”The Eagle Has Landed"

By MICHAEL COLLINS and EDWIN E. ALDRIN, JR.

Prelude

All was ready. Everything had been done. Projects Mercury and Gemini. Seven years of Project Apollo. The work of more than 300,000 Americans. Six previous unmanned and manned Apollo flights. Planning, testing, analyzing, training. The time had come.

We had a great deal of confidence. We had confidence in our hardware: the Saturn rocket, the command module, and the lunar module. All flight segments had been flown on the earlier Apollo fights with the exception of the descent to and the accent from the Moon’s surface and, of course, the exploration work on the surface. These portions were far from trivial, however, and we had concentrated our training on them. Months of simulation with our colleagues in the Mission Control Center had convinced us that they were ready.

Although confident, we were certainly not overconfident. In research and in exploration, the unexpected is always expected. We were not overly concerned with our safety, but we would not be surprised if a malfunction or an unforeseen occurrence prevented a successful lunar landing.

As we ascended in the elevator to the top of the Saturn on the morning of July 16, 1969, we knew that hundreds of thousands of Americans had given their best effort to give us this chance. Now it was time for us to give our best.

—Neil A. Armstrong

The splashdown May 26, 1969, of Apollo 10 cleared the way for the first formal attempt at a manned lunar landing. Six days before, the Apollo 11 launch vehicle and spacecraft half crawled from the VAB and trundled at 0.9 mph to Pad 39-A. A successful countdown test ending on July 3 showed the readiness of machines, systems, and people. The next launch window (established by lighting conditions at the landing site on Mare Tranquillitatis) opened at 9:32 AM EDT on July 16, 1969. The crew for Apollo 11, all of whom had already flown in space during Gemini, had been intensively training as a team for many months. The following mission account makes use of crew members’ own words, from books written by two of them, supplemented by space-to-ground and press-conference transcripts.

ALDRIN: At breakfast early on the morning of the launch. Dr. Thomas Paine, the Administrator of NASA, told us that concern for our own safety must govern all our actions, and if anything looked wrong we were to abort the mission. He then made a most surprising and unprecedented statement: if we were forced to abort, we would be immediately recycled and assigned to the next landing attempt. What he said and how he said it was very reassuring.

We were up early, ate, and began to suit up - a rather laborious and detailed procedure involving many people, which we would repeat once again, alone, before entering the LM for our lunar landing.

While Mike and Neil were going through the complicated business of being strapped in and connected to the spacecraft’s life-support system, I waited near the elevator on the floor below. I waited alone for fifteen minutes in a sort of serene limbo. As far as I could see there were people and cars lining the beaches and highways. The surf was just beginning to rise out of an azure-blue ocean. I could see the massiveness of the Saturn V rocket below and the magnificent precision of Apollo above. I savored the wait and marked the minutes in my mind as something I would always want to remember.

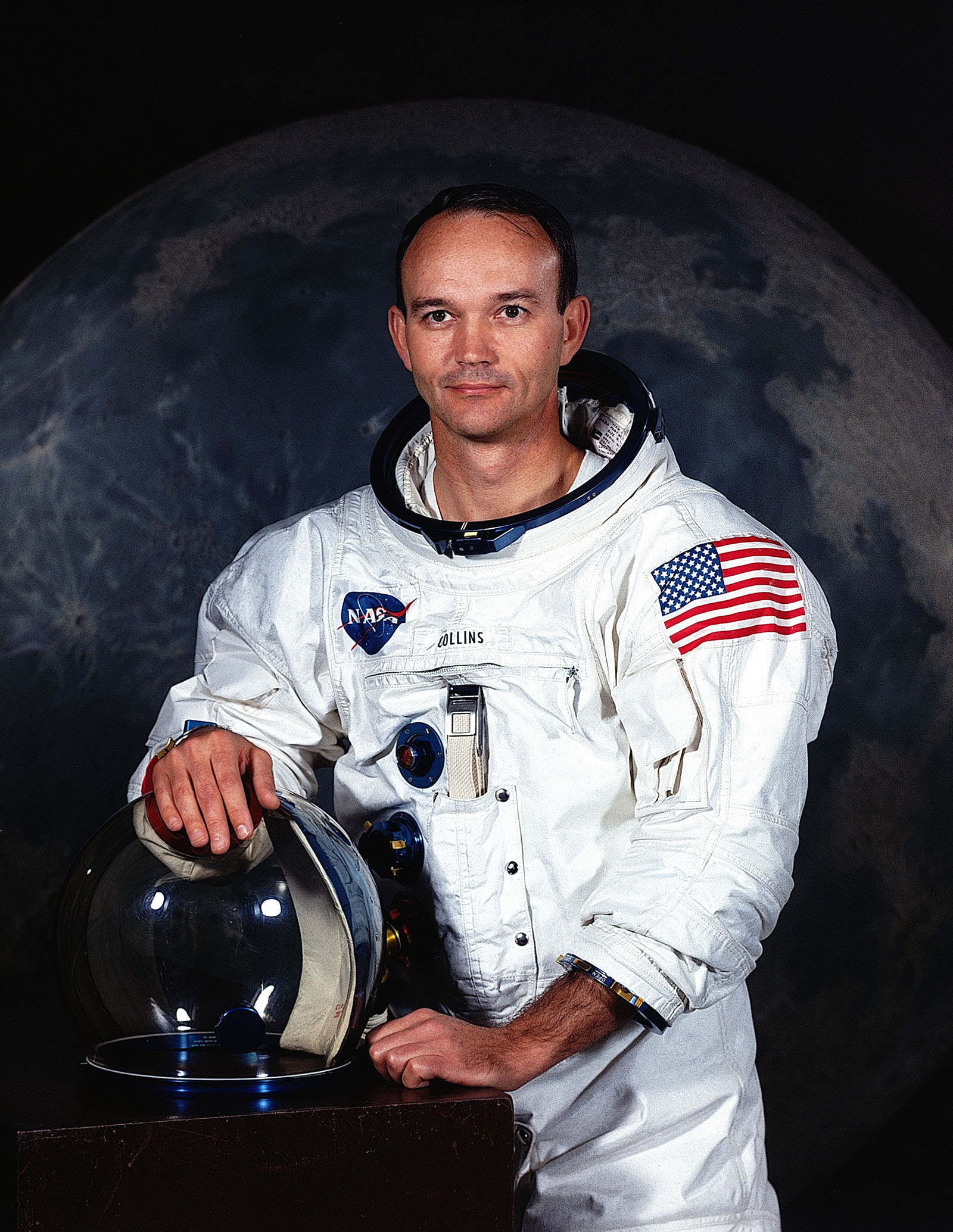

COLLINS: I am everlastingly thankful that I have flown before, and that this period of waiting atop a rocket is nothing new. I am just as tense this time, but the tenseness comes mostly from an appreciation of the enormity of our undertaking rather than from the unfamiliarity of the situation. I am far from certain that we will be able to fly the mission as planned. I think we will escape with our skins, or at least I will escape with mine, but I wouldn’t give better than even odds on a successful landing and return. There arc just too many things that can go wrong. Fred Haise [the backup astronaut who had checked command-module switch positions] has run through a checklist 417 steps long. and I have merely a half dozen minor chores to take care of - nickel and dime stuff. In between switch throws I have plenty of time to think, if not daydream. Here I am, a white male, age thirty-eight, height 5 feet 11 inches, weight 165 pounds, salary $17,000 per annum, resident of a Texas suburb, with black spot on my roses, state of mind unsettled, about to be shot off to the Moon. Yes, to the Moon.

At the moment, the most important control is over on Neil’s side, just outboard of his left knee. It is the abort handle, and now it has power to it, so if Neil rotates it 30 counterclockwise, three solid rockets above us will fire and yank the CM free of the service module and everything below it. It is only to be used in extremes. A large bulky pocket has been added to Neil’s left suit leg, and it looks as though if he moves his leg slightly, it’s going to snag on the abort handle. I quickly point this out to Neil, and he grabs the pocket and pulls it as far over to the inside of his thigh as he can, but it still doesn’t look secure to either one of us. Jesus, I can see the headlines now: “MOONSHOT FALLS INTO OCEAN.” Mistake by crew, program officials intimate. Last transmission from Armstrong prior to leaving the pad reportedly was ‘Oops.’”

ARMSTRONG: The flight started promptly, and I think that was characteristic of all events of the flight. The Saturn gave us one magnificent ride, both in Earth orbit and on a trajectory to the Moon. Our memory of that differs little from the reports you have heard from the previous Saturn V flights.

ALDRIN: For the thousands of people watching along the beaches of Florida and the millions who watched on television, our lift-off was ear shattering. For us there was a slight increase in the amount of background noise, not at all unlike the sort one notices taking off in a commercial airliner, and in less than a minute we were traveling ahead of the speed of sound.

COLLINS: This beast is best felt. Shake, rattle, and roll! We are thrown left and right against our straps in spasmodic little jerks. It is steering like crazy, like a nervous lady driving a wide car down a narrow alley, and I just hope it knows where it’s going, because for the first ten seconds we are perilously close to that umbilical tower.

ALDRIN: A busy eleven minutes later we were in Earth orbit. The Earth didn’t look much different from the way it had during my first flight, and yet I kept looking at it. From space it has an almost benign quality. Intellectually one could realize there were wars underway, but emotionally it was impossible to understand such things. The thought reoccurred that wars are generally fought for territory or are disputes over borders; from space the arbitrary borders established on Earth cannot be seen. After one and a half orbits a preprogrammed sequence fired the Saturn to send us out of Earth orbit and on our way to the Moon.

ARMSTRONG: Hey Houston, Apollo 11. This Saturn gave us a magnificent ride. We have no complaints with any of the three stages on that ride. It was beautiful.

COLLINS: We started the burn at 100 miles altitude, and had reached only 180 at cutoff, but we are climbing like a dingbat. In nine hours, when we are scheduled to make our first midcourse correction, we will be 57,000 miles out. At the instant of shutdown, Buzz recorded our velocity as 35,579 feet per second, more than enough to escape from the Earth’s gravitational field. As we proceed outbound, this number will get smaller and smaller until the tug of the Moon’s gravity exceeds that of the Earth’s and then we will start speeding up again. It’s hard to believe that we are on our way to the Moon, at 1200 miles altitude now, less than three hours after liftoff, and I’ll bet the launch-day crowd down at the Cape is still bumper to bumper, straggling back to the motels and bars.

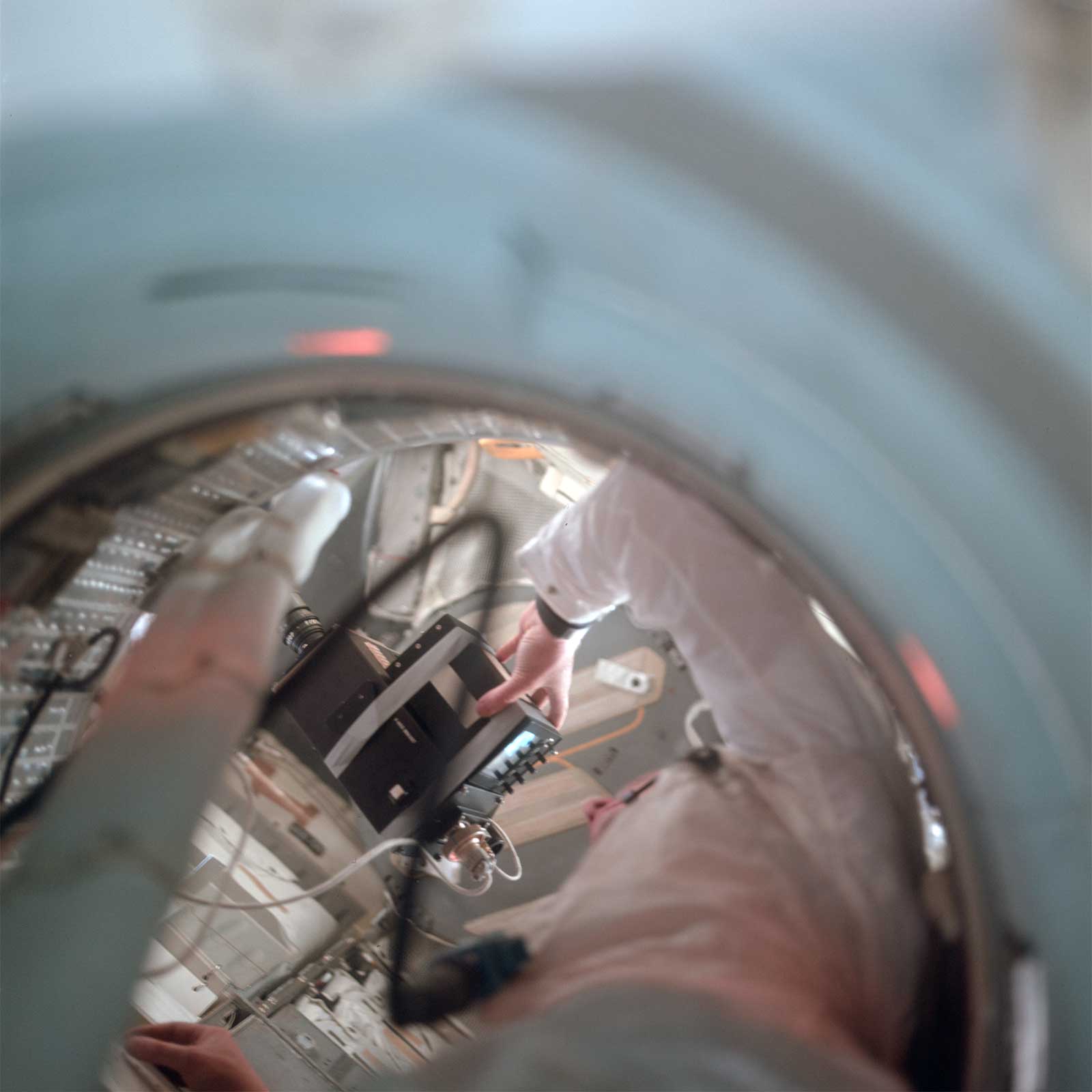

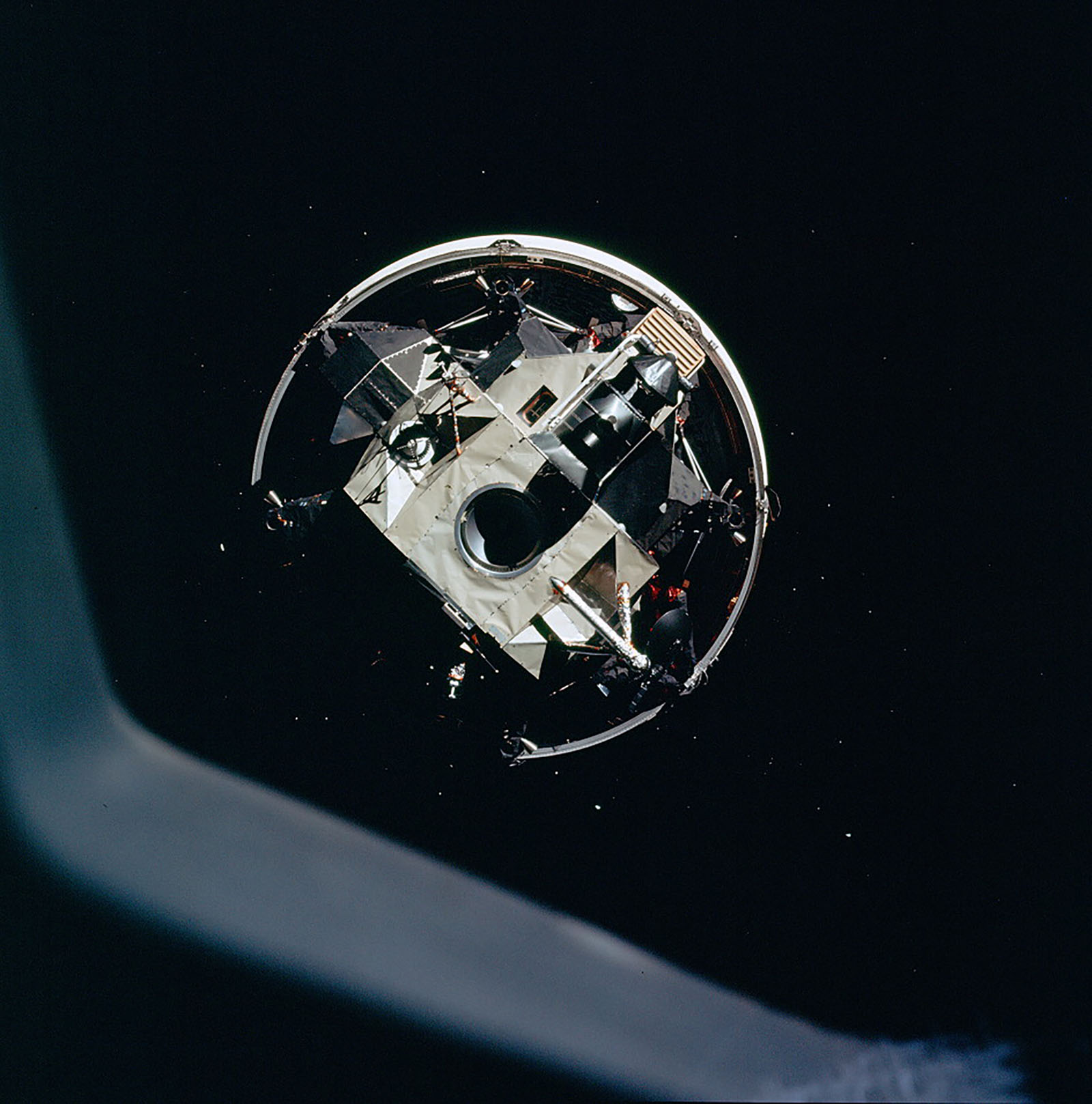

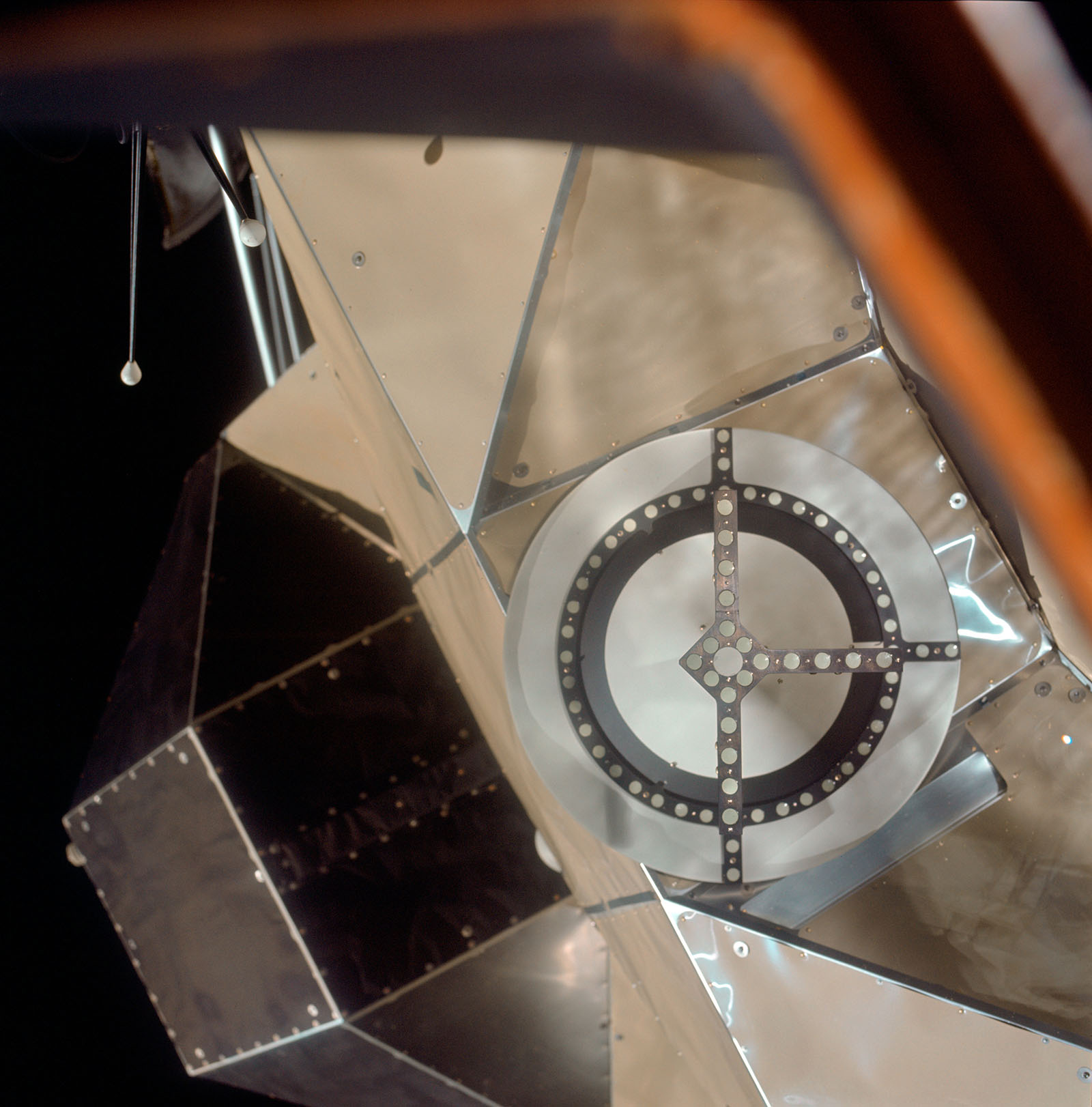

ALDRIN: Mike’s next major task, with Neil and me assisting, was to separate our command module Columbia from the Saturn third stage, turn around and connect with the lunar module Eagle, which was stored in the third stage. Eagle, by now, was exposed; its four enclosing panels had automatically come off and were drifting away. This of course was a critical maneuver in the flight plan. If the separation and docking did not work, we would return to Earth. There was also the possibility of an in-space collision and the subsequent decompression of our cabin, so we were still in our spacesuits as Mike separated us from the Saturn third stage. Critical as the maneuver is, I felt no apprehension about it, and if there was the slightest inkling of concern it disappeared quickly as the entire separation and docking proceeded perfectly to completion. The nose of Columbia was now connected to the top of the Eagle and heading for the Moon as we watched the Saturn third stage venting, a propulsive maneuver causing it to move slowly away from us.

Fourteen hours after liftoff, at 10:30 PM by Houston time, the three astronauts fasten covers over the windows of the slowly rotating command module and go to sleep. Days 2 and 3 are devoted to housekeeping chores, a small midcourse velocity correction, and TV transmissions back to Earth. In one news digest from Houston, the astronauts are amused to hear that Pravda has referred to Armstrong as “the czar of the ship”.

ALDRIN: In our preliminary flight plan I wasn’t scheduled to go to the LM until the next day in lunar orbit, but I had lobbied successfully to go earlier. My strongest argument was that I’d have ample time to make sure that the frail LM and its equipment had suffered no damage during the launch and long trip. By that time neither Neil nor I had been in the LM for about two weeks.

THE MOST AWESOME SPHERE

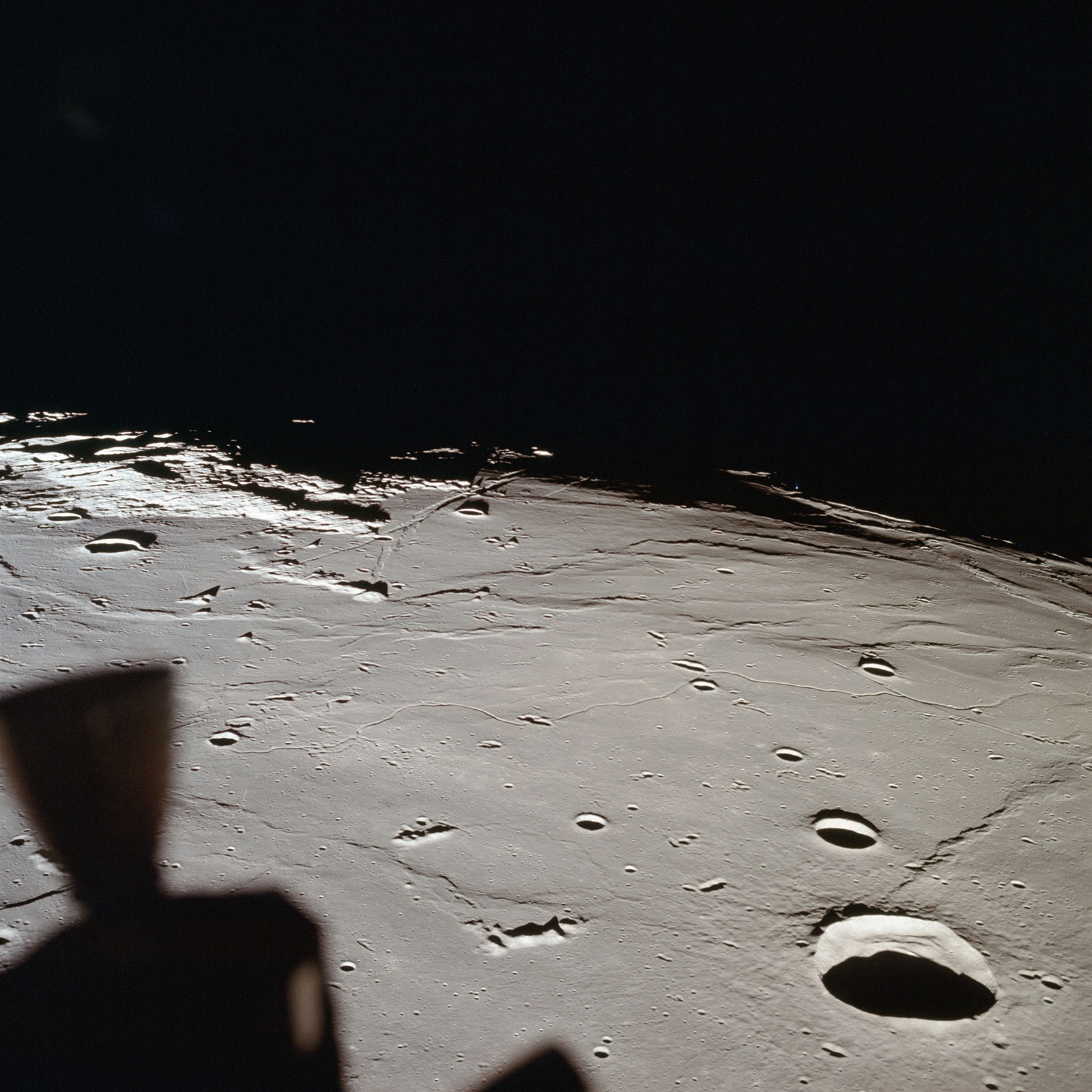

COLLINS: Day 4 has a decidedly different feel to it. Instead of nine hours’ sleep, I get seven - and fitful ones at that. Despite our concentrated effort to conserve our energy on the way to the Moon, the pressure is overtaking us (or me at least), and I feel that all of us are aware that the honeymoon is over and we are about to lay our little pink bodies on the line. Our first shock comes as we stop our spinning motion and swing ourselves around so as to bring the Moon into view. We have not been able to see the Moon for nearly a day now, and the change is electrifying. The Moon I have known all my life, that two-dimensional small yellow disk in the sky, has gone away somewhere, to be replaced by the most awesome sphere I have ever seen. To begin with it is huge, completely filling our window. Second, it is three-dimensional. The belly of it bulges out toward us in such a pronounced fashion that I almost feel I can reach out and touch it. To add to the dramatic effect, we can see the stars again. We are in the shadow of the Moon now, and the elusive stars have reappeared.

As we ease around on the left side of the Moon, I marvel again at the precision of our path. We have missed hitting the Moon by a paltry 300 nautical miles, at a distance of nearly a quarter of a million miles from Earth, and don’t forget that the Moon is a moving target and that we are racing through the sky just ahead of its leading edge. When we launched the other day the Moon was nowhere near where it is now; it was some 40 degrees of are, or nearly 200,000 miles, behind where it is now, and yet those big computers in the basement in Houston didn’t even whimper but belched out super-accurate predictions.

As we pass behind the Moon, we have just over eight minutes to go before the burn. We are super-careful now, checking and rechecking each step several times. When the moment finally arrives, the big engine instantly springs into action and reassuringly plasters us back in our seats. The acceleration is only a fraction of one G but it feels good nonetheless. For six minutes we sit there peering intent as hawks at our instrument panel, scanning the important dials and gauges, making sure that the proper thing is being done to us. When the engine shuts down, we discuss the matter with our computer and I read out the results: “Minus one, plus one, plus one.” The accuracy of the overall system is phenomenal: out of a total of nearly three thousand feet per second, we have velocity errors in our body axis coordinate system of only a tenth of one foot per second in each of the three directions. That is one accurate burn, and even Neil acknowledges the fact.

ALDRIN: The second burn to place us in closer circular orbit of the Moon, the orbit from which Neil and I would separate from the Columbia and continue on to the Moon, was critically important. It had to be made in exactly the right place and for exactly the correct length of time. If we overburned for as little as two seconds we’d be on an impact course for the other side of the Moon. Through a complicated and detailed system of checks and balances, both in Houston and in lunar orbit, plus star checks and detailed platform alignments, two hours after our first lunar orbit we made our second burn, in an atmosphere of nervous and intense concentration. It, too, worked perfectly.

ASLEEP IN LUNAR ORBIT

We began preparing the LM. It was scheduled to take three hours, but because I had already started the checkout, we were completed a half hour ahead of schedule. Reluctantly we returned to the Columbia as planned. Our fourth night we were to sleep in lunar orbit. Although it was not in the flight plan, before covering the windows and dousing the lights, Neil and I carefully prepared all the equipment and clothing we would need in the morning, and mentally ran through the many procedures we would follow.

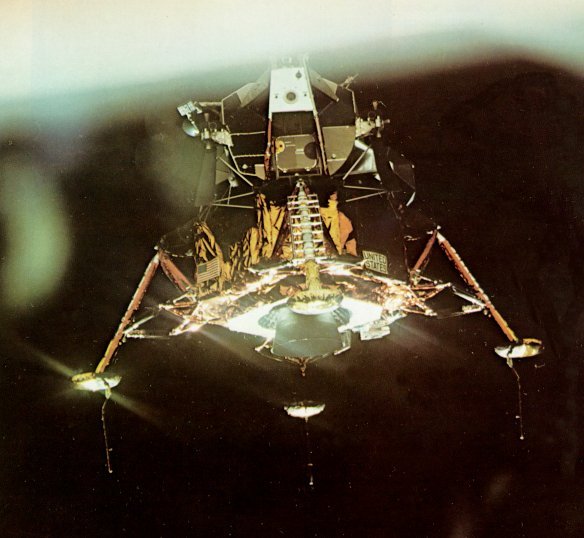

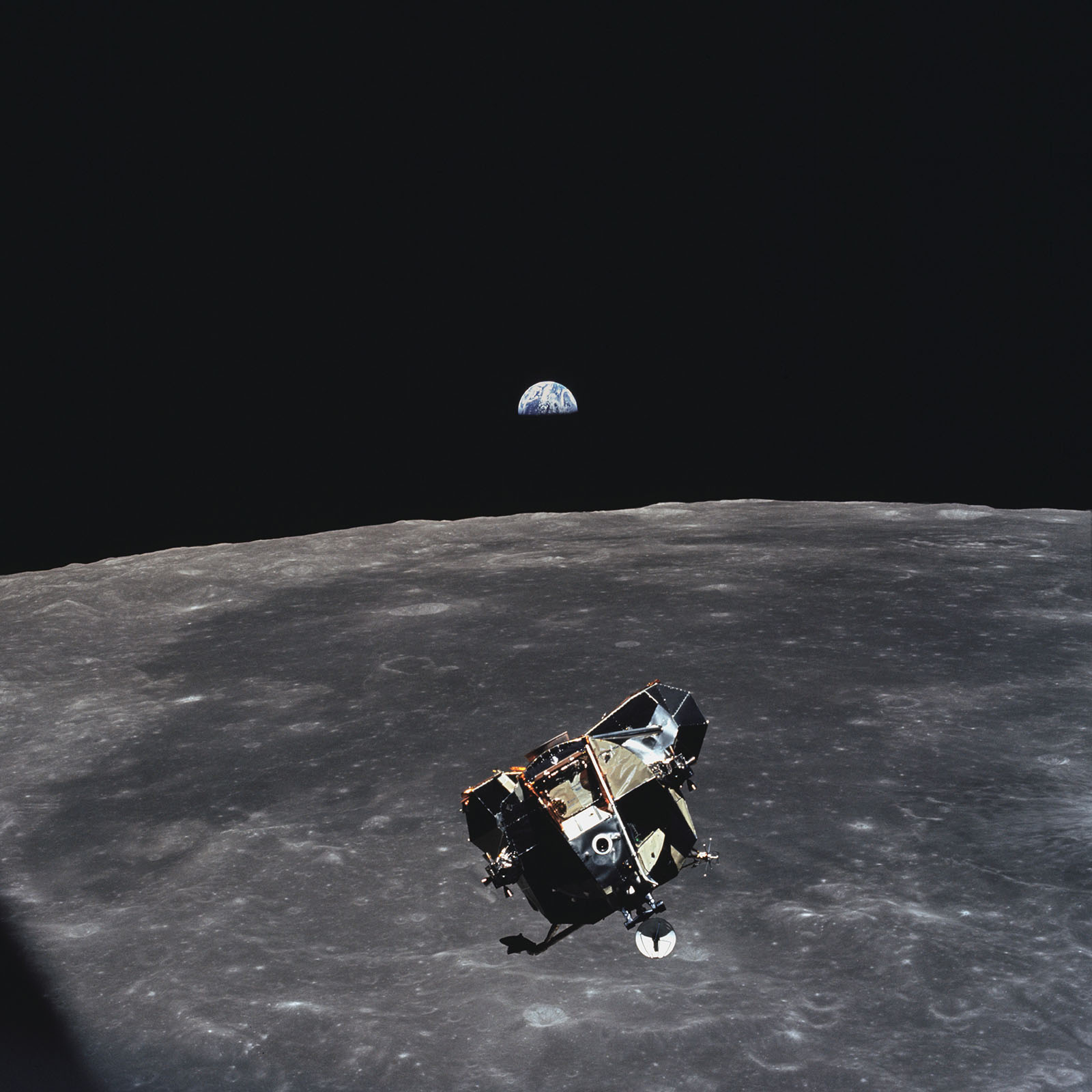

COLLINS: “Apollo 11, Apollo 11, good morning from the Black Team.” Could they be talking to me? It takes me twenty seconds to fumble for the microphone button and answer groggily, I guess I have only been asleep five hours or so; I had a tough time getting to sleep, and now I’m having trouble waking up. Neil, Buzz, and I all putter about fixing breakfast and getting various items ready for transfer into the LM. [Later] I stuff Neil and Buzz into the LM along with an armload of equipment. Now I have to do the tunnel bit again, closing hatches, installing drogue and probe, and disconnecting the electrical umbilical. I am on the radio constantly now, running through an elaborate series of joint checks with Eagle. I check progress with Buzz: “I have five minutes and fifteen seconds since we started. Attitude is holding very well.” “Roger, Mike, just hold it a little bit longer.” “No sweat, I can hold it all day. Take your sweet time. How’s the czar over there? He’s so quiet.” Neil chimes in, “Just hanging on- and punching.” Punching those computer buttons, I guess he means. “All I can say is, beware the revolution,” and then, getting no answer, I formally bid them goodbye. “You cats take it easy on the lunar surface....” “O.K., Mike,” Buzz answers cheerily, and I throw the switch which releases them. With my nose against the window and the movie camera churning away, I watch them go. When they are safely clear of me, I inform Neil, and he begins a slow pirouette in place, allowing me a look at his outlandish machine and its four extended legs. “The Eagle has wings’” Neil exults.

It doesn’t look like any eagle I have ever seen. It is the weirdest-looking contraption ever to invade the sky, floating there with its legs awkwardly jutting out above a body which has neither symmetry nor grace. I make sure all four landing gears arc down and locked, report that fact, and then lie a little, “I think you’ve got a fine-looking flying machine there. Eagle, despite the fact you’re upside down.” “Somebody’s upside down,” Neil retorts. “O.K., Eagle. One minute . . . you guys take care.” Neil answers, “See you later.” I hope so. When the one minute is up, I fire my thrusters precisely as planned and we begin to separate, checking distances and velocities as we go. This burn is a very small one, just to give Eagle some breathing room. From now on it’s up to them, and they will make two separate burns in reaching the lunar surface. The first one will serve to drop Eagle’s perilune to fifty thousand feet. Then, when they reach this spot over the eastern edge of the Sea of Tranquility, Eagle’s descent engine will be fired up for the second and last time, and Eagle will lazily are over into a 12-minute computer- controlled descent to some point at which Neil will take over for a manual landing.

ALDRIN: We were still 60 miles above the surface when we began our first burn. Neil and I were harnessed into the LM in a standing position. [Later] at precisely the right moment the engine ignited to begin the 12-minute powered descent. Strapped in by the system of belts and cables not unlike shock absorbers, neither of us felt the initial motion. We looked quickly at the computer to make sure we were actually functioning as planned. After 26 seconds the engine went to full throttle and the motion became noticeable. Neil watched his instruments while I looked at our primary computer and compared it with our second computer, which was part of our abort guidance system.

I then began a computer read-out sequence to Neil which was also being transmitted to Houston. I had helped develop it. It sounded as though I was chattering like a magpie. It also sounded as though I was doing all the work. During training we had discussed the possibility of making the communication only between Neil and myself, but Mission Control liked the idea of hearing our communications with each other. Neil had referred to it once as “that damned open mike of yours,” and I tried to make as little an issue of it as possible.

A YELLOW CAUTION LIGHT

At six thousand feet above the lunar surface a yellow caution light came on and we encountered one of the few potentially serious problems in the entire flight, a problem which might have caused us to abort, had it not been for a man on the ground who really knew his job.

COLLINS: At five minutes into the burn, when I am nearly directly overhead, Eagle voices its first concern. “Program Alarm,” barks Neil, “It’s a 1202.” What the hell is that? I don’t have the alarm numbers memorized for my own computer, much less for the LM’s. I jerk out my own checklist and start thumbing through it, but before I can find 1202, Houston says, “Roger, we’re GO on that alarm.” No problem, in other words. My checklist says 1202 is an “executive overflow,” meaning simply that the computer has been called upon to do too many things at once and is forced to postpone some of them. A little farther along, at just three thousand feet above the surface, the computer flashes 1201, another overflow condition, and again the ground is superquick to respond with reassurances.

ALDRIN: Back in Houston, not to mention on board the Eagle, hearts shot up into throats while we waited to learn what would happen. We had received two of the caution lights when Steve Bales the flight controller responsible for LM computer activity, told us to proceed, through Charlie Duke, the capsule communicator. We received three or four more warnings but kept on going. When Mike, Neil, and I were presented with Medals of Freedom by President Nixon, Steve also received one. He certainly deserved it, because without him we might not have landed.

ARMSTRONG: In the final phases of the descent after a number of program alarms, we looked at the landing area and found a very large crater. This is the area we decided we would not go into; we extended the range downrange. The exhaust dust was kicked up by the engine and this caused some concern in that it degraded our ability to determine not only our altitude in the final phases but also our translational velocities over the ground. It’s quite important not to stub your toe during the final phases of touchdown.

From the space-to-ground tapes:

EAGLE: 540 feet, down at 30 [feet per second] . . . down at 15 . . . 400 feet down at 9 . . . forward . . . 350 feet, down at 4 . . . 300 feet, down 3½ . . . 47 forward . . . 1½ down . . . 13 forward . . . 11 forward? coming down nicely . . . 200 feet, 4½ down . . . 5½ down . . . 5 percent . . . 75 feet . . . 6 forward . . . lights on . . . down 2½ . . . 40 feet? down 2½, kicking up some dust . . . 30 feet, 2½ down . . . faint shadow . . . 4 forward . . . 4 forward . . . drifting to right a little . . . O.K. . . .

HOUSTON: 30 seconds [fuel remaining].

EAGLE: Contact light! O.K., engine stop . . . descent engine command override off . . .

HOUSTON: We copy you down, Eagle.

EAGLE: Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed!

HOUSTON: Roger, Tranquility. We copy you on the ground. You’ve got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.

TRANQUILITY: Thank you . . . That may have seemed like a very long final phase. The auto targeting was taking us right into a football-field-sized crater, with a large number of big boulders and rocks for about one or two crater-diameters around it, and it required flying manually over the rock field to find a reasonably good area.

HOUSTON: Roger, we copy. It was beautiful from here, Tranquility. Over.

TRANQUILITY: We’ll get to the details of what’s around here, but it looks like a collection of just about every variety of shape, angularity, granularity, about every variety of rock you could find.

HOUSTON: Roger, Tranquility. Be advised there’s lots of smiling faces in this room, and all over the world.

TRANQUILITY: There are two of them up here.

COLUMBIA: And don’t forget one in the command module.

ARMSTRONG: Once [we] settled on the surface, the dust settled immediately and we had an excellent view of the area surrounding the LM. We saw a crater surface, pockmarked with craters up to 15, 20, 30 feet, and many smaller craters down to a diameter of 1 foot and, of course, the surface was very fine- grained. There were a surprising number of rocks of all sizes.

A number of experts had, prior to the flight, predicted that a good bit of difficulty might be encountered by people due to the variety of strange atmospheric and gravitational characteristics. This didn’t prove to be the case and after landing we felt very comfortable in the lunar gravity. It was, in fact, in our view preferable both to weightlessness and to the Earth’s gravity.

When we actually descended the ladder it was found to be very much like the lunar-gravity simulations we had performed here on Earth. No difficulty was encountered in descending the ladder. The last step was about 3½ feet from the surface, and we were somewhat concerned that we might have difficulty in reentering the LM at the end of our activity period. So we practiced that before bringing the camera down.

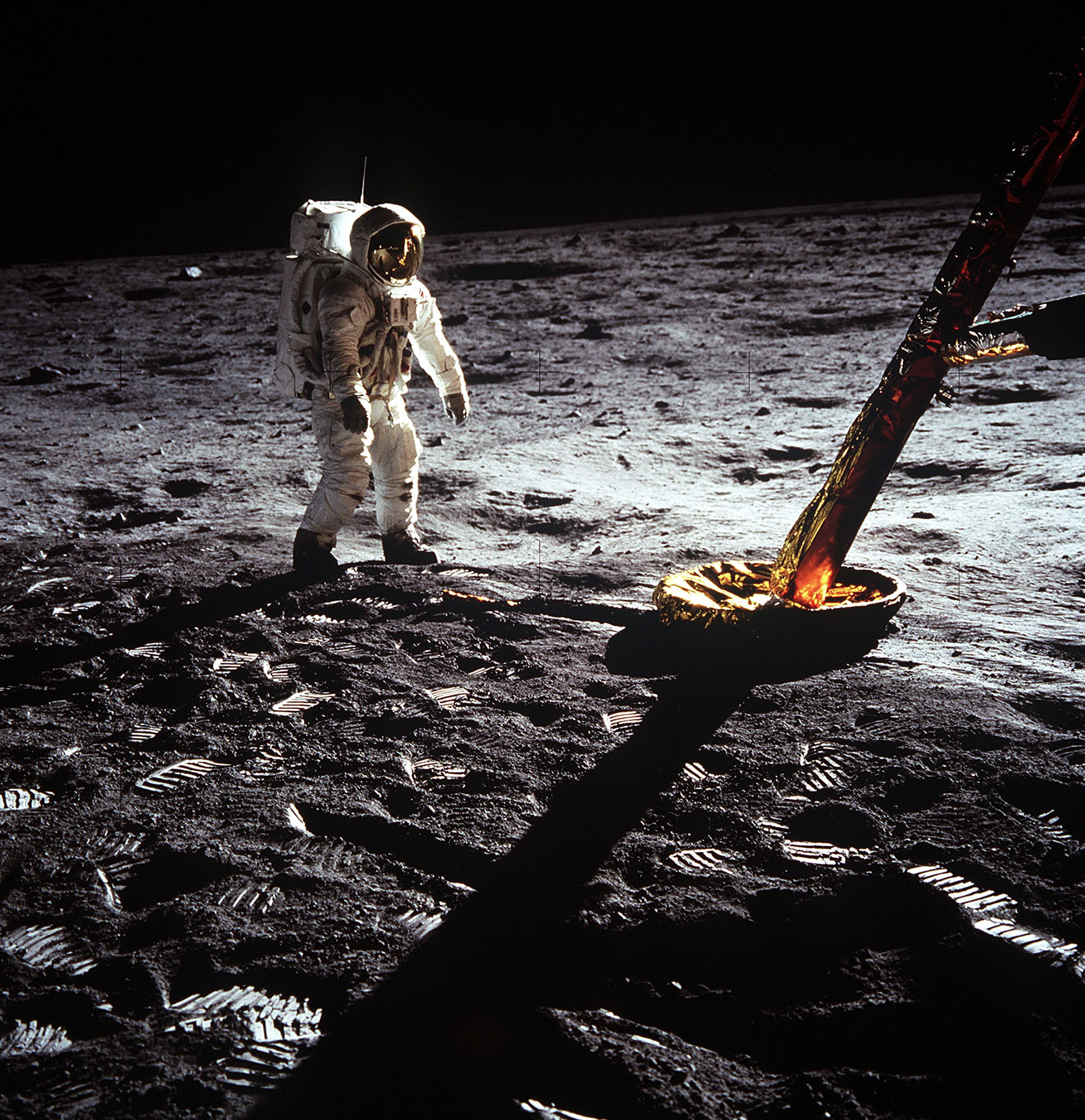

ALDRIN: We opened the hatch and Neil, with me as his navigator, began backing out of the tiny opening. It seemed like a small eternity before I heard Neil say, “That’s one small step for man . . . one giant leap for mankind.” In less than fifteen minutes I was backing awkwardly out of the hatch and onto the surface to join Neil, who, in the tradition of all tourists, had his camera ready to photograph my arrival.

I felt buoyant and full of goose pimples when I stepped down on the surface. I immediately looked down at my feet and became intrigued with the peculiar properties of the lunar dust. If one kicks sand on a beach, it scatters in numerous directions with some grains traveling farther than others. On the Moon the dust travels exactly and precisely as it goes in various directions, and every grain of it lands nearly the same distance away.

THE BOY IN THE CANDY STORE

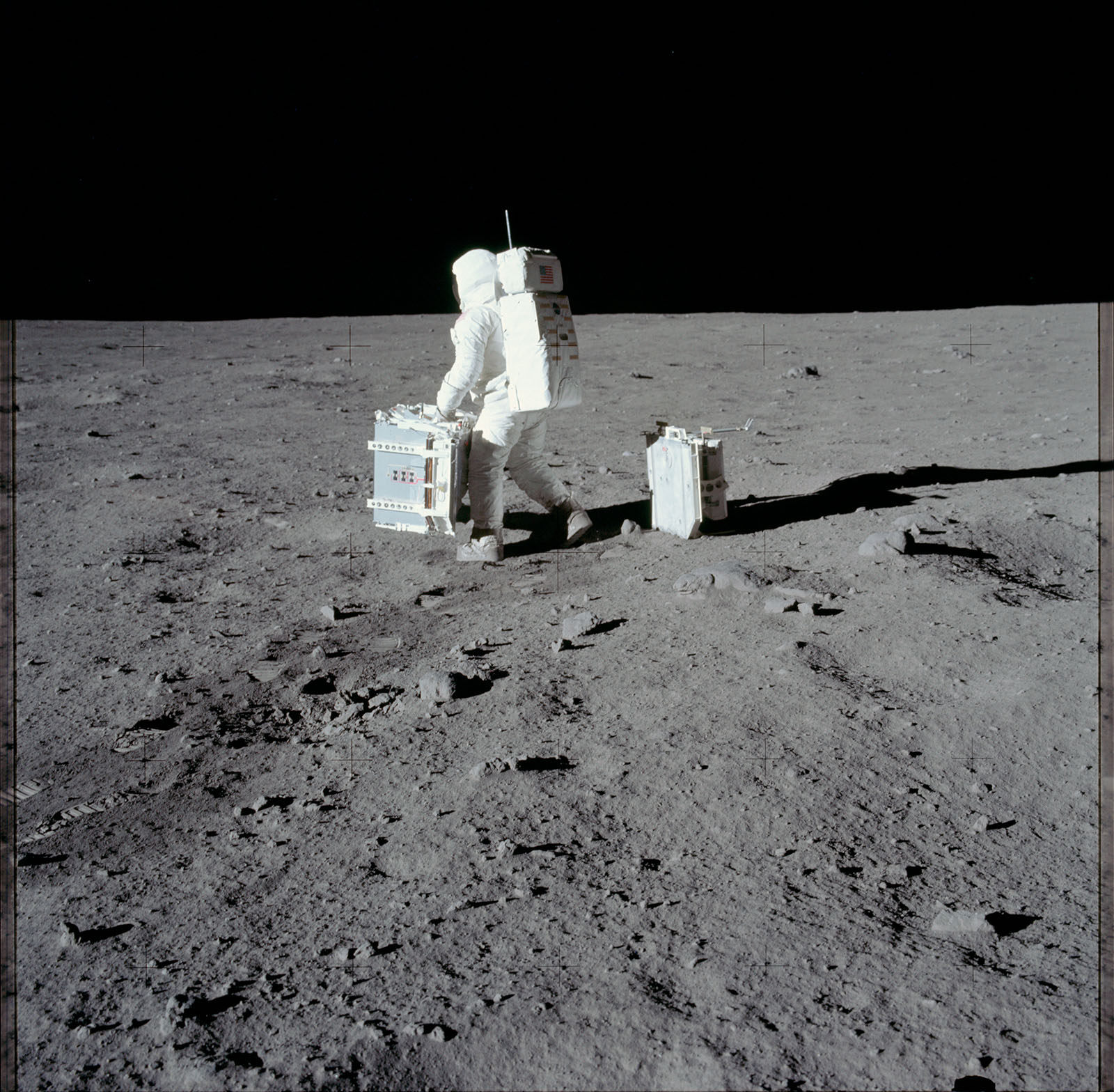

ARMSTRONG: There were a lot of things to do, and we had a hard time getting, them finished. We had very little trouble, much less trouble than expected, on the surface. It was a pleasant operation. Temperatures weren’t high. They were very comfortable. The little EMU, the combination of spacesuit and backpack that sustained our life on the surface, operated magnificently. The primary difficulty was just far too little time to do the variety of things we would have liked. We had the problem of the five-year-old boy in a candy store.

ALDRIN: I took off jogging to test my maneuverability. The exercise gave me an odd sensation and looked even more odd when I later saw the films of it. With bulky suits on, we seemed to be moving in slow motion. I noticed immediately that my inertia seemed much greater. Earth-bound, I would have stopped my run in just one step, but I had to use three of four steps to sort of wind down. My Earth weight, with the big backpack and heavy suit, was 360 pounds. On the Moon I weighed only 60 pounds.

At one point I remarked that the surface was “Beautiful, beautiful. Magnificent desolation.” I was struck by the contrast between the starkness of the shadows and the desert-like barrenness of the rest of the surface. It ranged from dusty gray to light tan and was unchanging except for one startling sight: our LM sitting there with its black, silver, and bright yellow- orange thermal coating shining brightly in the otherwise colorless landscape. I had seen Neil in his suit thousands of times before, but on the Moon the unnatural whiteness of it seemed unusually brilliant. We could also look around and see the Earth, which, though much larger than the Moon the Earth was seeing, seemed small - a beckoning oasis shining far away in the sky.

As the sequence of lunar operations evolved, Neil had the camera most of the time, and the majority of pictures taken on the Moon that include an astronaut are of me. It wasn’t until we were back on Earth and in the Lunar Receiving Laboratory looking over the pictures that we realized there were few pictures of Neil. My fault perhaps, but we had never simulated this in our training.

COAXING THE FLAG TO STAND

During a pause in experiments, Neil suggested we proceed with the flag. It took both of us to set it up and it was nearly a disaster. Public Relations obviously needs practice just as everything else does. A small telescoping arm was attached to the flagpole to keep the flag extended and perpendicular. As hard as we tried, the telescope wouldn’t fully extend. Thus the flags which should have been flat, had its own unique permanent wave. Then to our dismay the staff of the pole wouldn’t go far enough into the lunar surface to support itself in an upright position. After much struggling we finally coaxed it to remain upright, but in a most precarious position. I dreaded the possibility of the American flag collapsing into the lunar dust in front of the television camera.

COLLINS: [On his fourth orbital pass above] “How’s it going?” “The EVA is progressing beautifully. I believe they’re setting up the flag now.” Just let things keep going that way, and no surprises, please. Neil and Buzz sound good, with no huffing and puffing to indicate they are overexerting themselves. But one surprise at least is in store. Houston comes on the air, not the slightest bit ruffled, and announces that the President of the United States would like to talk to Neil and Buzz. “That would be an honor,” says Neil, with characteristic dignity.

The President’s voice smoothly fills the air waves with the unaccustomed cadence of the speechmaker, trained to convey inspiration, or at least emotion, instead of our usual diet of numbers and reminders. “Neil and Buzz, I am talking to you by telephone from the Oval Office at the White House, and this certainly has to be the most historic telephone call ever made . . . Because of what you have done, the heavens have become a part of man’s world. As you talk to us from the Sea of Tranquility, it inspires us to redouble our efforts to bring peace and tranquility to Earth . . .” My God, I never thought of all this bringing peace and tranquility to anyone. As far as I am concerned, this voyage is fraught with hazards for the three of us- and especially two of us- and that is about as far as I have gotten in my thinking.

Neil, however, pauses long enough to give as well as he receives. “It’s a great honor and privilege for us to be here, representing not only the United States but men of peace of all nations, and with interest and a curiosity and a vision for the future.”

[Later] Houston cuts off the White House and returns to business as usual, with a long string of numbers for me to copy for future use. My God, the juxtaposition of the incongruous: roll, pitch, and yaw; prayers, peace, and tranquility. What will it be like if we really carry this off and return to Earth in one piece, with our boxes full of rocks and our heads full of new perspectives for the planet? I have a little time to ponder this as I zing off out of sight of the White House and the Earth.

ALDRIN: We had a pulley system to load on the boxes of rocks. We found the process more time-consuming and dust-scattering than anticipated. After the gear and both of us were inside, our first chore was to pressure the LM cabin and begin stowing the rock boxes, film magazines, and anything else we wouldn’t need until we were connected once again with the Columbia. We removed our boots and the big backpacks, opened the LM hatch, and threw these items onto the lunar surface, along with a bagful of empty food packages and the LM urine bags. The exact moment we tossed every thing out was measured back on Earth- the seismometer we had put out was even more sensitive than we had expected.

Before beginning liftoff procedures [we] settled down for our fitful rest. We didn’t sleep much at all. Among other things we were elated- and also cold. Liftoff from the Moon, after a stay totaling twenty-one hours, was exactly on schedule and fairly uneventful. The ascent stage of the LM separated, sending out a shower of brilliant insulation particles which had been ripped off from the thrust of the ascent engine. There was no lime to sightsee. I was concentrating on the computers, and Neil was studying the attitude indicator, but I looked up long enough to see the flag fall over . . . Three hours and ten minutes later we were connected once again with the Columbia.

COLLINS: I can look out through my docking reticle and see that they are steady as a rock as they drive down the center line of that final approach path. I give them some numbers. “I have 0.7 mile and I got you at 31 feet per second.” We really are going to carry this off? For the first time since I was assigned to this incredible flight, I feel that it is going to happen. Granted, we are a long way from home, but from here on it should be all downhill. Within a few seconds Houston joins the conversation, with a tentative little call. “Eagle and Columbia, Houston standing by.” They want to know what the hell is going on, but they don’t want to interrupt us if we are in a crucial spot in our final maneuvering. Good heads! However, they needn’t worry, and Neil lets them know it. “Roger, we’re stationkeeping.”

ALL SMILES AND GIGGLES

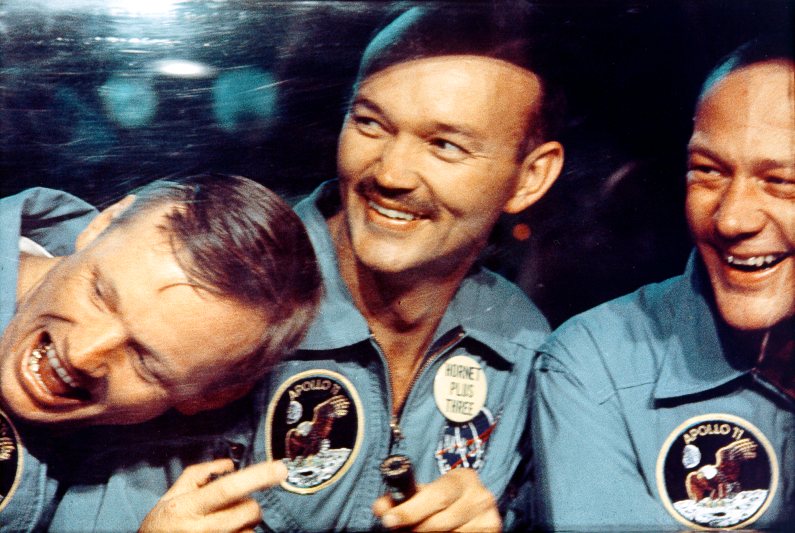

[After docking] it’s time to hustle down into the tunnel and remove hatch, probe, and drogue, so Neil and Buzz can get through. Thank God, all the claptrap works beautifully in this its final workout. The probe and drogue will stay with the LM and be abandoned with it, for we will have no further need of them and don’t want them cluttering up the command module. The first one through is Buzz, with a big smile on his face. I grab his head, a hand on each temple, and am about to give him a smooch on the forehead, as a parent might greet an errant child; but then, embarrassed, I think better of it and grab his hand, and then Neil’s. We cavort about a little bit, all smiles and giggles over our success, and then it’s back to work as usual.

Excerpts from a TV program broadcast by the Apollo 11 astronauts on the last evening of the flight, the day before splashdown in the Pacific:

COLLINS: “. . . The Saturn V rocket which put us in orbit is an incredibly complicated piece of machinery, every piece of which worked flawlessly. This computer above my head has a 38,000-word vocabulary, each word of which has been carefully chosen to be of the utmost value to us. The SPS engine, our large rocket engine on the aft end of our service module, must have performed flawlessly or we would have been stranded in lunar orbit. The parachutes up above my head must work perfectly tomorrow or we will plummet into the ocean. We have always had confidence that this equipment will work properly. All this is possible only through the blood, sweat, and tears of a number of people. First, the American workmen who put these pieces of machinery together in the factory. Second, the painstaking work done by various test teams during the assembly and retest after assembly. And finally, the people at the Manned Spacecraft Center, both in management, in mission planning, in flight control, and last but not least, in crew training. This operation is somewhat like the periscope of a submarine. All you see is the three of us, but beneath the surface are thousands and thousands of others, and to all of those, I would like to say, ‘thank you very much.’”

ALDRIN: “. . . This has been far more than three men on a mission to the Moon; more, still, than the efforts of a government and industry team; more, even, than the efforts of one nation. We feel that this stands as a symbol of the insatiable curiosity of all mankind to explore the unknown. Today I feel we’re really fully capable of accepting expanded roles in the exploration of space. In retrospect, we have all been particularly pleased with the call signs that we very laboriously chose for our spacecraft, Columbia and Eagle. We’ve been pleased with the emblem of our flight, the eagle carrying an olive branch, bringing the universal symbol of peace from the planet Earth to the Moon. Personally, in reflecting on the events of the past several days, a verse from Psalms comes to mind. ‘When I consider the heavens, the work of Thy fingers, the Moon and the stars, which Thou hast ordained; What is man that Thou art mindful of him?’”

ARMSTRONG: “The responsibility for this flight lies first with history and with the giants of science who have preceded this effort; next with the American people, who have, through their will, indicated their desire; next with four administrations and their Congresses, for implementing that will; and then, with the agency and industry teams that built our spacecraft, the Saturn, the Columbia, the Eagle, and the little EMU, the spacesuit and backpack that was our small spacecraft out on the lunar surface. We would like to give special thanks to all those Americans who built the spacecraft; who did the construction, design, the tests, and put their hearts and all their abilities into those craft. To those people tonight, we give a special thank you, and to all the other people that are listening and watching tonight, God bless you. Good night from Apollo 11.”

[Portions of the text of this chapter have been excerpted with permission from

Carrying the Fire, © 1974 by Michael Collins, and

Return to Earth, © 1973 by Aldrin-Warga Associates.]