronaut would be deliberately stranded on the lunar surface and resupplied by rockets shot at him for, conceivably, several years until the space agency developed the capability to bring him back! At the end of July 1961, E. J. Daniels from Lockheed Aircraft Corporation met with Paul Purser, Technical Assistant to Robert Gilruth, to discuss a possible study contract on this mode. Purser referred Daniels to NASA Headquarters. Almost a year later, in June 1962, John N. Cord and Leonard M. Seale, two engineers from Bell Aerosystems, urged in a paper presented at an Institute of Aerospace Sciences meeting in Los Angeles that the United States adopt this technique for getting a man on the moon in a hurry. While he waited for NASA to find a way to bring him back, they said, the astronaut could perform valuable scientific work. Cord and Seale, in a classic understatement, acknowledged that this would be a very hazardous mission, but they argued that “it would be cheaper, faster, and perhaps the only way to beat Russia.”11 There is no evidence that Apollo planners ever took this idea seriously.

Amid these likely and unlikely suggestions for overcoming the country’s limited booster capacity came yet another plan, lunar-orbit rendezvous (LOR), which seemed equally outlandish to many NASA planners. As the name implies, rendezvous would take place around the moon rather than around the earth. A landing craft, a separate module, would descend to the lunar surface. When the crew finished their surface activities, they would take off in the lander and rendezvous with the “mother” ship, which had remained in orbit about the moon. They would then transfer to the command module for the voyage back to the earth.12

Early in 1959 this mode was seen primarily as a way to reduce the total weight of the spacecraft. Although most NASA leaders appreciated the weight saving, the idea of a rendezvous around the moon, so far from ground control, was almost frightening.

Perhaps the first identifiable lunar-orbit rendezvous studies were those directed by Thomas Dolan of the Vought Astronautics Division, near Dallas. In December 1958, Dolan assembled a team of designers and engineers to study vehicle concepts, looking for ways for his company to share in any program that might follow Project Mercury. From mid-1959, the group concentrated on lunar missions, including a lunar landing, as the most probable prospect for future aerospace business. Dolan and his men soon came up with a plan they called MALLAR, an acronym for Manned Lunar Landing and Return.

Dolan’s group recognized very early that energy budgets were the keys to space flight (certainly no radical discovery). It conceived of a modular spacecraft, one having separate components to perform different functions. Dolan said, “One could perceive that some spacecraft modules might be applied to both Earth-orbital and lunar missions, embodying the idea of multimanned and multimodular approaches to space flight.” With this as the cornerstone of a lunar landing program, Dolan concluded that the best approach was to discard the pieces that were no longer needed. And he saw no reason to take the entire spacecraft down to the lunar surface and back to lunar escape velocity. MALLAR therefore incorporated a separate vehicle for the landing maneuver.13

At the end of 1959 the Dolan team prepared a presentation for NASA. Early in January 1960, J. R. Clark, Vice President and General Manager of Vought Astronautics, wrote Abe Silverstein about Dolan’s concept. The MALLAR proposal, Clark said, considered not only costs and vehicles but schedules. He also cited the advantages of the modular approach, mission staging, and the use of rendezvous.14

Nothing came of the proposal, although Dolan tried to interest NASA in MALLAR for the next two years. He found many technical people sympathetic to his ideas, but he was signally unsuccessful in winning financial support. He did get several small contracts from Marshall, but these were intended to bolster Marshall’s stand on rendezvous in earth orbit. Vought tried in vain to win part of Apollo, first competing for the feasibility study contracts in the latter half of 1960 and then, a year later, teaming with McDonnell Aircraft Corporation on the spacecraft competition. Because of these failures, Dolan and his group gradually lost the support of their corporate management.15 Thereafter, Chance Vought mostly faded out of the Apollo picture - although the company competed (and lost) once more, when the lunar landing module contracts were awarded in 1962.16

LOR Gains a NASA Adherent

At Langley Research Center, several committees were formed during 1959 and 1960 to look at the role of rendezvous in space station operations.* John Houbolt, Assistant Chief of the Dynamic Loads Division, who headed one of these groups, fought against being restricted to studies of earth-orbiting vehicles only. The mission the Houbolt team wanted to investigate was a landing on the moon.17

A more formal Lunar Missions Steering Group was established at Langley during 1960, largely through the efforts of Clinton E. Brown, Chief of the Theoretical Mechanics Division. The Lunar Trajectory Group within Brown’s division made intensive analyses of the mechanics in a moon trip. Papers on the subject were presented to the steering group and then widely disseminated throughout Langley.18

One of these monographs, by William Michael, described the advantage of parking the earth-return propulsion portion of the spacecraft in orbit around the moon during a landing mission. Michael explained that leaving this unit, which was not needed during the landing, in orbit would save a significant weight over that needed for the direct flight method; the lander, being smaller, would need less fuel for landing and takeoff. But he cautioned that this economy would have to be measured against the “complications involved in requiring a rendezvous with the components left in the parking orbit.”19

Brown’s steering group looked closely at total weights and launch vehicle sizes for lunar missions, comparing various modes. Arthur Vogeley, in particular, concentrated on safety, reliability, and potential development programs; Max Kurbjun studied terminal guidance problems; and John Bird worked on designs for a lander. They concluded that lunar rendezvous was the most efficient mode they had studied.20

Work at Langley then slackened somewhat, since NASA’s manned lunar landing plans seemed to be getting nowhere. On 14 December 1960, however, personnel from Langley went to Washington to brief Associate Administrator Robert Seamans on the possible role of rendezvous in the national space program. When he first joined NASA, three months earlier, Seamans had toured the field centers. At Langley, Houbolt had given him a 20-minute talk on lunar-orbit rendezvous, using rough sketches to illustrate his theory. Seamans had been sufficiently impressed by this brief discussion to ask Houbolt and his colleagues to come to Washington in December and make a more formal presentation. At this meeting, Houbolt spoke on the value of rendezvous to space flight; Brown presented an analysis of the weight advantages of lunar-orbit rendezvous over direct flight; Bird talked about assembling components in orbit; and Kurbjun gave the results of some simulations of rendezvous, indicating that the maneuver would not be very difficult.

Houbolt closed the session, remarking that rendezvous was an undervalued technique so far, but NASA should seriously consider its worth to the lunar landing program. Several members of Seamans’ staff viewed the weight-saving claims with skepticism,21 but Seamans was understanding. He had just completed a study for the Radio Corporation of America on the interception of satellites in earth orbit, and it occurred to him that some of the concepts he had studied might well be adapted to lunar operations.22

Back in Virginia, the Langley researchers had been trying to get their Space Task Group neighbors interested in rendezvous for Apollo. On 10 January 1961, Houbolt and Brown briefed Kurt Strass, Owen Maynard, and Robert L. O’Neal. O’Neal, who reported to Gilruth on the meeting, was less than enthusiastic about the lunar-orbit rendezvous scheme. He conceded that it might reduce the weight 20 percent, but “any other than a perfect rendezvous would detract from the system weight saving.”23

From December 1960 to the summer of 1961, Langley continued its analyses of lunar-orbit rendezvous as it applied to a manned lunar landing. Bird and Stone, among others, studied hardware concepts and procedures, including designs and weights for a lunar lander, landing gear, descent and ascent trajectories between the landing site and lunar orbit, and final rendezvous and docking maneuvers. Their findings were distributed in technical reports throughout NASA and in papers presented to professional organizations and space flight societies.24

In the spring of 1961, these Langley engineers compiled a paper proposing a three-phase plan for developing rendezvous capabilities that would ultimately lead to manned lunar landings: (1) MORAD (Manned Orbital Rendezvous and Docking), using a Mercury capsule to prove the feasibility of manned rendezvous and to establish confidence in the techniques; (2) ARP (Apollo Rendezvous Phase), using Atlas, Agena, and Saturn vehicles to develop a variety of rendezvous capabilities in earth orbit; and (3) MALLIR** (Manned Lunar Landing Involving Rendezvous), employing Saturn and Apollo components to place men on the moon. Houbolt urged that NASA implement this program through study contracts.25

- Most deeply engaged in Langley’s rendezvous studies were John Bird, Max C. Kurbjun, Ralph W. Stone, Jr., John M. Eggleston, Roy F. Brissenden, William H. Michael, Jr., Manuel J. Queijo, John A. Dodgen, Arthur Vogeley, William D. Mace, W. Hewitt Phillips, Clinton E. Brown, and John C. Houbolt.

- MALLIR embodied lunar-orbit rendezvous and a separate landing craft. Because America had no launch vehicle large enough to send a craft to the moon with only one earth launch, it also required an earth-orbital rendezvous before the spacecraft departed on a lunar trajectory.

Early Reaction to LOR

When the special NASA committees in 1961 (see Chapter 2) were trying to get the Apollo program defined, Houbolt made the rounds, making certain that everyone knew of Langley’s lunar-orbit rendezvous studies. At a meeting of the Space Exploration Program Council on 5 and 6 January, his arguments for lunar rendezvous were lost in the attention being given to direct flight and earth-orbit rendezvous.26 In Washington on 27 and 28 February, when Headquarters sponsored an intercenter rendezvous meeting, Houbolt again summarized Langley’s recent efforts. But both the Gilruth and von Braun teams stood solidly behind their respective positions, direct flight and earth-orbit rendezvous. Houbolt later recalled his frustration when it seemed lunar-orbit rendezvous “just wouldn’t catch on.”27

On 19 May, Houbolt bypassed the chain of command and wrote directly to Seamans to express his belief that rendezvous was not receiving due consideration. He pointed out that the American booster development program was in poor shape and that NASA appeared to have no firm plans beyond the initial version of the Saturn, the C-1. Houbolt was equally critical of NASA’s failure to recognize the need for developing rendezvous techniques. Because of the lag in launch vehicle development, he said, it seemed obvious that the only mode available to NASA in the next few years would be rendezvous.28

In June Houbolt, a member of Bruce Lundin’s group - the first team specifically authorized to examine anything except direct flight - talked to the group about his concept. Although the Lundin Committee initially seemed interested in Houbolt’s description of lunar-orbit rendezvous, only lunar-surface rendezvous scored lower in its final report.29

During July and August, Houbolt had almost the same reaction from Donald Heaton’s committee. Although this group had been instructed to study rendezvous, the members interpreted that mandate as limiting them to the earth-orbit mode. Houbolt, himself a member of the committee, pleaded with the others to include lunar-orbit rendezvous; but, he later recalled, time after time he was told, “No, no, no. Our charter [applies only to] Earth orbit rendezvous.” Some of the members, seeing how deeply he felt about the mode question, told him to write his own report to Seamans, explaining his convictions in detail.

Growing discouraged at the lack of interest, Houbolt and his Langley colleagues began to see themselves as sole champions of the technique. They decided to change their tactics. “The only way to do it,” Houbolt said later, was “to go out on our own, present our own documents and our own findings, and make our case sufficiently strong that people [would] have to consider it.”30

Houbolt felt that things were looking up when the Space Task Group asked him to prepare a paper on rendezvous for the Apollo Technical Conference in mid-July 1961. At the dry run, however, when he and the other speakers presented their papers for final review, Houbolt was told to confine himself to rendezvous in general and to “throw out all [that] LOR.”31

The next opportunity Houbolt had to fight for his cause came when Seamans and John Rubel established the Golovin Committee. Nicholas Golovin and his team were supposed to recommend a set of boosters for the national space program, but they found this an impossible task unless they knew how the launch vehicles would be used. This group was one of the first to display serious interest in Langley’s rendezvous scheme. At a session on 29 August, when Houbolt was asked, “In what areas have you received the most violent criticism of these ideas?” he replied:

Everyone says that it is hard enough to perform a rendezvous in the earth orbit, how can you even think of doing a lunar rendezvous? My answer is that rendezvous in lunar orbit is quite simple - no worries about weather or air friction. In any case, I would rather bring down 7,000 pounds [3,200 kilograms] to the lunar surface than 150,000 pounds [68,000 kilograms]. This is the strongest point in my argument.32

Realizing that he at last had his chance to present his plan to a group that was really listening, Houbolt called John Bird and Arthur Vogeley, asking them to hurry to Washington to help him brief the Golovin Committee. Afterward the trio returned to Langley and compiled a two-volume report, describing the concept and outlining in detail a program based on the lunar-orbit mode. Langley’s report was submitted to Golovin on 11 October 1961. After it had been thoroughly reviewed, its highlights were discussed, favorably, in the Golovin report.33

Instead of resting after his labors with the Golovin Committee, Houbolt went back to Langley and the task of getting out his minority report on the Heaton group’s findings. He submitted it to Seamans in mid November, with a cover note that said, in part, “I am convinced that man will first set foot on the moon through the use of ideas akin to those expressed herein.”34 His report to Seamans, a nine-page indictment of the planning for America’s lunar program to date, was a vigorous plea for consideration of Langley’s approach.

“Somewhat as a voice in the wilderness,” he began, “I would like to pass on a few thoughts on matters that have been of deep concern to me over the recent months.” Houbolt explained to Seamans that he was skipping the proper channels because the issues were crucial. After recounting his attempts to draw the attention of others in NASA to the lunar-orbit rendezvous scheme, Houbolt noted that, “regrettably, there was little interest shown in the idea.”

He went on to ask, “Do we want to get to the moon or not?” If so, why not develop a lunar landing program to meet a given booster capability instead of building vehicles to carry out a preconceived plan? “Why is NOVA, with its ponderous [size] simply just accepted, and why is a much less grandiose scheme involving rendezvous ostracized or put on the defensive?” Noting that it was the small Saturn C-3 that was the pacing item in the lunar rendezvous approach, he added, parenthetically, “I would not be surprised to have the plan criticized on the basis that it is not grandiose enough.”

A principal charge leveled at lunar-orbit rendezvous, Houbolt said, was the absence of an abort capability, lowering the safety factor for the crew. Actually, he argued, the direct opposite was true. The lunar-rendezvous method offered a degree of safety and reliability far greater than that possible by the direct approach, he said. But “it is one thing to gripe, another to offer constructive criticism,” Houbolt conceded. He then recommended that NASA use the Mark II Mercury in a manned rendezvous experiment program and the C-3 and lunar rendezvous to accomplish the manned lunar landing.35

Seamans replied to Houbolt early in December. “I agree that you touched upon facets of the technical approach to manned lunar landing which deserve serious consideration,” Seamans wrote. He also commended Houbolt for his vigorous pursuit of his ideas. “It would be extremely harmful to our organization and to the country if our qualified staff were unduly limited by restrictive guidelines.” The Associate Administrator added that he believed all views on the best way to carry out the manned lunar landing were being carefully weighed and that lunar-orbit rendezvous would be given the same impartial consideration as any other approach.36

Analysis of LOR

Most of the early criticism of the lunar rendezvous scheme stemmed from a concern for overall mission safety. In the minds of many, rendezvous - finding and docking with a target - would be a difficult task even in the vicinity of the earth. This concern was the underlying reason for the trend toward larger and larger Saturns (C-2 through C-5) to lessen the number of maneuvers required. After all, von Braun had once suggested that as many as 15 launchings of the smaller launch vehicles might be needed for one mission. During earth-orbital operations, the crew could return to the ground if they failed to meet their target vehicle or had other troubles. In lunar orbit, where the crew would be days away from home, a missed rendezvous spelled death for the astronauts and raised the specter of an orbital coffin circling the moon, perhaps forever. And all this talk about rendezvous came at a time when NASA had only a modicum of space flight experience of any kind. It is not surprising, therefore, that Houbolt had trouble swinging others away from their advocacy of direct flight or earth-orbit rendezvous.

Fears for crew safety and lack of experience were not the only factors; the Langley approach was criticized on another score - one as damning as the danger of a missed rendezvous. One of the principal attractions of Houbolt’s mode was the weight reduction it promised; but he and his colleagues, in trying to sell the mode, had oversold this aspect. Many who listened to the Langley team’s proposals simply did not believe the weight figures cited, especially that given for the lunar landing vehicle. In the lunar mission studies at Vought Astronautics, Dolan and his team had given much thought to designing the hardware, including a landing vehicle. Their weight calculations for a two-man lunar landing module were much higher than those proposed by the Langley engineers. Vought’s study projected a 12,000-kilogram vehicle, most of which was fuel. Empty, the lander would weigh only 1,300 kilograms.37

But, until late 1961, no one in NASA except Langley had really looked very hard at lunar landing vehicles. Using theoretical analyses and simulations, the rendezvous team at the Virginia center had studied hardware, “software” (procedures and operational techniques), flight trajectories, landing and takeoff maneuvers, and spacecraft systems (life support, propulsion, and navigation and guidance).38 The studies formed a solid foundation for technical design concepts for a landing craft.

Langley’s brochure for the Golovin Committee described landers of varied sizes and payload capabilities. There were illustrations and data on a “shoestring” vehicle, one man for 2 to 4 hours on the moon; an “economy” model, two men and a 24-hour stay time; and a “plush” module, two men for a 7-day visit. Weight estimates for the three craft, without fuel, were 580, 1,010, and 1,790 kilograms, respectively. Arthur Vogeley pictured the shoestring version as a solo astronaut perched atop an open rocket platform with landing legs. To expect Gilruth’s designers to accept such a “Buck Rogers space scooter” would seem somewhat optimistic.39

The same sort of minimal design features extended to subsystems, and structural weights further reflected Langley’s drive toward simplicity. In February 1961, at NASA’s intercenter rendezvous conference, Lindsay J. Lina and Vogeley had described the most rudimentary navigation and guidance equipment: a plumb bob, an optical sight, and a clock. This three-component system was feasible, they said, “only because maximum advantage is taken of the human pilot’s capabilities.” Even some of those on the Langley team criticized this kind of thinking; John Eggleston, for one, labeled it impractical.40

Despite Houbolt’s frustration, his missionary work had stimulated interest outside Langley. Within the Office of Manned Space Flight, George Low, Director of Spacecraft and Flight Missions, commented that “the ‘bug’ approach may yet be the best way of getting to the moon and back.”41 And Houbolt had finally struck a responsive chord when giving his sales talk to the Space Task Group in August. At this briefing, James Chamberlin, Chief of the Engineering Division, had been very attentive and had requested copies of the Langley documents. All during the year, Chamberlin and his team had been working on a study of putting two men in space in an enlarged Mercury capsule (which later emerged as Project Gemini).42 Although this successor to Mercury had been conceived as earth-orbital and long-duration, Chamberlin thought it might fly to the moon, as well. Seamans recalled that Chamberlin “was trying to develop something that was almost competitive with the Apollo itself.” Chamberlin did, indeed, offer an alternative to Apollo. He and several of his colleagues proposed using the two-man craft and lunar rendezvous in conjunction with a one-man lunar lander, which in many respects resembled the small vehicles studied by Lang1ey.43

Although Chamberlin could get approval only for the earth-orbital part of his plan, one of his principal objectives - rendezvous - was highly significant. It marked the beginning of the first important shift in the Apollo mode. Gilruth and his engineers began to perceive advantages they had not previously appreciated.

Growing interest in lunar-orbit rendezvous stemmed partially from disenchantment with direct flight. The Space Task Group had become increasingly apprehensive about landing on the moon in one piece and with enough fuel left to get back to earth. The command section it had under contract was designed as an earth-orbital, circumlunar, and reentry vehicle. It could not fly down to the surface of the moon. Lunar rendezvous, which called for a separate craft designed for landing, became more inviting.44

Gilruth’s engineers had worked on several designs for a braking rocket for lunar descent. In a working paper released in April 1961, Apollo planners had tried to size a propulsion system for landing, even though no booster had yet been chosen to get it to the moon. Two methods for landing were explored. The first was to back the vehicle in vertically, using rockets to slow, then stop, the spacecraft, setting it down on its deployed legs. The second technique was to fly the spacecraft in horizontally, like an aircraft. In this case, the legs would be deployed from the side of the craft instead of from the bottom.45

In the summer of 1961, when the command module contract was being advertised, Max Faget described some of the problems he anticipated with the landing itself. All other phases of the mission could be analyzed with a fair degree of certainty, he said, but the actual touchdown could not, since there was no real information on the lunar surface. Exhaust from rocket engines on loose rocks and dust might damage the spacecraft, interfere with radar, and obstruct the pilot’s vision. Faget said the final hovering and landing maneuvers must be controlled by the crew to ensure landing on the most desirable spot. The Apollo development plan, in its many revisions, merely said that the lunar landing module would be used for braking, hovering, and touchdown, as well as a base for launching the command ship from the moon.46

About the time of the contract award, Abe Silverstein left NASA Headquarters to become Director of Lewis Research Center.47 It had become increasingly apparent that Apollo would probably use one rendezvous scheme or another, and he was among the staunchest advocates of big booster power and direct flight. Concurrently with Silverstein’s return to Cleveland, Lewis was assigned to develop the lunar landing stage. Gilruth and Faget did not like this division of labor, as it added a complex management setup to the technical difficulties of matching spacecraft and landing stage.

Faget proposed a different propulsion module from the one previously envisioned for the descent to the lunar surface. He suggested taking the legs off the landing module and making it into just a braking stage, which he called a “lunar crasher.” Once this stage had eased the spacecraft down near the surface, it would be discarded to crash elsewhere before the Apollo touched down. The Apollo spacecraft would then consist of the command center and two propulsion modules, one to complete the landing and the other to boost the command module from the surface. Since the crasher’s only job was to slow the spacecraft, it was not part of the vehicle’s integral systems, which decreased the technical interfaces required and minimized Lewis’ role in the hardware portion of Apollo. Faget based his proposal on some sound technical reasoning. The crasher engines would be pressure-fed, no pumps would be needed, and the vehicle could be controlled by turning the engines off and on as long as the propellant lasted. Pump-fed engines, on the other hand, depended on complex interactions to vary the thrust. Faget and Gilruth liked the pressure-fed system, and so did Silverstein.48

Although relations with Lewis were easier after the adoption of the crasher, the Houston engineers were still worried about the complexities of an actual landing. As Faget later said, “We had all sorts of little ideas about hanging porches on the command module, and periscopes and TV’s and other things, but the business of eyeballing that thing down to the moon didn’t really have a satisfactory answer. . . . The best thing about the [lunar rendezvous concept] was that it allowed us to build a separate vehicle for landing.”49 Caldwell Johnson, one of the chief contributors to the Apollo command module design, had much the same reaction. He said, “We continued to pursue the landing with a big propulsion module and the whole command and service module for a long, long time, until it finally became apparent that this wasn’t going to work.”50

By the end of 1961, the newly named Manned Spacecraft Center had virtually swung over to the lunar-orbit rendezvous idea. Gilruth, Faget, and the other Apollo planners conceded that this approach had drawbacks: a successful rendezvous with the mother craft after the bug left the lunar surface was an absolute necessity, and only two of the three crew members would be able to land on the moon. But the stage had been set for an intensive campaign to sell the von Braun team on this mode. At Headquarters, Director of Manned Space Flight Holmes wanted the two manned space flight centers to agree on a single route - he did not expect to get this consensus easily.`51

Settling the Mode Issue

At the beginning of 1962, Holmes was not sure how he would vote on the lunar landing technique. Von Braun, among others, had made it clear that direct ascent, requiring the development of a huge Nova vehicle, was too much to ask for within the decade. However, both earth- and lunar-orbit rendezvous appeared equally feasible for accomplishing the moon mission within cost and schedule constraints. The decision, Holmes knew, would require weighing many technological factors. After directing Joseph Shea, his deputy for systems, to review the issue and recommend the best approach, Holmes laid down a second and broader objective. Shea was to use the task to draw Huntsville and Houston together, building a more unified organization with greater internal strength and cooperation.52

In mid-January 1962, Shea visited both the Manned Spacecraft and the Marshall Space Flight Centers. He found Houston officials enthusiastic about lunar-orbit rendezvous but believed they did not fully understand all the problems. He reported their low weight estimates as unduly optimistic. Marshall, on the other hand, still favored earth-orbit rendezvous. Shea did not think the Huntsville team had really studied lunar-orbit rendezvous thoroughly enough to make a decision either way.

From these brief sorties, Shea recognized the depth of the technical disagreement between the centers. He decided to bring the two factions together and make them listen to each other. During the next few months, Shea held a series of meetings at Headquarters, attended by representatives from all the centers working on manned space flight. At these briefings, the advocates presented details of their chosen modes to a captive audience. The first of these gatherings, featuring earth-orbit rendezvous, was held on 13 to 15 February 1962.53

Headquarters may not have realized it, but the sense of urgency surrounding the mode question was shared by the field. Recognizing that the need for choosing a mission approach was crucial, Gilruth’s men hastened to strengthen their technical brief. The Houston center notified Headquarters in January that it was going to award study contracts on two methods of landing on the moon, with either the entire spacecraft or a separate module, hoping one of the contractors would do a good enough job to be chosen as a sole source for a development contract.54 But Washington moved before the center could act.

Holmes and Shea had decided that lunar rendezvous needed further investigation. A contract supervised by Headquarters would tend to be more objective than one monitored by the field. A request for proposals was drawn up and issued at the end of January, and a bidders’ conference was held on 2 February in Washington. Although this contract was small, it was critical, and representatives from a dozen aerospace companies attended the conference. Those intending to bid were given only two weeks to respond. Shea and his staff, with the help of John Houbolt, evaluated the proposals and announced on 1 March that Chance Vought had been selected.55

Chance Vought’s study ran for three months and was significant mainly because of its weight estimates. Houston calculated that the target weight of the lunar landing module would be 9,000 kilograms, but Chance Vought came up with a more realistic figure of 13,600 kilograms. Shea and his team, in the subsequent mode comparisons, used Chance Vought’s higher weight projections.56

Holmes’ Management Council was also studying the mission approach. On 6 February, with Associate Administrator Seamans present, the group heard another of Houbolt’s briefings on lunar- versus earth-orbit rendezvous. Charles Mathews, Chief of the Spacecraft Research Division, then described Houston’s studies of the lunar-rendezvous mode. Von Braun interjected that selection of any rendezvous method at that time was premature.57

On 27 March, the council discussed the Chance Vought study. Several of the members were concerned about the weight the contractor was estimating the Saturn C-5 would have to lift, compared with that projected by the Houston center 38,500 kilograms against 34,000. This disparity was very serious, since Chance Vought’s work would be useless if Marshall decided that the C-5 could not manage the heavier load. The council also noted that the mode issue was beginning to affect other elements of the program adversely. North American was designing the service module to accommodate either form of rendezvous; but, as more detail was incorporated into the design, being able to go both ways would cost more in weight and complexity.58

On 2 and 3 April, Shea called field center officials to a meeting on lunar-orbit rendezvous. After some basic ground rules for operations and hardware designs had been laid down, it became obvious to Shea that there were still too many unresolved questions. He told the company to go back home and continue the studies.59

About this time, a small group in Houston took up the campaign for lunar-orbit rendezvous waged earlier by Houbolt. Charles W. Frick, who headed the newly formed Apollo Spacecraft Project Office at Manned Spacecraft Center, had aerospace management experience in both research and manufacturing - first at Ames Research Center for NASA and then with General Dynamics Convair for industry. Frick saw Marshall, rather than Headquarters, as the strategic target for an offensive. Frick said, “It became apparent that the thing to do was to talk to Dr. von Braun, in a technical sense, . . . perhaps with a bit of showmanship, and try to convince him.”60

During February 1962, Frick and his project office staff briefed Holmes on why they favored lunar rendezvous. Frick ruefully admitted later that they did a rather poor job. “So when we got back [to Houston] we got our heads together and decided that we just weren’t putting down [enough] technical detail.” He formed a small task force, drawn from his own project people and Max Faget’s engineering directorate, to pull the information together.61

William Rector of Frick’s office got busy on this more persuasive presentation. The result, a carefully staged affair that became known as “Charlie Frick’s Road Show,” consisted of briefings by half a dozen speakers. The opening performance was staged in Huntsville before von Braun and his subordinates on 16 April 1962. To emphasize the importance of the message, the Houston group included all of the leading lights of the center - Gilruth, his top technical staff, and several astronauts - as well as senior Apollo officials from North American the command module contractor .

In a day-long presentation, Frick’s troupe explained three technical reasons for his center’s conversion to lunar-orbit rendezvous: (1) highest payload efficiency, (2) smallest size for the landing module, and (3) least compromise on the design of the spacecraft. The advantages of a separate lander all listed in Houbolt’s minority report to Seamans, which would neither take off from nor land on the earth, loomed large, since Gilruth and his men believed that landing on the moon would be the most difficult phase of Apollo and they wanted the simplest landing possible.62

Frick and his road company next headed for Washington, where they gave two performances - for Holmes on 3 May and for Seamans on 31 May.63 The Houston center’s drive to sell lunar rendezvous thus followed the path traveled by Houbolt a year earlier. Although it doubtless reinforced his arguments, it appeared to have no other effect.

In budgetary hearings before Congress in the spring of 1962, NASA officials named earth-orbit rendezvous as the best mode for Apollo, with direct flight as the backup. NASA Deputy Administrator Dryden said, on 16 April, “As we see it at the moment, we are putting our bets on a rendezvous [in earth orbit] with two advanced Saturn’s.” However, Dryden continued, “if we find that we are not able to do this mission by rendezvous, we would be in a bad way.”64

When asked by members of the House Subcommittee on Manned Space Flight about approaches other than earth-orbit rendezvous and direct flight, Holmes admitted that lunar rendezvous was also interesting. The mission could theoretically be performed with a single Saturn C-5, Holmes went on, but it was considered too hazardous, since failure to rendezvous around the moon would doom the crew.65

Early in May, yet another scheme for landing men on the moon appeared. A study for a direct flight, using a C-5 and a two-man crew, had been quietly considered at the Ames and Lewis Research Centers and at North American. Although there were objections from Houston, Shea hired the Space Technology Laboratories to investigate this C-5 direct mode.66

Other researchers at Ames spent a great deal of time on plans that revealed their dislike of lunar rendezvous. Alfred Eggers and Harold Hornby, in particular, traded information and mulled over rendezvous modes with North American engineers. Hornby favored a method that resembled von Braun’s December 1958 idea, arguing the advantages of some sort of salvo rendezvous in earth orbit. When he realized that NASA Headquarters was on the brink of making the mode decision, Eggers kept urging Seamans to reopen the whole question of the safest, most economical way to reach the moon.67

Shea, having promised Holmes a preliminary recommendation on the mode by mid-June, increased the pressure on the field centers to continue their research for the coordination meetings. On 25 May Holmes asked the Directors of the three manned space flight centers to submit cost and schedule estimates for each of the approaches under consideration.68 Shea began collecting his material for final review, although there was still no agreement between Huntsville and Houston. Despite Frick’s road show, the Marshall center persisted in its preference for earth-orbit rendezvous. The mode comparison meetings had obviously been less than successful in bringing the two opponents together. “I was pretty convinced now that you could do either EOR or LOR,” Shea later said, “so the choice . . . was really . . . what’s the best way.”69

Holmes and Shea, in addition to deciding on the best approach, were still determined to settle for nothing short of unanimity. They scheduled yet another series of meetings at each center, “in which we asked them to summarize their studies and draw conclusions” so everyone would feel like a real part of the technical decision process.70

Shortly before these summary meetings in May and June of 1962, the mounting tide of evidence favoring lunar-orbit rendezvous reached its flood. Shea and Holmes became convinced that this was indeed the best approach. But, if they were to have harmony within their organization, Marshall must be won over. Holmes asked Shea to discuss lunar-orbit rendezvous in depth with von Braun and to explore his reaction to the crimp this mode would put in Marshall’s share of Apollo. Since lunar rendezvous would require fewer boosters than the earth-orbital mode and since Marshall would have no part in developing docking hardware and rendezvous techniques, the Huntsville role would diminish considerably. Also, with the Nova’s prospects definitely on the wane, Marshall’s long-term future seemed uncertain.

For some time von Braun and his colleagues had wanted to broaden the scope of their space activities, and Holmes knew it. He and Shea decided that this was the time to offer von Braun a share of future projects, including payloads, to balance the workload between Houston and Huntsville.

About the middle of May, von Braun visited Washington, and Shea told him that lunar rendezvous appeared to be shaping up as the best method. Conceding that it might well be a wise choice, the Marshall Director again expressed concern for the future of his people. Shea acknowledged that Marshall would lose a good deal of work if NASA adopted lunar rendezvous, but he reminded von Braun that

Houston would be very loaded with both the CSM [command and service modules] and the LEM [lunar excursion module]. It just seems natural to Brainerd and me that you guys ought to start getting involved in the lunar base and the roving vehicle and some of the other spacecraft stuff. . . . Wernher kind of tucked that in the back of his mind and went back to Huntsville.71

Huntsville was not the only center that faced a loss of business if lunar-orbit rendezvous were chosen. Lewis would also be left standing at the gate, since that mode would eliminate the need for the lunar crasher. The Cleveland group did hope to capitalize on liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen technology for other pieces of the Saturn propulsion requirements, although this, of course, would mean a contest with Marshall.72

The Management Council met in Huntsville on 29 May, two weeks after the confidential talk between Shea and von Braun. Perhaps in compliance with his implied promise to the Marshall Director, Shea opened the subject of an unmanned logistics vehicle to deposit supplies on the moon, increasing the time that a manned spacecraft could remain on the lunar surface. George Low warned that developing a logistics vehicle should not be a prerequisite to a manned lunar landing.73 Houston questioned the usefulness of unmanned supply craft “because of the reliability problems of unmanned vehicles, and . . . whether supplies [previously deposited] on the moon could be effectively used.” Gilruth’s men argued that any such vehicle should not simply be an Apollo lunar excursion vehicle modified for unmanned operation. The best approach would be a “semisoft” lander, similar to unmanned spacecraft like Surveyor. And Gilruth’s engineers were quick to point out that logistic support could be obtained by attaching a “mission module” to a manned lunar module, since the Saturn C-5 should eventually be able to handle an additional 1,600 kilograms of supplies and equipment.74

Shea’s special meetings on the centers’ mode studies resumed in early June. By far the most significant was an all-day affair at Marshall on 7 June, where von Braun’s lieutenants catalogued the latest results of their research. “The tone of everything [throughout the day] in the presentations by his people was all very pro-EOR,” Shea recalled. At the end, after six hours of discussion on earth-orbit rendezvous, von Braun dropped a bomb that, as far as internal arguments in NASA were concerned, effectively laid the Apollo mode issue to rest. To the dismay of his staff, said Shea, von Braun “got up and in about a 15-minute talk that he’d handwritten during the meeting stated that it was the position of [his] Center to support LOR.”75

“Our general conclusion,” von Braun told his startled audience, “is that all four modes are technically feasible and could be implemented with enough time and money.” He then listed Marshall’s preferences: (1) lunar-orbit rendezvous, with a recommendation to make up for its limited growth potential to begin simultaneous development of an unmanned, fully automatic, one-way C-5 logistics vehicle; (2) earth-orbit rendezvous, using the refueling technique; (3) direct flight with a C-5, employing a lightweight spacecraft and high-energy return propellants; and (4) direct flight with a Nova or Saturn C-8. Von Braun continued:

I would like to reiterate once more that it is absolutely mandatory that we arrive at a definite mode decision within the next few weeks. . . . If we do not make a clear-cut decision on the mode very soon, our chances of accomplishing the first lunar expedition in this decade will fade away rapidly.

The Marshall chief then explained his about-face. Lunar rendezvous, he had come to realize, “offers the highest confidence factor of successful accomplishment within this decade.” He supported Houston’s contention that designing the Apollo reentry vehicle and the lunar landing craft were the most critical tasks in achieving the lunar landing. “A drastic separation of these two functions into two separate elements is bound to greatly simplify the development of the spacecraft system [and] result in a very substantial saving of time.”

Moreover, lunar-orbit rendezvous would offer the “cleanest managerial interfaces” - meaning that it would reduce the amount of technical coordination required between the centers and their respective contractors, a major concern in any complex program. Apollo already had a “frightening number” of these interfaces, since it took the combined efforts of many companies to form a single vehicle. And, finally, this mode would least disrupt other elements of the program, especially booster development, existing contract structures, and the facilities already under construction.

We . . . readily admit that when first exposed to the proposal of the Lunar Orbit Rendezvous mode we were a bit skeptical. . . .

We understand that the Manned Spacecraft Center was also quite skeptical at first, when John Houbolt of Langley advanced the proposal, . . . and it took quite a while to substantiate the feasibility of the method and finally endorse it.

Against this background it can, therefore, be concluded that the issue of “invented here” versus “not invented here” does not apply to either the Manned Spacecraft Center or the Marshall Space Flight Center; that both Centers have actually embraced a scheme suggested by a third source. Undoubtedly, personnel of MSC and MSFC have by now conducted more detailed studies on all aspects of the four modes than any other group. Moreover, it is these two Centers to which the Office of Manned Space Flight will ultimately have to look to “deliver the goods.” I consider it fortunate indeed . . . that both Centers, after much soul searching, have come to identical conclusions. This should give the Office of Manned Space Flight some additional assurance that our recommendations should not be too far from the truth.76

Casting the Die

Von Braun’s pronouncement in favor of lunar-orbit rendezvous, thus aligning his center with Gilruth’s in Houston, signaled the accord that Holmes and Shea had so meticulously cultivated. Von Braun’s conversion brought the two centers closer together, paving the way for effective cooperation. “It was a major element in the consolidation of NASA,” Shea said.77

Thereafter, ratification of the mode question - the formal decision-making process and review by top management - followed almost as a matter of course. The Office of Systems began compiling information from the field center studies, adding the result of its own mode investigations. Shea and his staff also listened to briefings from several aerospace companies who had studied lunar rendezvous and the mission operations and hardware requirements for that approach. These firms, among them Douglas and a team from Grumman and RCA, believed that such work might enhance their chances of securing the additional hardware contracts that would follow a shift to lunar rendezvous.78

Shea’s staff then compared the contending modes and prepared cost and schedule estimates for each. It appeared that lunar-orbit rendezvous should cost almost $1.5 billion less than either earth-orbit rendezvous or direct flight ($9.2 billion versus $10.6 billion) and would permit lunar landings six to eight months sooner.79

The Office of Systems issued the final version of the mode comparison at the end of July. This was the foundation upon which Holmes would defend his choice. Comparison of the modes revealed no significant technical problems; any of the modes could be developed with sufficient time and money, as von Braun had said. But there was a definite preferential ranking.

Lunar rendezvous, employing a single Saturn C-5, was the most advantageous, since it also permitted the use of a separate craft designed solely for the lunar landing. In contrast, earth rendezvous with Saturn C-5s had the least assurance of mission success and the greatest development complexity of all the modes. Direct flight with the Nova afforded greater mission capability but demanded development of launch vehicles far larger than the C-5. A scaled-down, two-man C-5 direct flight offered minimal performance margins and portended the greatest problems with equipment accessibility and checkout. Therefore, “the LOR mode is recommended as most suitable for the Manned Lunar Landing Mission.”80

On 22 June, Shea and Holmes had presented their findings to the Management Council. After extended discussions, the council unanimously agreed that lunar-orbit rendezvous was the best mode. To underscore the solidarity within the manned space flight organization, all of the members decided to attend when Administrator Webb was briefed on the mode selection.81

First, however, Holmes and Shea informed Seamans of the decision. “By then,” the Associate Administrator recalled, “I was thoroughly convinced myself, and everybody agreed on it.” This was a technical decision that, from a general management position, he had refused to force upon the field organizations, even though he had long thought that lunar rendezvous was preferable.82

On 28 June, Webb listened to the briefing and to the recommendations of the Management Council. He agreed with what was said but wanted Dryden, who was in the hospital, to take part in the final decision. That night, Seamans, Holmes, and Shea called on Dryden in his sickroom. Dryden had opposed lunar rendezvous because of the risks he believed it entailed, but he, too, liked the unanimity within the council and within NASA and gave lunar-orbit rendezvous his blessing.83

Although acceptance of lunar rendezvous by the agency came before the end of June 1962, it was not announced until the second week in July. The delay was caused by outside pressure. PSAC, the President’s Science Advisory Committee, headed by Jerome Wiesner, had developed an interest in NASA’s launch vehicle planning and the mode selection for Apollo. Wiesner had formed a special group, the Space Vehicle Panel, to keep an eye on NASA’s doings, and Nicholas Golovin, no longer with NASA, worked closely with this panel. Wiesner had hired Golovin for PSAC because of his familiarity with the internal workings of the agency and his knowledge of the country’s space programs, both military and civilian. Golovin led a persistent and intensive review of Apollo planning that caused considerable turmoil within the agency and forced it into an almost interminable defense of its decision to use lunar rendezvous. Concurrently with Shea’s drive for field center agreement, the PSAC panel was holding meetings in Huntsville and Houston, demanding that the two centers justify their stand on lunar-orbit rendezvous. The panel then insisted on meeting with Shea and his staff in Washington for further discussions.84

In a memorandum on 10 July, approved by both Webb and Dryden, Seamans officially informed Holmes that the decision on the Apollo mode had been approved. The Rubicon was crossed; Apollo was to proceed with lunar rendezvous. Immediate development of both the Saturn C-IB and a lunar excursion vehicle was also approved. Seamans added that “studies will be undertaken on an urgent basis” to determine the feasibility of earth-orbit rendezvous using the C-5 and a two-man capsule, one “designed, if possible, for direct ascent . . . as a backup mode.”85

Webb, Seamans, Holmes, and Shea announced the selection of lunar-orbit rendezvous for Apollo at a news conference on 11 July 1962. Webb, perhaps as a concession to Wiesner, warned that the decision was still only tentative; during the forthcoming months, he added, the agency would solicit proposals for the lunar landing module from industry and would study them carefully before making a final decision. In the meantime, studies of other approaches would continue.

Holmes, however, struck a more definite note on the finality of the decision. Anything so complex, so expensive, as Apollo had to be studied at length, he said. “However, there is a balance between studying a program . . . and finally implementing it. There comes a point in time, and I think the point in time is now, when one must make a decision as to how to proceed, at least as the prime mode.”

Webb concluded the press briefing:

We have studied the various possibilities for the earliest, safest mission . . . and have considered also the capability of these various modes . . . for giving us an increased total space capability.

We find that by adding one vehicle to those already under development, namely, the lunar excursion vehicle, we have an excellent opportunity to accomplish this mission with a shorter time span, with a saving of money, and with equal safety to any other modes.86

Early the next morning, Holmes and Shea appeared before the House Committee on Science and Astronautics to explain NASA’s seemingly abrupt abandonment of earth-orbit rendezvous. Holmes said, “It was quite apparent last fall this mission mode really had not been studied in enough depth to commit the tremendous resources involved, financial and technical, for the periods involved, without making . . . detailed system engineering studies to a much greater extent than had been possible previously.” Nor had there been any agreement within the agency on any approach; “further study was necessary for that reason,” as well. But investigations could go on forever, he added, and “at some point one must make a decision and say now we go. It has been really impossible for us to truly program manage [Apollo] until this primary mode decision had been made.” Although several modes were workable, lunar-orbit rendezvous was “the most favorable one for us to undertake today.” Equally important was the new rapport that had been achieved within the manned space flight organization “to get the whole team pulling together.”87

“Essentially,” Holmes told an American Rocket Society audience a week later, “we have now ‘lifted off’ and are on our way.”88 But the PSAC challenge to NASA’s choice still had to be dealt with before the decision became irreversible. While fending off this outside pressure, NASA had to keep North American moving on the command and service modules, watch MIT’s work on the navigation and guidance system, and find a contractor for the lunar landing module.

ENDNOTES

- Maxime A. Faget, interview, Houston, 15 Dec. 1969; Ivan D. Ertel, notes on Caldwell C. Johnson interview, 10 March 1966. See also John M. Logsdon, “Selecting the Way to the Moon: The Choice of the Lunar Orbital Rendezvous Mode,” Aerospace Historian 18, no. 2 (June 1971): 63-70.X

- U.S. Air Force, “Lunar Expedition Plan: LUNEX,” USAF WDLAR-S-458, May 1961.X

- Wernher von Braun, Ernst Stuhlinger, and H[einz] H. Koelle, “ABMA Presentation to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration,” ABMA Kept. D-TN-1-59, 15 Dec. 1958, pp. 113-15.X

- U.S. Army, “Project Horizon, Phase I Report: A U.S. Army Study for the Establishment of a Lunar Military Outpost,” 8 June 1959, vol. 1, “Summary”: 1-3, 17-26; 2, “Technical Considerations and Plans,” passim, but esp. pp. 4-6, 139-41.X

- Army Ballistic Missile Agency, “A Lunar Exploration Based upon Saturn-Boosted Systems,” ABMA Kept. DV-TR-2-60, 1 Feb. 1960, pp. 224-40.X

- House Committee on Science and Astronautics, Aeronautical and Astronautical Events of 1961: Report, 87th Cong., 2nd sess., 7 June 1962, p. 3; idem, Orbital Rendezvous in Space: Hearing, 87th Cong., 1st sess., 23 May 1961, pp. 16-17; J. Thomas Markley to Assoc. Dir., STG, “Trip report . . . on May 10, 11, and 12, 1961 to Marshall Space Flight Center (Huntsville), Chance Vought (Dallas) and Douglas (Los Angeles),” 19 May 1961; Koelle to Robert R. Gilruth, “Mid-tem (6-month) Contractor Reviews on Orbital Launch Operations Study,” 22 May 1961.X

- [Nicholas E. Golovin], draft report of DoD-NASA Large Launch Vehicle Planning Group (LLVPG), 1 [November 1961], pp. 6B-39 through 6B-42; Allyn B. Hazard, “A Plan for Manned Lunar and Planetary Exploration,” November 1959.X

- William H. Pickering to Abraham Hyatt, 22 May 1961.X

- Hyatt to Pickering, 31 May 1961.X

- William A. Fleming to Admin., NASA, “Comments on In-transit rendezvous proposal by AstraCo,” 5 April 1961; Charles L. Kaempen, “Space Transport by In-Transit Rendezvous Techniques,” August 1960; James E. Webb to James Roosevelt, 26 April 1961.X

- Paul E. Purser to Gilruth, “Log for week of July 31, 1961,” 10 Aug. 1961; House Committee on Science and Astronautics, Astronautical and Aeronautical Events of 1962: Report, 88th Cong., 1st sess., 12 June 1963, p. 112; “Apollo Chronology,” MSC Fact Sheet 96, n.d., p. 19; John M. Cord and Leonard M. Scale, “The One-Way Manned Space Mission,” Aerospace Engineering 21, no. 12 (1962) : 60-61, 94-102.X

- [Golovin], draft rept., pp. 6B-36 through 6B-39.X

- Thomas E. Dolan, interview, Orlando, Fla., 14 Oct. 1968.X

- J. R. Clark to NASA, Attn.: Abe Silverstein, “Manned Modular Multi-Purpose Space Vehicle Program - Proposal For,” 12 Jan.1960, with enc., “Manned Modular Multi-Purpose Space Vehicle.”X

- Dolan interview; House Committee on Science and Astronautics, Orbital Rendezvous in Space, pp. 16-17; Markley to Assoc. Dir., STG, 19 May 1961; Koelle to Gilruth, 22 May 1961; “Participating Companies or Company Teams” in “Partial Set of Material for Evaluation Board Use,” n.d. [ca. 7 Sept. 1960]; NASA MSC, “Source Evaluation Board Report, Apollo Spacecraft, NASA RFP 9-150,” 24 Nov. 1961.X

- MSC, Apollo Spacecraft Program Off. (ASPO) activity rept., 23 Sept.-6 Oct. 1962; H. Kurt Strass, interview, Houston, 30 Nov. 1966.X

- John C. Houbolt, interview, Princeton, N.J., 5 Dec. 1966; Houbolt, “Lunar Rendezvous,” International Science and Technology 14 (February 1963): 62-70; John D. Bird, interview, Langley, 20 June 1966.X

- Bird interview; Bird, “A Short History of the Lunar-Orbit-Rendezvous Plan at the Langley Research Center,” 6 Sept. 1963 (supplemented 5 Feb. 1965 and 17 Feb. 1966); Houbolt, “Lunar Rendezvous,” p. 65.X

- William H. Michael, Jr., “Weight Advantages of Use of Parking Orbit for Lunar Soft Landing Mission,” in Jack W. Crenshaw et al., “Studies Related to Lunar and Planetary Missions,” Langley Research Center, 26 May 1960, pp. 1-2.X

- John M. Eggleston, interview, Houston, 7 Nov. 1966; Bird, “Short History,” p. 2; Bird interview.X

- Bird, “Short History,” p. 2; list of attendees at Briefing on Rendezvous for Robert C. Seamans, Jr., 14 Dec. 1960; Bird and Houbolt interviews.X

- Seamans, interview, Washington, 26 May 1966.X

- Robert L. O’Neal to Assoc. Dir., STG, “Discussion with Dr. Houbolt, LRC, concerning the possible incorporation of a lunar orbital rendezvous phase as a prelude to manned lunar landing,” 30 Jan. 1961.X

- For a listing of some of the results of these studies, see “Reports and Technical Papers Which Contributed to the Two Volume Work ‘Manned Lunar-Landing through Use of Lunar-Orbit-Rendezvous,’ by Langley Research Center,” Langley Research Center, n.d.; William D. Mace, interview, Langley, 20 June 1966. See also John C. Houbolt, “Problems and Potentialities of Space Rendezvous,” paper presented at the International Symposium on Space Flight and Re-Entry Trajectories, Louveciennes, France, 19-21 June 1961, published in Theodore von Kármán et al., eds., Astronautica Acta 7 (Vienna, 1961): 406-29.X

- Langley Research Center, “Manned Lunar Landing Via Rendezvous,” charts, n.d.; Bird, “Short History,” p. 3; Houbolt interview; Houbolt, “Lunar Rendezvous,” International Science and Technology, February 1963, pp. 62-70, 105.X

- Minutes, Space Exploration Program Council meeting, 5-6 Jan. 1961.X

- Floyd L. Thompson to NASA Hq., Attn.: Bernard Maggin, “Forthcoming Inter-NASA Meeting on Rendezvous,” 4 Jan. 1961, with enc.; E. J. Manganiello to NASA Hq., “Agenda for Orbital Rendezvous Discussions,” 5 Jan. 1961, with enc.; Bird and David F. Thomas, Jr., “Material for Meeting of Centers on Rendezvous, February 27-28, 1961: Studies Relating to the Accuracy of Arrival at a Rendezvous Point,” n.d.; agenda, NASA Inter-Center Rendezvous Discussions, General Meeting - 27-28 Feb. 1961; Bird, “Short History,” p. 3; Houbolt interview.X

- Houbolt to Seamans, 19 May 1961.X

- Bruce T. Lundin et al., “A Survey of Various Vehicle Systems for the Manned Lunar Mission,” 10 June 1961; Houbolt interview.X

- “Earth Orbital Rendezvous for an Early Manned Lunar Landing,” pt. 1, Summary Report of Ad Hoc Task Group [Heaton Committee] Study, August 1961; Houbolt interview.X

- Gilruth to General Dynamics Astronautics, Attn.: William F. Rector III, 27 June 1961, with enc., “Proposed Agenda, NASA-Industry Apollo Technical Conference, . . . July 18, 1961”; Thompson to STG, Attn.: Purser, “Rehearsal schedule for the NASA-Industry Apollo Technical Conference,” 3 July 1961, with enc.; John C. Houbolt, “Considerations of Space Rendezvous,” in “NASA-Industry Apollo Technical Conference July 18, 19, 20, 1961: A Compilation of the Papers Presented,” pt. 1, pp. 73, 79; Houbolt interview.X

- Minutes of presentation to LLVPG by Houbolt, 29 Aug. 1961.X

- Ibid.; [John C. Houbolt et al.], “Manned Lunar Landing through use of Lunar-Orbit Rendezvous,” 2 vols., LaRC, 31 Oct. 1961, p. i; Mike Weeks to LLVPG staff, no subj., 2 Oct. 1961, with encs.; Bird interview; Bird, “Short History,” p. 3.X

- Houbolt to Seamans, no subj., [ca. 15 Nov. 1961].X

- Houbolt to Seamans, 15 Nov. 1961 (emphasis in original).X

- Seamans to Houbolt, 4 Dec. 1961.X

- Richard B. Canright to James D. Bramlet et al., no subj., 27 Nov. 1961, with enc., Canright, “The Intermediate Vehicle,” 22 Nov. 1961; James F. Chalmers, minutes of LLVPG general meeting, 28 Aug. 1961; O’Neal memo, 30 Jan. 1961; Clark enc., “Manned Modular Multi-Purpose Space Vehicle.”X

- [Houbolt et al.], “Manned Lunar Landing through Lunar-Orbit Rendezvous”; Eggleston interview.X

- [Houbolt et al.], “Manned Lunar Landing through Lunar-Orbit Rendezvous”; Bird and Houbolt interviews.X

- Lindsay J. Lina and Arthur W. Vogeley, “Preliminary Study of a Piloted Rendezvous Operation from the Lunar Surface to an Orbiting Space Vehicle,” Langley Research Center, 21 Feb. 1961; Houbolt and Eggleston interviews.X

- George M. Low to Dir., NASA OMSF, “Comments on John Houbolt’s Letter to Dr. Seamans,” 5 Dec. 1961.X

- Purser to Gilruth, “Log for Week of August 28, 1961,” 5 Sept. 1961; Bird, “Short History,” p. 4; Houbolt interview; STG, “Preliminary Project Development Plan for an Advanced Manned Spacecraft Program Utilizing the Mark II Two Man Spacecraft,” 14 Aug. 1961.X

- Seamans interview, 26 May 1966; Harry C. Shoaf, interview, Cocoa Beach, Fla., 10 Oct. 1968.X

- Seamans interview, 26 May 1966; Purser to Howard Margolis, 15 Dec. 1970. See also John D. Hodge, John W. Williams, and Walter J. Kapryan, “Design for Operations,” in “NASA-Industry Apollo Technical Conference,” pt. 2, pp. 41-56.X

- H. K[urt] Strass, “A Lunar Landing Concept,” in Strass, ed., “Project Apollo Space Task Group Study Report, February 15, 1961,” NASA Project Apollo working paper no. 1015, 21 April 1961, pp. 166-74; Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, NASA Authorization for Fiscal Year 1961: Hearings on H.R. 6874, 87th Cong., 1st sess., 1961, pp. 71-75.X

- Maxime A. Faget, “Lunar Landing Considerations,” in “NASA-Industry Apollo Technical Conference,” pt. 1, pp. 89-97; STG, “Project Apollo Spacecraft Development, Statement of Work, Phase A,” 28 July 1961; STG, “Preliminary Project Development Plan for Apollo Spacecraft,” 9 Aug. 1964, pp. 7-10; MSC, “Project Apollo Spacecraft Development Statement of Work,” 27 Nov. 1961, p-p. 78-81.X

- Robert L. Rosholt, An Administrative History of NASA, 1958-1963, NASA SP-4101 (Washington, 1966), p. 222.X

- Seamans, interview, Washington,11 July 1969; Faget interview, 15 Dec. 1969; Faget, interview, comments on draft edition of this volume, Houston, 22 Nov. 1976.X

- Faget interview, 15 Dec. 1969.X

- Johnson, interview, Houston, 9 Dec. 1966.X

- Purser letter, 15 Dec. 1970.X

- Joseph F. Shea, interview, Washington, 6 May 1970.X

- Ibid.; Shea, “Trip Report on Visit to MSC at Langley and MSFC at Huntsville,” 18 Jan. 1962.X

- Paul F. Weyers to Mgr., ASPO, “Impact of lack of a decision on operational techniques on the Apollo Project,” 19 April 1962; A. B. Kehlet et al., “Notes on Project Apollo January 1960-January 1962,” 8 Jan. 1962, pp. 1, 7.X

- Shea memo for record, no subj., 26 Jan. 1962; Shea interview; “Apollo Chronology,” MSC Fact Sheet 96, p. 12; Purser to Gilruth, “Log for week of January 22, 1962,” 30 Jan. 1962, and “Log for week of February 12, 1962,” 26 Feb. 1962; Shea memo for file, no. subj., 2 Feb. 1962, with enc., “List of Attendees for Bidder’s Conference, Apollo Rendezvous Study,” [2 Feb. 1962]; House Com., Astronautical and Aeronautical Events of 1962, p. 27; D. Brainerd Holmes TWX to all NASA Centers, Attn.: Dirs., 2 March 1962.X

- Shea interview.X

- William E. Lilly, minutes of 2nd meeting of Manned Space Flight Management Council (MSFMC), 6 Feb. 1962, agenda items 2 and 3; Houbolt interview; Shea memo for record, no subj., [ca. 6 Feb. 1962].X

- Charles W. Frick to Robert O. Piland, “Comments on Agenda Items for the Management Council Meeting,” 23 March 1962; MSC Director’s briefing notes for MSFMC meeting, 27 March 1962, agenda item 8; Rector to Johnson, “Meeting with Chance Vought on March 20, 1962, regarding their LEM study,” 21 March 1962; Lilly, minutes of 4th meeting of MSFMC, 27 March 1962.X

- Shea to Rosen, “Minutes of Lunar Orbit Rendezvous Meeting, April 2 and 3, 1962,” 13 April 1962, with enc., Richard J. Hayes, subj. as above, n.d.X

- Frick, interview, Palo Alto, Calif., 26 June 1968.X

- Ibid.; Kehlet, interview, Downey, 26 Jan. 1970; Owen E. Maynard, interview, Houston, 9 Jan. 1970.X

- Frick interview; Rector, interview, Redondo Beach, Calif., 27 Jan. 1970; MSC, “Lunar Orbital Technique for Performing the Lunar Mission,” also known as “Charlie Frick’s Road Show,” April 1962.X

- Low to Shea, “Lunar Landing Briefing for Associate Administrator,” 16 May 1962; Holmes to Shea, NASA Hq. routing slip, 16 May 1962.X

- House Committee on Appropriations’ Subcommittee, Independent Offices Appropriations for 1963: Hearings, pt. 3, 87th Cong., 2nd sess., 1962, p. 571.X

- House Committee on Science and Astronautics, Subcommittee on Manned Space Flight, 1963 NASA Authorization: Hearings on H.R. 10100 (Superseded by H.R. 11737), 87th Cong., 2nd sess., 1962, pp. 528-29, 810.X

- Shea memo for record, no subj., 1 May 1962; Clyde B. Bothmer, minutes of OMSF Staff Meeting, 1 May 1962; Shea memo [for file], no subj., 7 May 1962, with enc., “Direct Flight Schedule Study for Project Apollo: Statement of Work,” 26 April 1962.X

- Harold Hornby, interview, Ames, 28 June 1971; Alfred J. Eggers, Jr., interview, Washington, 22 May 1970; Hornby, “Least Fuel, Least Energy and Salvo Rendezvous,” paper presented at the ARS/IRE 15th Annual Spring Technical Conference, Cincinnati, Ohio, 12-13 April 1961; Hornby, “Return Launch and Re-Entry Vehicle,” in C. T. Leondes and R. W. Vance, eds., Lunar Mission and Exploration (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1964), pp. 588-622.X

- [Bothmer], minutes of NASA OMSF Staff Meeting, 11 May 1962; Holmes to Dirs., LOC, MSC, and MSFC, “The Manned Lunar Landing Program,” 25 May 1962.X

- Shea interview.X

- Ibid.X

- Ibid.; Holmes, interview, Waltham, Mass., 18 Feb. 1969.X

- Remarks on internal rivalries among NASA field centers are based largely on Apollo oral history interviews and on the minutes of the OMSF weekly staff meetings, 1961-1963, with Bothmer as secretary.X

- Bothmer, minutes of MSFMC meeting, 29 May 1962, p. 6.X

- Charles W. Mathews to Dir., MSC, “Background Material for Use in May 29 Meeting of Management Council,” 25 May 1962.X

- Agenda, Presentation to Shea, Office of Systems, OMSF, NASA Hq., on MSFC Mode Studies for Lunar Missions, 7 June 1962; Shea interview.X

- Von Braun, “Concluding Remarks by Dr. Wernher von Braun about Mode Selection for the Lunar Landing Program, Given to Dr. Joseph F. Shea, Deputy Director (Systems), Office of Manned Space Flight, June 7, 1962” (emphasis in original).X

- Shea interview.X

- Bothmer, minutes of OMSF Staff Meeting, 8 June 1962; Hayes to Shea, “LOR briefings by Grumman, Chance-Vought and Douglas,” 12 June 1962.X

- NASA OMSF, “Manned Lunar Landing Program Mode Comparison,” 16 June 1962; addenda to “Manned Lunar Landing Program Mode Comparison,” 23 June 1962.X

- NASA OMSF, “Manned Lunar Landing Program Mode Comparison,” 30 July 1962.X

- Shea interview; Bothmer, minutes of 7th MSFMC meeting, 22 June 1962, pp. 2-3.X

- Seamans, interview, Washington, 11 July 1969.X

- Shea interview; Bothmer, OMSF Staff Meeting, 29 June 1962.X

- NASA, “NASA Outlines Apollo Plans,” news release, 11 July 1962; President’s Science Advisory Council panel, “Report of the Space Vehicle Panel,” 3 Jan. 1962; Markley to Mgr. and Dep. Mgr., ASPO, “Trip report . . . to D.C. on 27 April 1962,” 28 April 1962; Franklyn W. Phillips to Holmes et al., “Request for Contractor’s Reports on Major NASA Projects,” 22 May 1962; Bothmer, 7th MSFMC meeting, p. 5; Bothmer, OMSF staff Meeting, 29 June 1962.X

- Seamans to Dir., OMSF, “Recommendations of the Office of Manned Space Flight and the Management Council concerning the prime mission mode for manned lunar exploration,” 10 July 1962. Gilruth wanted the Saturn C-1B (consisting of the C-1 booster and the S-IVB stage) for development testing and qualification of the command and service modules. The C-1 did not have the capability, and the C-V would be too expensive for such a mission. Frick to NASA Hq., Attn.: Holmes, “Recommendation that the S-IVB stage be phased into the C-1 program for Apollo earth orbital missions,” 23 Feb. 1962; Gilruth to von Braun, “Saturn C-1B Launch Vehicle,” 5 July 1962.X