CHAPTER 13

THE UNIVERSITIES: ALLIES AND RIVALS TO NASA

For several reasons the universities were important to NASA, particularly to the space science program. First, much of the research embraced by space science-such as astronomy, relativity and cosmology, atmospheric studies, and lunar and planetary science-was done in or in conjunction with universities. As a consequence the best informed and most competent researchers important to space science were to be found on campus. While many of the investigators would have to spend long hard hours learning to use the new rocket and spacecraft tools, their years of working with the problems to be solved would give them a substantial head start.

Second, the university was the only institution devoted extensively to the training of new talent. As the space program was getting under way, various groups outside of NASA expressed concern that the new endeavor would lure scientific and technical expertise away from other areas of more immediate national concern. NASA managers argued that many researchers entering the space program would continue their ongoing research, except that now they could apply powerful space techniques to their investigations. In space science the argument was easy to make. Astronomers, would continue to do astronomy, and solar physicists would continue to study the sun, but with the inestimable advantage of having their instruments above the atmosphere, which hitherto had hidden most of the wavelength spectrum from the observer on the ground. Atmospheric and ionospheric researchers would continue their investigations, but having their instruments in the very regions of study would shorten considerably the long chains of reasoning previously needed to go from ground-based observations to conclusions. And sending instruments to the moon and planets would furnish new data, the lack of which had for decades stymied efforts to understand these bodies.

But in applications and technology, the argument was not as persuasive. While one might grant that satellites should contribute to the observation and forecasting of weather and to the improvement of long-distance communications, still there was the usual feeling that conventional approaches needed the more immediate attention. As to the usefulness of space technology, the connection was even less direct and the value of diverting manpower to space technology research more doubtful.

A significant effect of the Soviet Union’s precedence in space was to set aside such arguments for a number of years. But those arguments were bound to recur unless steps were taken to counter any imbalances the space program might generate through the absorption of highly trained manpower from other activities. As a remedy, NASA undertook to support the universities in training substantial numbers of graduates in science and engineering, and even in aspects of law and economics related to space.

In providing support to the universities for research and the training of graduate students, NASA created a staunch ally. For space science especially, as the agency sought to bring university experts into planning the program as well as into the research, relations became quite intimate. But by simultaneously establishing space science groups of its own at NASA centers, NASA generated a substantial strain on the growing tie with the universities. For it was inevitable that the NASA space science groups would appear to have the inside track to funding and space on NASA’s rockets and spacecraft.

Although in time NASA space science groups came to be seen by outside scientists as important points of contact, university researchers continued to worry that, in the face of budget cuts, the continuity of NASA space science teams would be ensured while university groups would be in jeopardy, and that university projects would be more likely to suffer from whims of NASA administrators than would those in the centers. Thus, while the alliance between NASA and the universities strengthened as the program unfolded, the element of rivalry was also there, a rivalry that at times displayed hues of outright antagonism when hard decisions had to be made-like the cancellation of the Advanced Orbiting Solar Observatory, which terminated important university research projects. It was a classic example of a love-hate relationship in which mutual interests and respect conflicted with a natural competition for support and position. For space science, at least, this element of ally and rival must be kept in mind as an important feature of the NASA university program.

The program itself got off to a slow start. NASA inherited little in the way of a university program from the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. Oriented primarily toward in-house research, NASA’s predecessor supported only a limited amount of university research.1 At first NASA’s relations with the university community assumed an administrative complexion and during Glennan’s years the group responsible for handling university matters remained on the administrative side of the house. When Administrator James E. Webb took over, the Office of Grants and Research Contracts, which had prime responsibility for NASA’s university affairs, was still under Albert Siepert, NASA’s director of administration.2

Only gradually did the idea of a university program as such emerge. From the provisions of Public Law 85-934, which went into effect in the fall of 1958, NASA acquired the authority to make grants in support of research pertinent to the NASA mission.3 But for a time NASA did not have the authority to provide for building research facilities on campuses. In May 1959, when Glenn Seaborg, Edward Teller, and some of their colleagues from the University of California at Berkeley met with Hugh Dryden and the author seeking funds to construct a building to house a space institute, Dryden had to tell them that NASA lacked authority to provide such support. The agency was, however, seeking to remedy this situation in the authorization request then before the Congress.4 But, not until the summer of 1961 did the agency gain the legal basis for making facilities grants to universities.5 In spite of its slowness, NASA in its first two years laid the basis for what might be called a conventional program to support space research on university campuses. Webb, the second administrator of NASA, added some decidedly unconventional elements to the program.

STEPPING UP THE PACE

To meet NASA’s own needs, and under prodding from Lloyd Berkner and the Space Science Board, NASA space science managers during 1959 and 1960 gradually evolved a program for support of space science in the universities. By the fall of 1960, a policy for the program had taken shape. In November 1960 the author set forth some elements of policy to be followed with universities and nonprofit organizations. NASA would support basic research in these institutions for the purpose of developing space science, but could not support science in general. NASA would use multiyear funding and would seek to provide continuity of support to academic research groups.6 With these thoughts the shape of the conventional part of the university program was beginning to emerge. It remained to match the size of the program to the need.

During the spring of 1961 the determination grew to strengthen NASA’s association with the universities. Meeting with his staff on 22 June 1961, Webb decided that NASA must encourage university participation in the space program and, moreover, must share in the necessary funding to make it possible for universities to take part. Webb assigned the author the task of organizing an intra-NASA study of how to proceed and to assemble an outside group of consultants. The very next day the author and his associates began to develop a list of topics to take up in the proposed studies, such as support of research, the differing requirements of laboratory research versus spaceflight research, the development of graduate education, the development of schools, the use of grants as opposed to contracts, fellowships, and the construction of facilities on campuses.7 Simultaneously a panel of university presidents, deans, and department heads (app. H) was lined up to meet on 14 August 1961 on the questions NASA posed and other questions that they themselves might bring forward.

On 30 June the author chaired a meeting of representatives from interested offices in the agency to review plans for the meeting.8 A number of the university consultants came to NASA Headquarters in early July for a preliminary look at the questions to be taken up in the August session. Thus, by the time of the meeting, considerable thought had already been devoted to the problems of concern.

At the August meeting, to set the stage for the discussion, Richard Bolt of the National Science Foundation presented some statistics on basic research in universities. Total basic research in the United States, he said, amounted to $1.8 billion annually, of which half was spent in universities. The government provided two-thirds of the university share $600 million. According to Bolt, universities direly needed money to build new facilities, with an immediate requirement of $500 million and a total over the next 10 years of $2.8 billion.9 It was certainly not NASA’s responsibility to provide these huge sums, but any funding would help to relieve the total problem.

Predictably the advisory committee recommended that NASA enhance its university program, providing money for research, graduate training, and construction of new laboratories. With the committee’s welcome endorsement, NASA stepped up the pace of its program. Much of the research supported in universities was funded by the various program offices. Although in the long run such funding proved to be more stable than that from the university office itself, university officials saw serious shortcomings in this procedure. NASA program managers naturally tied their dollar support to specific projects with prescribed objectives, and with firm deadlines for flight experiments. For researchers engaged in such projects, the funding was essential and the imposed requirements unexceptionable. But the question remained of how advanced work, the exploratory research that was needed before an investigator could propose a flight experiment, would be supported.

Out of the need to do advance work grew the concept of the sustaining university program. This terminology was never much liked either in NASA or on the Hill, since it seemed to denote a program to sustain the universities, which was not NASA’s legitimate business. But no better language was devised to describe that part of the university program that was designed to make possible university participation in spaceflight research. For example, the sustaining university program would provide long-term funding of a rather broad nature that would permit the university to build up and maintain a continuing research group and to pursue the ground-based research prerequisite to spaceflight investigations. The broad-based support was achieved by funding research in very general areas pertinent to space sciences, leaving the choice of specific research problems and the setting of schedules largely to the investigator himself.

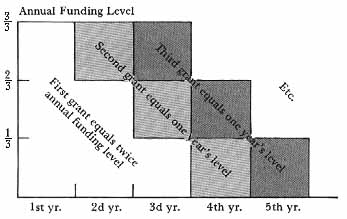

Continuity of support was achieved by step funding.10 At the initiation of a grant, two years’ funding was committed, one full year’s worth to be applied to the first year, two-thirds of a year’s worth assigned to the second year, and the remaining one-third of a year’s funding to be used in the third year (fig. 44). Each year thereafter adding a full year’s funding would continue the arrangement for the next three years. Thus, if at any time NASA had to, or chose to, discontinue the grant, enough money and time would remain so that the work could be phased out in an orderly and rational way-or perhaps support found from some other source. The program offices were also encouraged to use step funding whenever they could see their way clear to do so.

Mindful of the criticism that NASA was using persons critically needed elsewhere, the agency put together a program to fund the training of graduate students in areas related to the space program. During 1962, as NASA managers were trying to determine how large a training program to support, the so-called Gilliland report on the nation’s need for scientific and technical people was in preparation. Although the report did not appear until December 1962, many of its conclusions were widely known well before that time and had a decided impact on NASA’s planning. The report stated that to meet the nation’s needs, the country would have to double by 1970 its production of engineers, mathematicians, and physicists.11 This equated to adding about 4000 persons at the doctorate level to the work force each year. Comparing its total budget with those of sister agencies like the Department of Defense, the National Science Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health, NASA arbitrarily adopted one-fourth of the goal as its fair share. Finding itself unable to meet this goal, the university office ultimately aimed at a steady-state level of 1000 trainees in its program.12 Before many years had passed NASA trainees could be found in universities and colleges of almost every state in the Union. This geographical spread in the program earned the agency considerable praise from members of Congress, although one or two legislators held that NASA had exceeded its authority in entering upon any such training program. By leaving the administration of the training program, including the selection of trainees and their research projects, to the universities-NASA’s prime requirement was that the research be clearly related to space the agency also earned the appreciation of the universities.

Step funding. At the start, two years’ funding was assigned, of which one year’s worth was allocated to the first year, two-thirds of a year’s worth to the second year, and one-third of a year’s worth to the third year. At each annual renewal, one year’s funding allocated in thirds to the next three years restored the original funding status for another three years.

A most important aspect of the sustaining university program was building laboratories for universities interested in the space program. The magnitude of the national need for new university construction had been indicated in Bolt’s brief resume for NASA’s ad hoc advisory committee. From all over the country university administrators came to see NASA officials about the possibility of obtaining funds to construct new buildings. As indicated earlier the pilgrimages had begun even before NASA had the necessary authority to help. Always the story was the same. University interest in doing space research was running high, but facilities were already overloaded by other research and by teaching requirements. To take advantage of the opportunities presented by the space program and to help NASA conduct the space science and other space programs, the university required additional facilities and equipment. Out of this need grew the facilities portion of NASA’s sustaining university program.

By the end of Webb’s first year and a half in office, NASA’s university program had begun to take the shape it would display throughout the 1960s: a component supported by the technical program offices and the sustaining university program supported by the Office of Grants and Research Contracts. The former supported research closely connected with specific programs and projects of the agency, while the sustaining program provided funding for graduate training, the construction of facilities, and continuing research in rather broad areas. As the program was expanded, the underlying policy was also firmed up. To the points listed in the author’s memorandum of November 1960, Webb added an important guideline: NASA was to work with universities in such a way as to strengthen them while at the same time getting NASA’s job done. This particular policy of Webb’s, often repeated in conversation and writing, evoked approbation from the Space Science Board’s Ad Hoc Committee on NASA-University Relationships in the spring and summer of 1962.

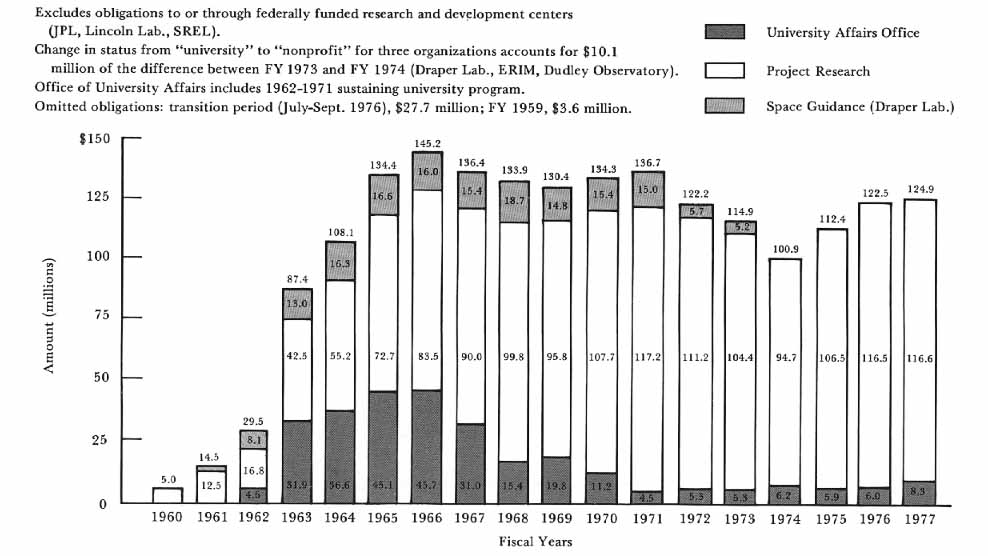

Once launched on a path of renewed growth, the university program increased steadily to more than $100 million a year (fig. 45). The sustaining university program flourished for a number of years before running into peculiar problems that markedly altered its character and greatly reduced its size. To run the program Thomas K. L. Smull had taken over from Lloyd Wood, its initial mentor. Smull, formerly of the NACA, had a broad acquaintance with university administrators and a keen sense not only of the capabilities of universities but also of their needs. He was not an easy conversationalist, and his writing tended to be labored, but these shortcomings were overcome by his imaginativeness and the soundness of his thinking. Because of his obvious interest in the welfare of the universities with which he dealt, a welfare which he put on a par with that of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration which he represented, Smull gained a solid acceptance in the university community.

Funding NASA’s university program. The sustaining program had a special importance; nevertheless, the major part of the funding came from the technical program offices. NASA University Affairs Office, chart P77-158(1), rev. 1, 1978.

To assist in the management of the program Smull brought in a number of key persons. John T. Holloway, a physicist of notably sharp intellect and equally cutting tongue, brought years of experience with universities from the Office of Naval Research and the Office of Defense Research and Engineering. Holloway was effective in promoting all parts of the sustaining university program, and in time became deputy to Smull. Frank Hansing from Agriculture, Donald Holmes from Defense, and John Craig from the Central Intelligence Agency were other new recruits to the office. Almost single-handedly Hansing managed the training grants program, earning the great respect of both colleagues and outsiders. Holmes wrestled in respectable fashion with the more tricky facilities grants, where he encountered a number of vexations not experienced in other parts of the program. Craig took responsibility for the research grants.

Having launched the NASA university program on a career of expansion, Webb continued to give it his personal attention. As part of the reorganization of NASA in the fall of 1961, Webb moved the Office of Grants and Research Contracts from its obscure location in the Office of Administration to the new Office of Space Sciences, where an intimate association with the universities was an important feature of the operating program.13 Following the ad hoc advisory meeting of August 1961, the administrator engaged John C. Honey of the Carnegie Corporation of New York to continue to review and advise on the agency’s program with the universities. While Honey added little to the substantive recommendations of the ad hoc group, he took pains to emphasize that if NASA was serious about elevating the university program, adequate staffing had to be provided. Honey’s judgment was that at the start of 1962 NASA was grossly under-staffed for its projected plans in the university area, and in particular to match the performance of the Office of Naval Research, the National Science Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health in working with universities. For proper effectiveness, Honey advised one manager for each $4 million of program.14 By Honey’s standards, NASA’s university Program was permanently understaffed.

As the program unfolded NASA made a practice of seeking outside evaluations. It was difficult to assess and assimilate such evaluations, for they tended to be highly flavored by the personal views and bents of the evaluators. In June 1964, Sidney G. Roth of New York University turned out a report on NASA-university relations which seemed to show greater concern about how to enhance the benefits of NASA’s program to the universities than about how NASA might get what it needed from the program. It gave much attention to the mechanics of operating the university program. Roth recommended that NASA establish discipline divisions-a biology division, a physics division, etc. -for dealing with universities and make use of corresponding evaluation panels in deciding on grant awards.15 NASA could not use such a recommendation, which failed to take into account the agency’s need to organize along project lines. There just wasn’t a definite sum set aside to go into university research in biology, and another sum for university physics, and so on. Rather, NASA’s monies were earmarked for projects in lunar exploration, satellite astronomy, space communications, and the like. Money was directed into the academic disciplines as they appeared directly or indirectly to support the agency’s assigned projects.

A year later, in a similar study for NASA, D. J. Montgomery of Michigan State University found almost no desire in his widespread discussions to have NASA change its methods of evaluating research proposals.16 A key problem cited by Montgomery was that of communicating adequately to the university community NASA’s intentions and the opportunities NASA could offer for university research.

In 1965 the NASA university program was in full swing.17 The Office of Space Science and Applications was devoting about $30 million a year to the support of university research related to the space science and applications programs, and other program offices were also pouring sizable sums into the universities. In the sustaining university program, the training grants, which now consumed about $25 million a year, had attracted high-caliber students who appeared to be doing good research on important space problems. Twenty-seven research facilities grants had been awarded, and these with the broad research grants were enabling many of the major universities the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Princeton, the University of Wisconsin, and various campuses of the University of California, for example-to establish interdisciplinary space research activities. The sweep of the program and the widespread university interest was brought out in a NASA-university conference held in Kansas City 1-3 March 1965.18 The conference was held to inform the universities of NASA’s plans and to hear university reports of progress in their projects. Those attending comprised a veritable Who’s Who of the university community.19 The meeting evoked both praise and criticism of NASA’s program. Illustrating the praise was a letter from Professor Martin Summerfield of Princeton University.20 Summerfield wrote to compliment NASA both on the conference and on the substance of the NASA university program. He said that he found the same enthusiasm in his talks with colleagues at his university. Most appreciated was NASA’s policy of supporting a university in what the institution found to be in its own self-interest, but the glow of success blinded one to some serious defects. In the sustaining university program were problems that would soon destroy the program as originally conceived, replacing it with one of quite different thrust.

EXPERIMENTAL PROGRAM: FACILITIES GRANTS AND MEMOS OF UNDERSTANDING

When James E. Webb began in the spring of 1961 to encourage NASA managers to expand and deepen the agency’s association with the nation’s universities, they naturally thought in terms of programs like those of the Office of Naval Research or the National Science Foundation, programs which have been characterized here as conventional. But Webb, out of an interest born of his long experience in government as director of the budget and as under secretary of state and many years of association with the Frontiers of Science Foundation in Oklahoma and Educational Services, Inc., in Massachusetts, had more in mind. He wanted to experiment, to create a closer, more fruitful government-university relationship than had existed before.

No sooner had the word gone out that NASA now possessed the authority to support the construction of university facilities and would be receptive to proposals suitably related to the space effort than the agency was deluged with requests for support of laboratories and institutes. The month of October 1961 illustrates the kind of interest that had been stirred up. Lloyd Berkner of the Southwest Research Institute in Dallas obtained from NASA a commitment to support the Institute at the rate of $500 thousand a year on a step-funded basis.21 On 20 October 1961 Nobel Laureate Willard Libby, representing the University of California at Los Angeles, discussed with Webb and the author the possibility of getting money from NASA to erect a building to be devoted to research in the earth sciences. As a site for the building, the university was interested in acquiring title to some neighboring land belonging to the Veterans Administration. The land was understood to be surplus to current government needs, and Libby wondered if NASA might assist in obtaining the real estate for the university.22

Two days later, Governor Kerner of Illinois was in Webb’s office to explore Illinois’s interest in the NASA university program. Immediately on the heels of the discussions with Governor Kerner, James S. MacDonnell, president of MacDonnell Aircraft Company and a trustee of Washington University at Saint Louis, was inquiring as to how Washington University might be related to the space program.23 On 26 October 1961 Professor Gordon MacDonald of UCLA followed up Libby’s earlier Visit seeking an earth-sciences laboratory for the university.24 In these exploratory discussions, Webb’s questioning began to reveal the germ of a new idea, that of getting universities to develop stronger university-community relations.

By 30 October, when Professor Samuel Silver of the University of California visited NASA Headquarters to solicit support for a space science center at Berkeley, Webb’s idea had begun to take shape. Silver needed not only money for space research, but also funds to erect a laboratory to house the space-science center. Webb asked if the proposed center might take on two economists who, working closely with the physicists and engineers, would study the values of science and technology, their feedback into the economy, and how a university can help to solve local problems.25 To Webb the fact that a laboratory provided by NASA would be devoted to space research, while an essential requirement, would not be adequate justification. There had to be more, and during the first half of 1962 the desired quid pro quo was worked out. Following the administrator’s lead, on 3 July 1962 Donald Holmes set down a few notes on the policy that would be followed by NASA in making construction grants to universities. Holmes noted that in accordance with Public Law 87-98, and when the university had met criteria established by NASA, it would be NASA’s intention to vest title in the grantee to the facilities acquired under the facilities grant program.26 Among the criteria would be Webb’s special requirement, of which, in connection with a proposed facility grant to the University of California at Berkeley, Webb wrote on 25 July 1962: "One of the conditions of the facility grant will be to require that each university devote appropriate effort toward finding ways and means to assist its service area or region in utilizing for its own progress the knowledge, processes, or specific applications arising from the space program.” He further stated that a memorandum of understanding signed by senior officials of the university and NASA would be used to establish the conditions of the facility grant.27

These additional conditions for obtaining a facility grant from NASA may or may not have been necessary to justify the grants to Congress, but for Webb they were entirely in character. He repeatedly said that he liked to accomplish several things at once with any action he took. He saw in the universities not only a source of support for the scientific and technical research of NASA, but also the possibility of meeting a much broader need of the administration. In the last half of the 20th century, political, economic, and social problems had become so complex as to place them beyond the comprehension of any single individual or group. As never before in the history of man, statesmen needed advice and counsel based on the expertise, experience, and insight of many diverse talents. Where better to look for this than on the university campus where all kinds of talents and interests exist together, engaged in study and thought at the very frontier of knowledge and understanding? The task was to bring all this talent together in such a way as to derive from it practical and timely advice to administrators and lawmakers.

So, as NASA people sought specific help from the universities in their individual projects and programs, Webb sought to give this developing university program a broader and deeper character. He would support the training of large numbers of graduate students and the construction of limited numbers of buildings for space science and engineering and the aeronautical sciences if university administrations in return would commit themselves to developing new and better ways of working with local governments and industry to solve common problems and advance the general welfare. Webb was especially interested in seeing what could be done to develop readily tappable centers of advice for local, state, and national government.

The universities were quite ready to sign agreements along the lines that Webb desired, but actually showed little understanding of what Webb was talking about. Most university administrators seemed to feel that the agreements were purely cosmetic showpieces that could be used in Congress to justify the construction grants and other subventions to the universities. A few produced some results, but nothing approaching what Webb had hoped for.

Webb’s dream was a desirable objective, but may have been impossible of achievement in the university environment. The independence of the individual researcher, which academic tradition guarantees, fosters the expertise and specialized knowledge that Webb wished to tap. To place such expertise and knowledge on ready call to be applied on command to problems of someone else’s choosing that is, on demand from the government seeking advice, or the university administration seeking to serve the government-would destroy the very independence that generated the unique expertise in the first place. This meant that one would have to rely on voluntary contributions to the activity by individual professors, which left the university administrators in a position of attempting to persuade their professors to join an undertaking the administrators themselves did not understand well enough to describe in very persuasive terms.

To add to the dilemma, university researchers often feel that their best personal contributions to society are to be made through their personal research, which is the thing that they do best. Thus, when Webb asked individual department members if they didn’t feel an obligation to their university administration to help carry out a memorandum of agreement like those with NASA, the answer was no. Such an answer, which was regarded as natural and proper by the university researcher, seemed outrageously callous and irresponsible to Webb.

That NASA could apply only a few tens of millions of dollars in the university area afforded Webb very little leverage. As Richard Bolt of the Science Foundation had pointed out, university needs nationwide for buildings, equipment, and other capital investments were variously estimated in the vicinity of several billions of dollars, against which NASA’s few millions made little showing.

The fortunes of the sustaining university program rode the wave of Webb’s interest in drawing the universities into the broader role in political, economic, and social matters to which he felt they could contribute so much. One may argue over whether Webb’s objectives were achievable at all; but they could hardly have been realized in the few years that he allowed for their accomplishment. In 1965, when the university program appeared to be riding high, Webb, instead of taking satisfaction in its accomplishments, began to show disappointment in its shortcomings. On 19 February 1965 he wrote to the author that "no university, even under the impetus of the facilities grant accompanied by a Memorandum of Understanding, had found a way to do research or experiment with how the total resources of the university could be applied to specific research projects insofar as they are applicable.”28

Webb met frequently with university heads to press them for reports of progress. He asked for independent reviews of the program. One of these conducted by Chancellor Hermann Wells of the University of Indiana, included an extensive tour of the universities owning buildings paid for by NASA. The report did not give Webb the encouragement he sought. When the president of one of the universities Webb felt most likely to produce good results stated that most of the universities believed Webb had introduced the memo of understanding purely to satisfy Congress and that he really wasn’t serious about requiring performance under the agreement, the administrator’s disenchantment was complete. As 1966 rolled around it became clear to his associates that Administrator Webb was planning to wind down the sustaining university program.

In an effort to forestall any such curtailment, the author wrote a 13-page memorandum to the administrator pointing out the importance of the universities, the substantial accomplishments already achieved in the NASA university program, the highly successful training-grant program which was already bringing many competent young recruits into the space program, and the increasing flow of results from the research grants.29 The author argued for a strong, continuing program, emphasizing that current accomplishments were the results of steps taken many years before and that a successful program of the kind NASA now had was the best possible basis from which to try to achieve the special objectives Webb had in mind. It was too late; events had overtaken the program. Added to Webb’s disappointment with lack of performance on the memoranda of understanding was an emergent suspicion that the Gilliland Committee report might have grossly overestimated the need for new technical people in the nation’s work force. Physicists and engineers, especially in the aerospace field, were beginning to have difficulty in landing jobs, and it was just possible that NASA’s sizable graduate-training program might be exacerbating a serious national problem. Simultaneously President Johnson, disturbed by unrest and violence on the campus and smarting from what he regarded as gross ingratitude for all that his administration had done to help students pursue their education, was disinclined to provide any further assistance. (That the dissidents were associated with departments other than the scientific and technical ones with which NASA was concerned was obscured by the emotions of the period.) As Webb later told the author, he had been instructed by the president-in a memorable meeting-to wind down the training program. In the existing climate, Webb proceeded to phase out the facilities grant program also. This dropped the sustaining university program to about one-quarter its previous level by FY 1968, for the time being consisting principally of the broad area-research grants. Numerous congressmen, like Joseph Karth of Minnesota, who had found the sustaining university program to their liking, expressed disapproval when the new budget requests showed how much it was being curtailed. Nevertheless, the cuts stood.

Ultimately Smull and Holloway became casualties of Webb’s disillusionment over the NASA university program. To Smull and Holloway-and to the author also-the basic university program was amply justified by the important, often essential, contributions made to the prime NASA objectives in space science and technology. Webb’s desire for a broader government-university relationship, while understandable and laudable, seemed best regarded as a hope for an additional benefit that might or might not be attained.

But Webb didn’t see it that way. To him the broader objectives were the most significant contribution that the university program, or at any rate the sustaining university program, could make. Without that contribution the program forfeited his endorsement. He came to feel that Smull and Holloway favored the conventional program too much and did not put enough effort into achieving the newer relationships he sought. From accompanying Smull on numerous visits to universities and hearing him urge on university people Webb’s desire for performance under the memos of understanding, the author knows that the administrator was wrong in this estimate. But the lack of mutual understanding grew, exacerbated by Holloway’s sharp tongue and Smull’s failure to display to the universities the image of NASA that Webb desired. Finally Holloway left to take a position in another agency. Smull moved to another office in NASA.

Francis Smith, an electronics engineer from the Langley Research Center who had achieved considerable success in conducting various investigations and planning activities for NASA, was put in charge. Phoenix-like, out of the ashes the Office of Grants and Research Contracts rose again in form of an Office of University Affairs, for a short while reporting directly to the administrator and then for a number of years to the associate administrator. Honest, witty, and bedeviled by Webb’s assignments to duties he really didn’t care for, Smith nevertheless displayed a willingness to experiment that put him in great favor with the administrator. But Smith did not long stay at the post, leaving NASA to go to the University of Houston. Thereafter Frank Hansing took over and proceeded to mold the university program to the needs of NASA as perceived by top management.

EXPERIMENTAL PROGRAM: RESEARCH INSTITUTES

NASA’s evident willingness to experiment with new relationships and management devices antedated Webb’s administration. In this a prime mover with regard to academic ties was Robert Jastrow, a physicist who had come to NASA from the Naval Research Laboratory in November 1958. An imaginative theorist, Jastrow over his years with NASA interested himself in atmospheric and magnetospheric physics, meteorology and atmospheric predictability, the origin of the moon and planets, and astrophysics and cosmology. He was a superb speaker, able to hold both lay audiences and professional colleagues spellbound with his descriptions of space science topics, an ability that served NASA well when Jastrow appeared before congressional committees in defense of the agency’s space science budget request. He produced numerous books and articles of both technical and popular level.30 On television he was a frequent exponent of the many benefits mankind was receiving from the space program.

Immediately upon joining NASA Jastrow busied himself with promoting space science. He joined forces with Harold Urey to agitate for an early start of a lunar program. But Jastrow was also convinced that the best minds could be attracted into the space program only if the agency could establish the right atmosphere in dealing with university researchers. He set about trying to establish such an atmosphere.

In December 1958 Jastrow suggested to Administrator Glennan the establishment of a NASA fellowships program to be administered by the National Research Council of the Academy of Sciences.31 Jastrow urged that the fellowship provide a large enough stipend that a post-doctoral researcher could afford to take advantage of it. The fellow would come to NASA to work on a problem of his own choosing, NASA’s only requirement being that the problem be pertinent to space. Having the program operated by the National Research Council might free it, in the minds of prospective fellows, from the taint of bureaucratic bias and parochialism. The suggestion was approved, and a formal announcement of the program appeared the following March.32

The program attracted national and international interest and brought many first-rate researchers to NASA. From the Goddard Space Flight Center, where it started, the fellowship program spread to other NASA centers including the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.33 In this way NASA developed an association with hundreds of competent scientists throughout the United States and the rest of the world, and these scientists became personally interested in space research.

Jastrow soon came to feel that continuous attention to the theoretical basis for space investigations wits essential to a sound and productive program. He therefore joined the newly formed Goddard Space Flight Center, where he took on the task of assembling what eventually became the Theoretical Division of the center. Still not satisfied with this setup, because it lacked the drawing power to attract the best minds, Jastrow then proposed that a small study group be in a location more easily accessible to visiting scientists. He chose a set of offices in the Mazor Building in Silver Spring, Maryland, which was not too difficult to get to from downtown Washington or the National Airport. Here, supported with contracted computing capabilities, he initiated what was to become one of the most interesting experiments in government relations with the scientific community and academia. Visiting researchers were welcomed to work on space science problems, and such luminaries as Gordon MacDonald, a leading geophysicist, and Harold Urey, lunar and planetary expert, came. MacDonald remained for more than a year. Leading experts from around the world were invited to frequent work sessions on important space science topics, like particles and fields in space, the solar system, and cosmology. Presentations treated the most advanced aspects of their fields and were thoroughly discussed by the attendees. These sessions and the ongoing work of Jastrow’s group were the source of numerous ideas for space science experiments.

An important element of Jastrow’s concept was close working relations with local universities, for teaching and working with doctoral students was considered one of the best ways to keep a researcher on his toes and was one of the best stimuli imaginable for generating research ideas. In this respect Jastrow found the Washington area deficient. Although good relations were established with the University of Maryland, Catholic University, and others, still the quality of their contributions was not up to what Jastrow sought. In October 1960 Jastrow wrote to Abe Silverstein head of the Office of Space Flight Programs, which housed the space science office-proposing that NASA create a center for theoretical research. By 13 December the proposal had evolved into one to establish an Institute for Space Studies in New York City, where close relations could be developed with leading universities like Columbia, New York University, and Princeton. With support from both Silverstein and the author, Glennan quickly approved the proposal.34

Whether the Institute should become an independent center or remain part of the Goddard Space Flight Center was seriously discussed. In the end, the tremendous obstacles that would stand in the way of creating another new NASA center, and the uncertainty that in the face of political jockeying NASA could sustain the choice of New York City for its location, led to abandoning the notion of a separate center. The Institute for Space Studies was set up in New York, in rented quarters, as an arm of the Goddard Space Flight Center, but with considerable autonomy over the choice of its research activities.35

The permanent staff was intentionally small, a half-dozen key researchers plus secretarial and administrative help. Most of the researchers on site were to be visiting experts who would spend from a few weeks to as much as a year at a time at the institute working on space science problems and joining in the discussions of the frequent work sessions. A large computer was rented with programming staff, and later purchased. As time went on the computing capability was enlarged and improved, giving the institute one of its most attractive features.

Among those who came to the institute for extended stays were the ubiquitous Harold Urey, who seemed to turn up wherever exciting space topics were being pursued; H. C. van de Hulst, astronomer, solar physicist, and first president of the international Committee on Space Research; and W. Priester, pioneer worker in high atmospheric structure, who did much to determine seasonal and other variations in upper air densities.

In New York it was possible to arrange the kinds of university faculty appointments needed to give the institute the desired academic ties. Visiting professors lectured at the institute. Institute members taught at Columbia and other universities and became faculty advisers to doctoral candidates working on space science topics. With contracts the institute gave several hundred thousand dollars worth of funding support annually to university research of mutual interest. Through these associations the institute became a unique experiment in government-university relationships.

Among the early areas of interest at the Goddard Institute for Space Studies were lunar and planetary research, the origin of the solar system, and astrophysics and cosmology. Studies of energy balance in the earth’s atmosphere occupied a great deal of attention, and later considerable work was done on predictability in the earth’s atmosphere, a topic central to making long-term forecasts of weather and climate. When the exciting possibilities of infrared astronomy became apparent, the institute, although predominantly devoted to theoretical research, set up a small experimental activity alongside the theoretical work.36

Papers flowed into the journals. Many of the work sessions gave rise to books on frontier topics, like Jastrow’s Origin of the Solar System.37 A. W. Cameron published prodigiously on theoretical investigations into the origins of the solar system, stars, and other celestial objects.

The Goddard Institute gave NASA a firm connection with a number of important universities and with a broad spectrum of working scientists; but key members of what one often referred to as the scientific establishment remained aloof, apparently not hostile so much as indifferent. So Jastrow proposed still another experiment, a meeting of top NASA people with foremost leaders of the scientific community. On 20-21 June 1963, at Airlie House near Warrenton, Virginia, James Webb, Hugh Dryden, Harry Goett, and the author listened as Jastrow, Gordon MacDonald, and others presented to the elite of physics in the United States (app. I) an exciting review of the kinds of problems that could now be attacked with rockets and spacecraft. An interest was aroused, and the group agreed to meet periodically to keep in touch with the space program. Formally designated as the Physics Committee, the group operated more as a colloquium than as the usual advisory committee. Robert Dicke of Princeton, expert on relativity and cosmology, became its first chairman.38 Some of the most exciting experiments for the NASA space science program-in such areas as x-ray astronomy, relativity, and cosmology-were on the bill of fare. As time went on ideas from the many discussions found their way into the flight program of the agency. One may cite as examples Bruno Rossi’s work on high-energy astronomy, the work of Stanford University on the relativistic precession of accurate gyroscopes in orbit, and the corner reflectors; implanted on the moon by the Apollo astronauts to support precise geodetic measurements.

With the NASA fellowship program, the establishment of the Goddard Institute for Space Studies, and the formation of the NASA Physics Committee, Jastrow had contributed immeasurably to providing NASA with a well rounded tie to the university community, particularly in physics and cosmology. Many came to hope that the Goddard Institute could serve as a pattern for other space institutes-for example, in lunar research, planetary studies, and astronomy, as the Ramsey Committee seemed to favor (p. 217). But in the late 1960s conditions were different from those prevailing when the Goddard Institute had been established. Setting aside the question of how much the institute’s success owed to Jastrow’s leadership, special difficulties were encountered. Budgets were rising in the early 1960s, falling in the latter half. The pattern of associations with the newly formed NASA still had to be developed in the early years of the agency, while in the late 1960s working patterns and vested interests had already been established which outside scientists would be loath to disturb. Nevertheless, following the report of the Ramsey Committee, Webb wished to experiment once more, this time introducing a new element, that of the university consortium.

Recognizing that there would be a vast store of lunar samples and other lunar data housed at the Johnson Space Center and that the center would have facilities and equipment needed to analyze and study these data, Administrator Webb desired to evolve some mechanism for facilitating the use of those resources by outside scientists, particularly university researchers. The success of the Goddard Institute for Space Studies suggested that a lunar institute might be set up as an arm of the Johnson Space Center. But the image that the center had acquired of not understanding the needs of science or being particularly interested in science made such an arrangement unattractive to many outside scientists-and also to the Office of Space Science and Applications in NASA Headquarters.

Instead of an institute managed by the center, Webb turned to the possibility that an institute might be managed by a university or a group of universities. Fred Seitz, president of the National Academy of Sciences, showed an interest. An existing consortium, University Research Associates, considered setting up and managing an institute for NASA. The possibility that Rice Institute might either by itself or as one of a number of universities provide the desired link between academia and the resources of the Johnson Space Center was also weighed. In the end a group of universities on 12 March 1969 formed a new consortium called the University Space Research Association and took over management of the Lunar Science Institute, which in its impatience NASA had already set up with the aid of the Academy of Sciences.39 The new institute was housed in a mansion adjacent to the Johnson Space Center, provided by Rice Institute and refurbished by the government. At once the Lunar Science Institute began to hold scientific meetings, invite visitors to use its facilities, and foster lunar research.

The pattern of activities at the Lunar Science Institute was, at least on the face of things, similar to that that had proved so successful with the Goddard Institute for Space Studies, But the LSI at the end of the 1960s faced a number of vicissitudes that the Goddard Institute had not encountered. For example, after 10 years of working with NASA, some academic scientists had already managed to overcome the previously mentioned difficulties to establish personal ties with the Johnson Space Center and did not wish to see a new organization interposed. In contrast foreign scientists who did not have such close associations with the space center found the LSI a boon.

On its part, the Johnson Space Center was ambivalent about LSI. Such an institute could be useful in working with the scientific community, serving as a buffer when difficult issues had to be wrestled with. But when the institute’s managers pressed for an independent research program plus rather free access to such resources as Apollo lunar samples and various lunar data, there was trouble, which occasional personality clashes enhanced.

Most fundamental, however, was the decline of NASA’s budgets in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and a number of times NASA’s space science managers considered withdrawing financial support from the Lunar Science Institute. The Goddard Institute for Space Studies was also beset by similar financial pressures, but its established position in the NASA family made it easier to weather these storms than it was for the Lunar Science Institute, which still had not had enough time to prove itself.

Thus, while the Lunar Science Institute could not be called a failure, its success in the severe climate in which it was launched, was an uneasy one. There could be little question that when time came to consider establishing an astronomy institute in support of an orbiting astronomical facility, or a planetary institute in support of more intensive exploration of the solar system, such propositions would receive long and searching scrutiny before being implemented.

A SLOWER PACE

Following the close-out of the facility grants program and the phasing down of the training grants, the sustaining university program became a low-key operation. It was used to stimulate advanced research in areas important to space applications and to provide seed grants to a large number of minority institutions. There was some experimenting for example-with the development of new engineering curricula in the universities to meet modern needs-but the earlier flair was gone. Always the largest dollar component of the university program, the project grants of the technical program offices became the main thrust of NASA’s university program. But the cutback on the sustaining university program had its impact on the project grants. In space science, for example, more money than before had to be devoted to support of the more advanced research to lay the groundwork for spaceflight experiments, much of which had come out of the graduate research projects of NASA space science trainees. The effect was not easy to measure, but there were tangible signs. Program managers found it more difficult to provide step funding than before, and earlier step funding was often allowed to lapse to gain a year’s funding and thereby ease the current squeeze on the budget. Thus, although the total university program remained in the vicinity of $100 million per year, the more liberal flavor that had ensured a considerable continuity of support and had afforded the universities the ability to plan future staffing and research projects in a rational manner, was gone.

Source Notes

- Alex Roland, Research by Committee. A History of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, NASA SP-4103, comment ed. (Washington, 1979).X

- Jane Van Nimmen and Leonard C. Bruno with Robert L Rosholt, NASA Historical Data Book, 1958-1968, vol. 1. NASA Resources, NASA SP-4012 (Washington, 1976), p. 540.X

- NASA, Office of General Counsel, National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958, As Amended, and Related Legislation (Washington, 1 July 1969). p. 9.X

- Homer E. Newell, rpt. of conference between Glenn Seaborg and colleagues and Hugh Dryden and Newell, 1 May 1959, NF11 (171).X

- Public Law 87-98, 87th Cong., 1st sess., 75 Stat. 216, 21 July 1961.X

- Newell, memo on NASA policy of support of research in universities and nonprofit organizations, 10 Nov. 1960, NF12(176).X

- Author’s notebook, 22 and 23 June 1961, NF28.X

- Newell, conference rpt. on internal NASA meeting to discuss developing NASA-university relationships, 30 June 1961, NF12(177).X

- Author’s notebook, 14 Aug. 1961, NF28.X

- W. A. Greene, "Step Funded Research Grants,” Bioscience 18 (1968):1133-36; F. L. K. Smull, The Nature and Scope of the NASA University Program, NASA SP-73 (Washington, 1965), pp. 11-12; NASA, Office of Grants and Research Contracts Brochure, A Guide to NASA Policies and Procedures for Grants and Research Contracts, Sept. 1965 p. 20: NF19(402).X

- Edwin Gilliland, "Meeting Manpower Needs in Science and Technology,” President’s Science Advisory Committee rpt., 12 Dec. 1962.X

- Smull, NASA University Program, pp. 23-28.X

- Van Nimmen et al., NASA Resources, p. 541.X

- John C. Honey to Newell, 7 Feb. 1962, NF2(41); also author’s notebook. 7 Feb. 1962, NF28.X

- Sidney G. Roth, "A Study of NASA-University Relations,” 30 June 1964, NF2(41).X

- D. J. Montgomery, "A Study of NASA-University Relations,” 30 Nov. 1965, N12(41).X

- Smull, NASA University Program, NF2(41).X

- Summary Report on the NASA-University Program Review Conference, Kansas City, 1-3 March 1965, NASA SP-81 (Washington, 1965), NF18(378).X

- Author’s working file, NF18(378).X

- Martin Summerfield to Newell, 3 May 1965, NF13(200).X

- Author’s notebook, 19 Oct. 1961, NF28.X

- Ibid., 20 Oct. 1961.X

- Ibid., 23 Oct. 1961.X

- Ibid., 26 Oct. 1961.X

- Ibid., 30 Oct. 1961.X

- Donald Holmes, memo to file, 3 July 1962, National Archives Rec. Grp. 255, Acc. 67A601. FRC Box 27 (1/17-51-1).X

- James E. Webb to Newell, 25 July 1962, Rec. Grp. 255, Acc. 67A601, FRC Box 27 (1/17-51-1): Smull, NASA University Program, pp. 36-37. See also Newell to Assoc. Admin., NASA, 23 July 1962.X

- Webb to Newell, 19 Feb. 1965, NF2(41).X

- Newell to Webb. 20 Apr. 1966, NF2(41).X

- See, for example, Robert Jastrow and A. G. W. Cameron, eds., Origin of the Solar System (New York: Academic Press, 1968); Jastrow and Malcolm H. Thompson, Astronomy: Fundamentals and Frontiers (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1972): Jastrow, Red Giants and White Dwarfs (New York: Harper & Row, 1967).X

- Jastrow to T. Keith Glennan. 11 Dec. 1958, NF2(35).X

- Hugh Dryden to Abe Silverstein, 24 Dec. 1958; NASA release, "NASA Announces Research Appointments Program,” 11 Mar. 1959: NF2(35).X

- Newell to Hugh Dryden, 15 Dec. 1959, NF12(173).X

- Jastrow to Silverstein, 14 Oct. 1960, NF2(46); Jastrow to Silverstein, 13 Dec. 1960, NF2(46); Glennan to Silverstein, 14 Dec. 1960. See also Glennan’s approval signature, 4 Jan. 1961, at bottom of supporting memo, Silverstein to Glennan. 3 Jan. 1961, NF2(46).X

- Van Nimmen et al., NASA Resources, p. 284.X

- Ibid., pp. 284-85.X

- Jastrow and Cameron, Origin of the Solar System.X

- Author’s notebook, 20, 21 June 1963, NF28. This committee should not be confused with the Physical Sciences Committee later established under NASA’s Space Program Advisory Council.X

- Weekly compilation of Presidential Documents, week ending Friday, 8 Mar. 1968, pp. 411-12; E. W. Quintrell to B. L. Kropp, 23 Dec. 1968, forwards from NASA to National Academy of Sciences the initial grant beginning 1 Oct. 1968 for operation of Lunar Science Institute by the academy, NASA University Affairs Office records, Lunar Science Institute 1969; Office of Recorder of Deeds, District of Columbia, Certificate of Incorporation of Universities Space Research Association, 12 Mar. 1969, plus attachments; NASA University Affairs Office records, Lunar Science Institute 1969. See also unsigned paper, "History of Lunar Science Institute (LSI) and University Space Research Association (USRA),” July 1971, in NASA University Affairs Office records, Lunar Science Institute, 1969.X