The Shakedown Cruises

By SAMUEL C. PHILLIPS

Consider the mood of America as it approached the end of 1968, by any accounting one of the unhappiest years of the twentieth century. It was a year of riots, burning cities, sickening assassinations, universities forced to close their doors. In Southeast Asia the twelve-month toll of American dead rose 50 percent, to 15,000, and the cost of the war topped $25 billion. By mid-December the country’s despair was reflected in the Associated Press’s nationwide poll of editors, who chose as the two top stories of 1968 the slayings of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King; Time magazine picked a generic symbol, “The Dissenter”, as its Man of the Year. The poll and the Man were scheduled for year-end publication.

This condition was changed dramatically during the waning days of the year, figuratively with two out in the last half of the ninth, and that is what this chapter is about.

Nineteen sixty-seven, which began as a bad year for the space program, had had its own sensational upturn with the first flight, unmanned, of the giant Saturn, on November 9 - a landmark on the path to the Moon. Then 1968 started fairly well with Apollo 5, the first flight of the lunar module on January 22, which proved the structural integrity and operating characteristics of the Moon lander, despite overly conservative computer programming that caused the descent propulsion system to shut off too soon.

The second unmanned Saturn V mission, numbered Apollo 6, on April 4, 1968, was less successful. For a time it raised fears that the Moon-landing schedule had suffered another major setback. Three serious flaws turned up. Two minutes and five seconds after launch the 363-foot Saturn V underwent a lengthwise oscillation, like the motion of a pogo stick. Pogo oscillation subjects the entire space-vehicle stack to stresses and strains that, under certain circumstances, can grow to a magnitude sufficient to damage or even destroy the vehicle. This motion, caused by a synchronization of engine thrust pulsations with natural vibration frequencies of the vehicle structure, tends to be self-amplifying as the structural oscillations disturb the flow of propellants and thus magnify the thrust pulsations.

The second anomaly, loss of structural panels from the lunar module adapter (the structural section that would house the lunar module), was originally thought to have been caused by the pogo oscillations. Engineers at Houston were able to establish, however, that a faulty manufacturing process was to blame. This was quickly corrected.

The third problem encountered on this flight was more serious. After the first stage had finished its work, the second stage was to take over and put Apollo 6 into orbit; then the third stage, the S-IVB, would take the CSM up to 13,800 miles, from where reentry from the Moon would be simulated, retesting the command module heat shield at the 25,000 mph that Apollo 4 had achieved five months earlier.

The second stage’s five J-2 engines ignited as scheduled. About two-thirds of the way through their scheduled burn, no. 2 engine lost thrust and a detection system shut it down. No. 3 engine followed suit. With two-fifths of the second stage’s million-pound thrust gone, Apollo 6, with the help of the single J-2 engine of the third stage, still achieved orbit, though in an egg-shaped path. But when the attempt was made to fire the third stage’s engine a second time - as would be necessary to send astronauts into translunar trajectory - the single J-2 failed to ignite. The mission was saved when the service module’s propulsion-system engine - 20,000 pounds of thrust as against the third stage’s 225,000 - took over and sent the CSM up to the desired 13,800-mile altitude from which it reentered the atmosphere and landed in the Pacific.

DETECTIVE WORK ON THE TELEMETRY

What had happened? Ferreting out clues from mission records and the reams of data recorded from telemetry was a fascinating story of technical detective work. More than a thousand engineers and technicians at NASA Centers, contractor plants, and several universities were involved in establishing causes and designing and testing fixes.

The solution for pogo was to modify the pre-valves of the second-stage engines so that they could be charged with helium gas. This provided shock-absorbing accumulators that damped out the thrust oscillations.

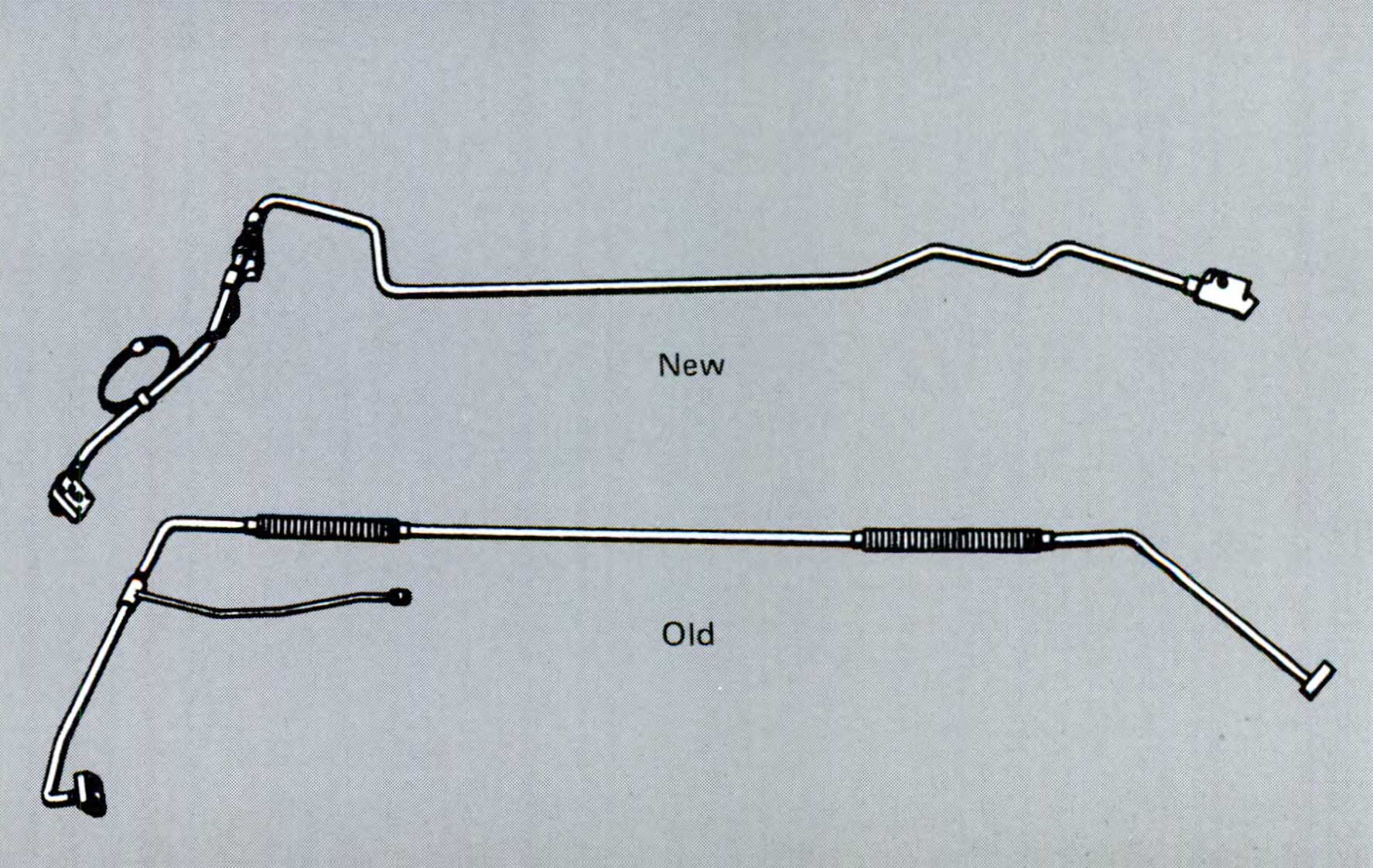

Finding the culprit that cut off the J-2 engines involved long theorizing and hundreds of tests that finally pinpointed a six-foot tube, half an inch in diameter, carrying liquid hydrogen to the starter cup of the engine. This line had been fitted with two small bellows for absorbing vibration. It worked fine on ground tests because ice forming on the bellows provided a damping effect. But in the dryness of space - eventually simulated in a vacuum chamber - no ice formed because there was no air from which to draw moisture, and there the lines vibrated, cracked, and broke. The fix: replace the bellows with bends in the tubes to take up the motion.

With careful engineering analysis and extensive testing we satisfied ourselves that we understood the problems that plagued Apollo 6 and that the resulting changes were more than adequate to commit the third Saturn V to manned flight.

At this point we planned that the next Saturn V would be the D mission, launching Apollo 8 in December with Astronauts McDivitt, Scott, and Schweickart. Their main objective would be to test the spider-like lunar module then abuilding at the Grumman plant on Long Island. Early in 1968 we had set the objective of flying the D mission before the year was out. It was a reasonable target at the time, considering progress across the program, and would put us in an excellent position to complete the preparatory missions and have more than one shot at the landing in 1969.

Meanwhile, the command and service modules, after almost two years of reworking at the North American Aviation plant in Downey, Calif., would have their crucial flight test on Apollo 7, the C mission, after launch in October 1968 by the smaller Saturn IB. On board this first manned Apollo mission would be Astronauts Schirra, Eisele, and Cunningham.

By midsummer it was apparent that Apollo 7 would fly in October, but that the lunar module for the D mission would not be ready for a December flight. Electromagnetic interference problems were plaguing checkout tests, and it was obvious that engineering changes and further time-consuming tests were needed. After a comprehensive review in early August, my unhappy estimate was that the D mission would not be ready until March 1969.

AN EARLY TRIP AROUND THE MOON

George Low, the spacecraft program manager, then put forward a daring idea: fly the CSM on the Saturn V in December, with a dummy instead of the real LM, all the way to the Moon. We would then make maximum progress for the program, while we took the time necessary to work out rigorously the LM problems. Low had discussed the feasibility of such a mission with Gilruth, Kraft, and Slayton at the Manned Spacecraft Center; I was at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida when he called to voice his idea. The upshot was a meeting that afternoon of the Apollo management team. The Marshall Space Flight Center at Huntsville, Ala., was a central point, considering where we all were at the moment. George Hage, my deputy, and I joined with Debus and Petrone of KSC for the flight to Huntsville. Von Braun, Rees, James, and Richard of MSFC were there. Gilruth, Low, Kraft, and Slayton flew from Houston.

We discussed designing a flexible mission so that, depending on many factors, including results of the Apollo 7 flight, we could commit Apollo 8 to an Earth-orbit flight, or a flight to a few hundred or several thousand miles away from Earth, or to a lunar flyby, or to spending several hours in lunar orbit. The three-hour conference didn’t turn up any “show-stoppers”. Quite the opposite; while there were many details to be reexamined, it indeed looked as if we could do it. The gloom that had permeated our previous program review was replaced by excitement. We agreed to meet in Washington five days later. If more complete investigation uncovered no massive roadblocks, I would fly to Vienna for an exegesis to my boss, Dr. George E. Mueller, Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight, and to the NASA Administrator, James Webb, who were attending a United Nations meeting on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. (Going to Vienna was at first considered necessary, lest other communications tip off the Russians, believed to be planning a Moon spectacular of their own. Eventually it was decided that my appearance in Vienna would trip more alarms than overseas telephone conversations.)

Many problems remained. The high-gain antenna was an uncertain quantity; but Kraft agreed that the mission could be flown safely with the omniantennas, even though television might be lost. What should we carry in lieu of the LM? The answer was the LM test article that had been through the dynamics program at Marshall. Deke Slayton wanted to leave McDivitt and his crew assigned to the first LM mission; so the next crew, Borman, Lovell, and Anders, scheduled for the E mission, were brought forward for the newly defined Apollo 8 mission. McDivitt’s mission retained its D designation, and Borman’s was labeled “C-Prime”.

Upon returning to Washington, I presented the plan to Thomas O. Paine, Acting Administrator in Webb’s absence. Paine reminded me that the program had fallen behind, pogo had occurred on the last flight, three engines had failed, and we had not yet flown a manned Apollo mission; yet “now you want to up the ante. Do you really want to do this, Sam?” My answer was, “Yes, sir, as a flexible mission, provided our detailed examination in days to come doesn’t turn up any show-stoppers.” Said Paine, “We’ll have a hell of a time selling it to Mueller and Webb.”

He was right. A telephone conversation with Mueller in Vienna found him skeptical and cool. Mr. Webb was clearly shaken by the abrupt proposal and by the consequences of possible failure.

On August 15 Paine and I sent Webb and Mueller a seven-page cable with suggested wording of a press release saying lunar orbit was being retained as an option in the December flight, the decision to depend on the success of Apollo 7 in October. Webb replied from Vienna via State Department code, accepting the crew switches and schedule changes. But he proposed saying only that “studies will be carried out and plans prepared so as to provide reasonable flexibility in establishing final mission objectives” after Apollo 7.

Paine interpreted Webb’s instructions “liberally”, and authorized me to say in an August 19 press conference, upon announcing the McDivitt-Borman switch, that a circumlunar flight or lunar orbit were possible options. I am told that I diminished the possibility so thoroughly, by saying repeatedly “the basic mission is Earth orbit”, that the press at first mostly missed the point.

October 11 at Cape Kennedy was hot but the heat was tempered by a pleasant breeze when Apollo 7 lifted off in a two-tongued blaze of orange-colored flame at 11:02:45. The Saturn IB, in its first trial with men aboard, provided a perfect launch and its first stage dropped off 2 minutes 25 seconds later. The S-IVB second stage took over, giving astronauts their first ride atop a load of liquid hydrogen, and at 5 minutes 54 seconds into the mission, Walter Schirra, the commander, reported, “She is riding like a dream”. About five minutes later an elliptical orbit had been achieved, 140 by 183 miles above the Earth. The S-IVB stayed with the CSM for about one and one-half orbits, then separaten. Schirra fired the CSM’s small rockets to pull 50 feet ahead of the S-IVB, then turned the spacecraft around to simulate docking, as would be necessary to extract an LM for a Moon landing. Next day, when the CSM and the S-IVB were about 80 miles apart, Schirra and his mates sought out the lifeless, tumbling 59-foot craft in a rendezvous simulation and approached within 70 feet.

A SUPERB SPACECRAFT

During the 163 orbits of Apollo 7 the ghost of Apollo 204 was effectively exorcised as the new Block II spacecraft and its millions of parts performed superbly. Durability was shown for 10.8 days - longer than a journey to the Moon and back. A momentary shudder went through Mission Control when both AC buses dropped out of the spacecraft’s electrical system, coincident with automatic cycles of the cryogenic oxygen tank fans and heaters; but manual resetting of the AC bus breakers restored normal service. Three of the five spacecraft windows fogged because of improperly cured sealant compound (a condition that could not be fixed until Apollo 9). Chargers for the batteries needed for reentry (after fuel cells departed with the SM) returned 50 to 75 percent less energy than expected. Most serious was the overheating of fuel cells, which might have failed when the spacecraft was too far from Earth to return on batteries, even if fully charged. But each of these anomalies was satisfactorily checked out before Apollo 8 flew.

The CSM’s service propulsion system, which had to fire the CSM into and out of Moon orbit, worked perfectly during eight burns lasting from half a second to 67.6 seconds. Apollo’s flotation bags had their first try-out when the spacecraft, a “lousy boat”, splashed down south of Bermuda and turned upside down; when inflated, the brightly colored bags flipped it aright.

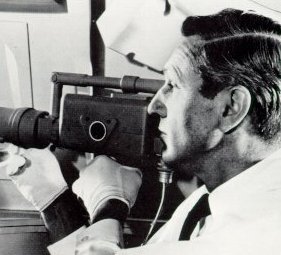

In retrospect it seems inconceivable, but serious debate ensued in NASA councils on whether television should be broadcast from Apollo missions, and the decision to carry the little 4½-pound camera was not made until just before this October flight. Although these early pictures were crude, I think it was informative for the public to see astronauts floating weightlessly in their roomy spacecraft, snatching floating objects, and eating the first hot food consumed in space. Like the television pictures, the food improved in later missions.

Apollo 7’s achievement led to a rapid review of Apollo 8’s options. The Apollo 7 astronauts went through six days of debriefing for the benefit of Apollo 8, and on October 28 the Manned Space Flight Management Council chaired by Mueller met at MSC, investigating every phase of the forthcoming mission. Next day came a lengthy systems review of Apollo 8’s Spacecraft 103. Paine made the go/no-go review of lunar orbit on November 11 at NASA Headquarters in Washington. By this time nearly all the skeptics bad become converts.

At the end of this climactic meeting Mueller put a recommendation for lunar orbit into writing, and Paine approved it. He telephoned the decision to the White House, and the message was laid on President Johnson’s desk while he was conferring with Richard M. Nixon, elected his successor six days earlier.

LIFTING FROM A SEA OF FLAME

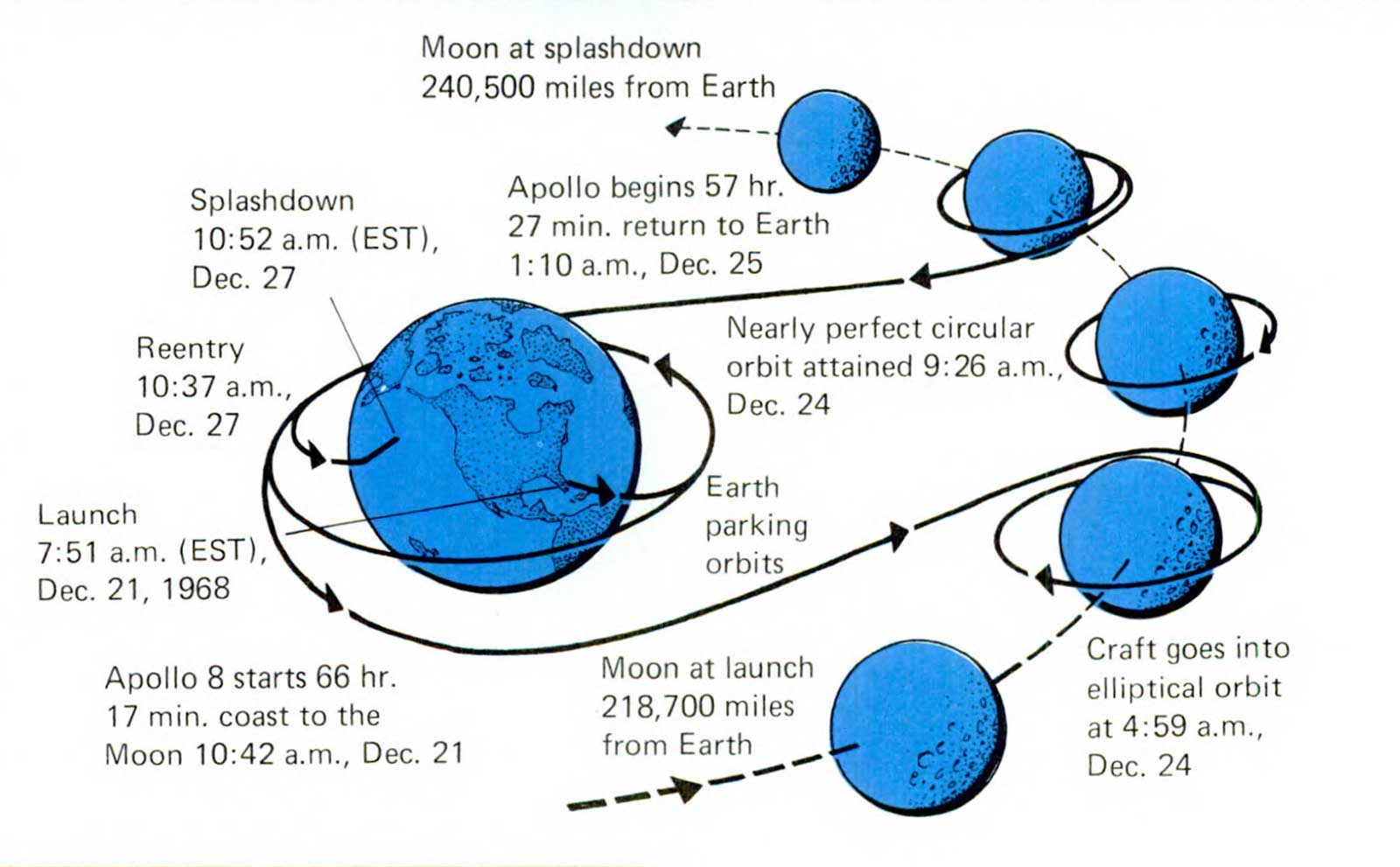

In the pink dawn of December 21 a quarter million persons lined the approaches to Cape Kennedy, many of them having camped overnight. At 7:51, amid a noise that sounded from three miles away like a million-ton truck rumbling over a corrugated road, the first manned Saturn V, an alabaster column as big as a naval destroyer, lifted slowly, ever so slowly, from the sea of flame that engulfed Pad 39-A. The upward pace quickened as the first stage’s 531,000 gallons of kerosene and liquid oxygen were thirstily consumed, and in 2 minutes 34 seconds the big drink was finished, whereupon the second stage’s five J-2 engines lit up. S-II’s 359,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen boosted the S-IVB and CSM for 6 minutes 10 seconds to an altitude of 108 miles. After the depleted S-II fell away, the S-IVB, this time the third stage, fired for 2 minutes 40 seconds to achieve Earth orbit. Except for slight pogo during the second-stage burn, Commander Borman reported all was smoothness.

During the second orbit, at 2 hours 27 minutes, CapCom Mike Collins sang out “You are go for TLI” (translunar injection), and 23 minutes after that Lovell calmly said, “Ignition”. The S-IVB had restarted with a long burn over Hawaii that lasted 5 minutes 19 seconds and boosted speed to the 24,200 mph necessary to escape the bonds of Earth. “You are on your way”, said Chris Kraft, from the last row of consoles in Mission Control, “you are really on your way”. The anticlimactic observation of the day came when Lovell said, “Tell Conrad he lost his record”. (During Gemini 11 Pete Conrad and Dick Gordon had set an altitude record of 850 miles.) After the burn the S-IVB separated and was sent on its way to orbit the Sun.

In Mission Control early in the morning of December 24 the big center screen, which had carried an illuminated Mercator projection of the Earth for the past three and one-half years - a moving blip always indicated the spacecraft’s position - underwent a dramatic change. The Earth disappeared, and upon the screen was flashed a scarred and pockmarked map with such labels as Mare Tranquillitatis, Mare Crisium, and many craters with such names as Tsiolkovsky, Grimaldi, and Gilbert. The effect was electrifying, symbolic evidence that man had reached the vicinity of the Moon.

CapCom Gerry Carr spoke to the three astronauts more than 200,000 miles away, “Ten seconds to go. You are GO all the way.” Lovell replied, “We’ll see you on the other side”, and Apollo 8 disappeared behind the Moon, the first time in history men had been occulted. For 34 minutes there would be no way of knowing what happened. During that time the 247-second LOI (lunar orbit insertion) burn would take place that would slow down the spacecraft from 5758 to 3643 mph to enable it to latch on to the Moon’s field of gravity and go into orbit. If the SPS engine failed, Apollo 8 would whip around the Moon and head back for Earth on a free-return trajectory (ála Apollo 13); during one critical half minute if the engine conked out the spacecraft would be sent crashing into the Moon.

ORBITING THE MOON CHRISTMAS EVE

”Longest four minutes I ever spent”, said Lovell during the burn, in a comment recorded but not broadcast in real time. At 69 hours 15 minutes Apollo 8 went into lunar orbit, whereupon Anders said, “Congratulations, gentlemen, you are at zero-zero”. Said Borman, “It’s not time for congratulations yet. Dig out the flight plan.”

Unaware of this conversation, Mission Control buzzed with nervous chatter. Carr began seeking a signal to indicate that the astronauts were indeed in orbit: “Apollo 8, Apollo 8, Apollo 8.” Then the voice of Jim Lovell came through calmly, “Go ahead, Houston.”

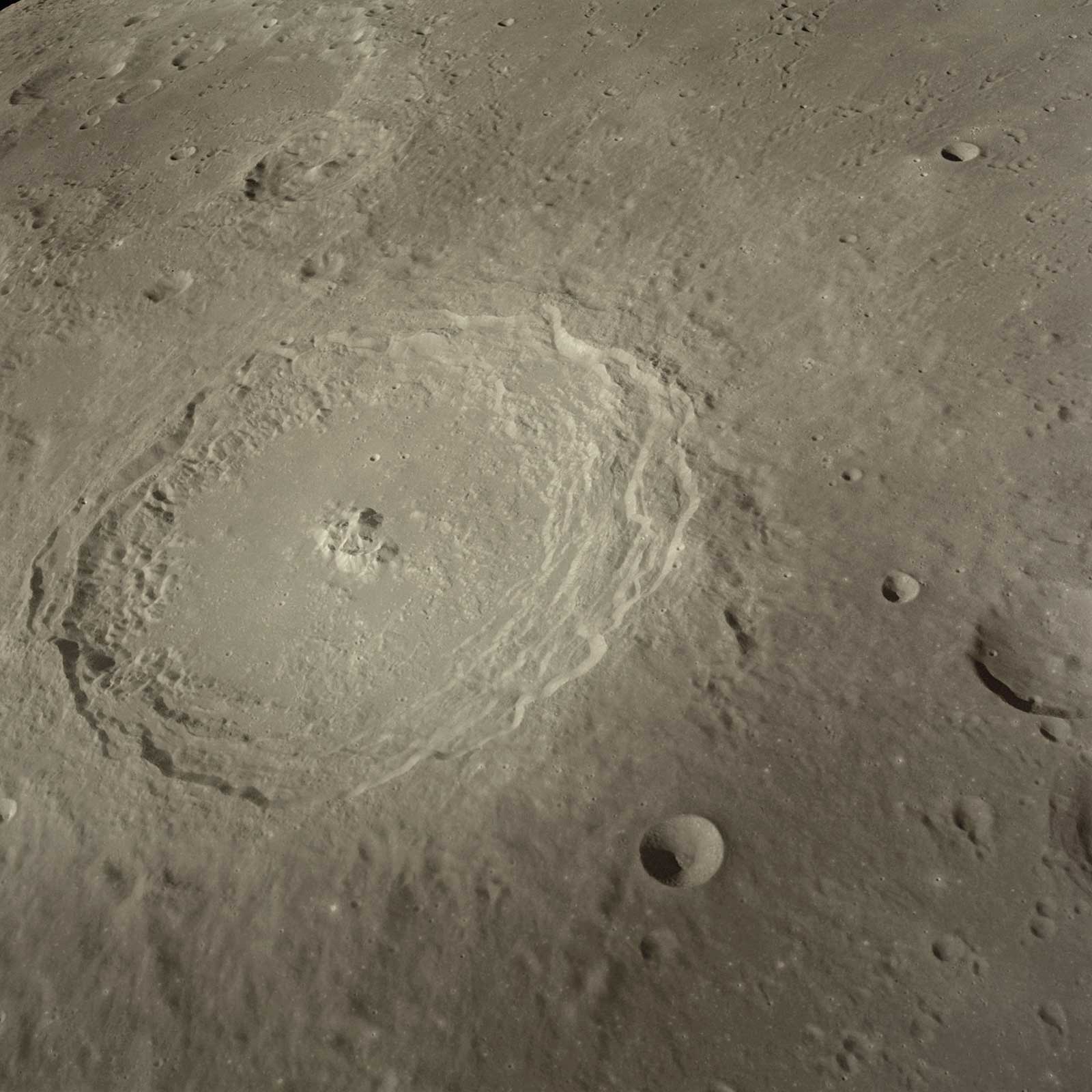

Mission Control’s viewing-room spectators broke into cheers and loud applause. Apollo 8 was in a 168.5 by 60 mile orbit on this day before Christmas. “What does the old Moon look like from 60 miles?” asked CapCom. “Essentially gray; no color,” said Lovell, “like plaster of paris or a sort of grayish beach sand.” The craters all seemed to be rounded off; some of them had cones within them; others had rays. Anders added: “We are coming up on the craters Colombo and Gutenberg. Very good detail visible. We can see the long, parallel faults of Goclenius and they run through the mare material right into the highland Material.”

During the second egg-shaped orbit the astronauts produced the Moon on black-and-white television (color would not come until Apollo 10). It proved to be a desolate place indeed, a plate of gray steel spattered by a million bullets. “It certainly would not appear to be an inviting place to live or work”, Borman said later.

On the third revolution the SPS engine fired nine seconds to put the spacecraft into a circular orbit, 60.7 by 59.7 miles, where it would stay for sixteen hours longer (each orbit lasted two hours, as against one and one-half hours for Earth).

At 8:40 p.m. the astronauts were on television again. First, they showed the half Earth across a stark lunar landscape. Then, from the other unfogged window, they tracked the bleak surface of the Moon. “The vast loneliness is awe-inspiring and it makes you realize just what you have back there on Earth”, said Lovell. The pictures aroused great wonder with an estimated half billion people vicariously exploring what no man had ever seen before.

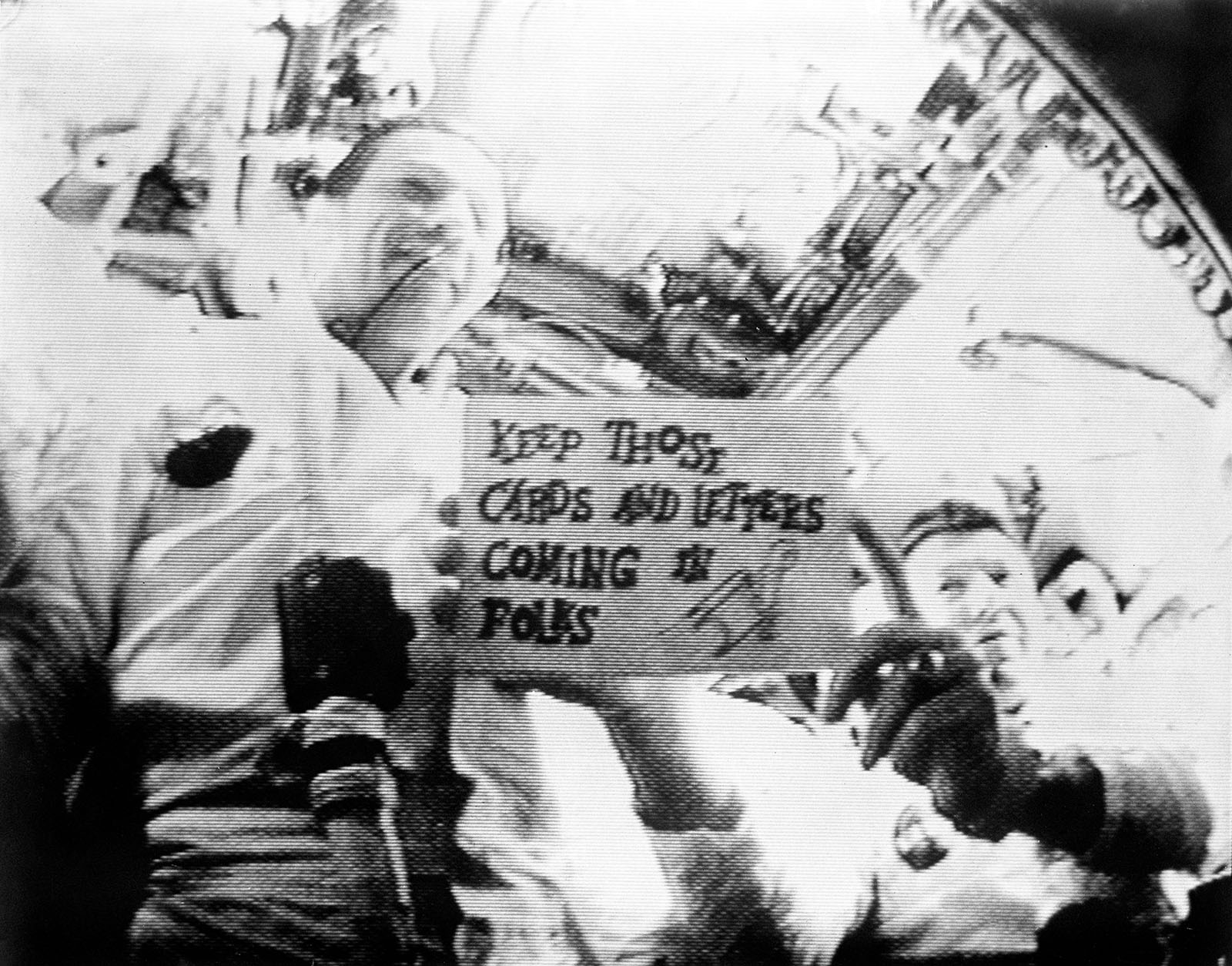

”For all the people on Earth,” said Anders, “the crew of Apollo 8 has a message we would like to send you.” He paused a moment and then began reading:

In the beginning God created the Heaven and the Earth.

After four verses of Genesis, Lovell took up the reading:

And God called the light Day and the darkness he called Night.

At the end of the eighth verse Borman picked up the familiar words:

And God said, Let the waters under the Heavens be gathered together unto one place, and let the dry land appear; and it was so. And God called the dry land Earth; and the gathering together of the waters He called seas; and God saw that it was good.

The commander added: “And from the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas, and God bless all of you-all of you on the good Earth.” It was a time of rare emotion. The mixture of the season, the immortal words, the ancient Moon, and the new technolgy made for an extraordinarily effective setting.

A LUNAR CHRISTMAS

”At some point in the history of the world”, editorialized The Washington Post, “someone may have read the first ten verses of the Book of Genesis under conditions that gave them greater meaning than they had on Christmas Eve. But it seems unlikely ... This Christmas will always be remembered as the lunar one.”

The New York Times, which called Apollo 8 “the most fantastic voyage of all times”, said on December 26: “There was more than narrow religious significance in the emotional high point of their fantastic odyssey.”

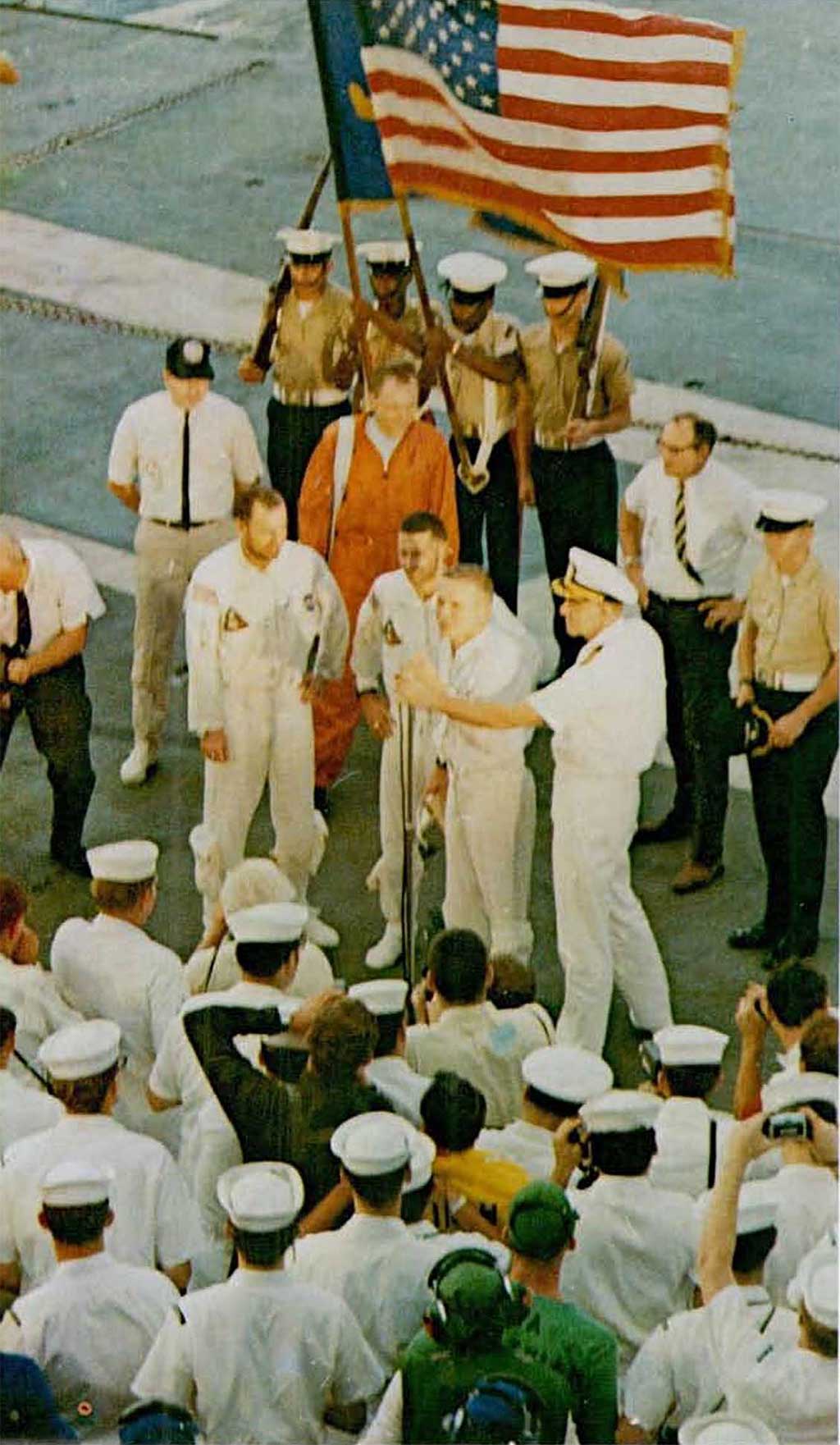

As Apollo 8 began its tenth and last orbit, CapCom Ken Mattingly told the astronauts: “We have reviewed all your systems. You have a GO to TEI” (trans-earth injection). This time the crew really was in thrall to the SPS engine. It had to ignite in this most apprehensive moment of the mission, else Apollo 8 would be left in lunar orbit, its passengers’ lives measured by the length of their oxygen supply. Ignite it did, in a 303-second burn that would effect touchdown in just under 58 hours. Apollo 8 reentered at 25,000 mph and splashed down south of Hawaii two days after Christmas.

The stupendous effect of Apollo 8 was strengthened by color photographs published after the return. Not only was the technology of going to the Moon brilliantly proven; men began to view the Earth as “small and blue and beautiful in that eternal silence”, as Archibald MacLeish put it, and to realize as never before that their planet was worth working to save. The concept that Earth was itself a kind of spacecraft needing attention to its habitability spread more widely than ever.

During the last week of 1968 the Associated Press repolled its 1278 newspaper editors, who overwhelmingly voted Apollo 8 the story of the year. Time discarded “The Dissenter” in favor of Borman, Lovell, and Anders; and a friend telegraphed Frank Borman, “You have bailed out 1968.”