From Designs To Structures

Making Big Sandpiles

Before thousands of skilled craftsmen could begin turning these unique designs into structures, the Launch Operations Center had to prepare the sites, dredge access channels, and fight mosquitoes. The Gahagan Dredging Corporation of Tampa won the contract to clear the land and dredge an access channel to the site of the vertical, or as it was soon to be called, the vehicle assembly building (VAB). The sand, dredged up by the Gahagan crews, was deposited on the projected sites of the VAB, the crawlerway, launch pad 39-C (shortly to be redesignated pad A)*, and the causeway over the Banana River.

Gahagan started work on 31 October 1962 by clearing the land in the VAB area. Dredging began a week later. By the time the contract was awarded, Gahagan had three dredges at work and had already moved 20,600 cubic meters of fill. One part of the work involved the clearing of surface growth, ranging from palmetto scrub to orange trees, and the stripping away of undesirable surface material from the construction sites. Specialized equipment helped to speed this job. One device, a palmetto plow, pulled up trees by their roots, shook off the dirt, and piled them for burning. Bulldozers with heavy teeth on the blades knocked down whole rows of trees and brush, pushing them into piles to dry before burning. The bulldozers cleared some 2.5 square kilometers of land in this manner, while other earthmoving equipment removed 894,400 cubic meters of soft sand and muck.1

The second, and perhaps larger, part of Gahagan’s job was dredging a barge canal 38 meters wide, 3 meters deep, and 20 kilometers long from the original Saturn barge channel in the Banana River to a turning basin near the VAB. The canal would serve barges bringing in the first and second stages of the Saturn V. Gahagan dredged a channel to pad A so that barges could deliver material directly to the LC-39 construction site.

During the dredging operations, the powerful hydraulic pumps coughed up 6,876,000 cubic meters of sand and shell for fill. A major portion of it went into the 57-meter-wide, 2-meter-high crawlerway, which would stretch more than 4.8 kilometers from the VAB to pad A.

Out at the pad site, the pumps piled a pyramid of sand and shell 24.4 meters high, one of the highest recorded pumping operations. All the while, draglines, bulldozers, and other earth-moving equipment molded the mound into the approximate shape of the launch pad. Subsequent measurements revealed that this outsized sandpile had settled 1.2 meters and properly compressed the soil beneath. Bulldozers then removed part of the pile to bring the fill to the proper elevation.2

A final inspection of the land clearing, channel dredging, and fill in early September 1963 showed that Gahagan had completed all work on the contract. About six months after the completion of the fill for pad A, Gahagan began pumping and piling hydraulic fill for launch pad B and for the causeway from Cape Canaveral to Merritt Island east of the industrial area.3

- At the time of the original siting of launch complex 39, the three projected launch pads were designated in accordance with standard Missile Test Center practice from north to south as pads A, B, and C. In January 1963, to bring the identification system in line with construction and operational use schedules, the pad designations were reversed, the southernmost becoming pad A. Early documentation carries the original designations; the revised designations are used hereafter in the text. C. Bidgood, Chief, Facilities Off., “Reidentification of Launch Complex 39 Launch Pads,” 7 Jan. 1963.

NASA Declares War - On Mosquitoes

The Spaceport News had its share of sensational headlines during 1963, especially in May when Astronaut Gordon Cooper took Faith 7 into an earth orbit on a Mercury-Atlas launch vehicle from pad 14. But none quite reached the unique quality of a headline in the 8 August issue: “Peaceful NASA Declares War - On Mosquitoes.”4 It may well have been the most necessary, well-executed, and successful war in American history. For reasons of health and comfort, the mosquito population had to be reduced before workers could begin any sustained outdoor work during the prime mosquito season from April to late October. In the past, epidemics of malaria, yellow fever, and dengue (an infectious fever prevalent in warm climates) - all spread by mosquitoes - had periodically retarded the development of Florida. The discovery and application of successful methods of mosquito control had been one of the factors responsible for the state’s rapid development in relatively recent years.

Almost from the outset, the mosquito figured prominently in NASA’s operations. LVOD’s Deputy Chief of the Mechanical, Structural, and Propulsion Office, Robert Gorman, spoke of the early days: “The mosquitoes were so bad.... Everyone wore long shirt sleeves and gloves, even in the summer.... In fact, one fellow with sensitive skin really got chewed up. He stayed in Huntsville after that.” In recalling the first Redstone launch from the Cape, Gorman remarked: “You couldn’t wear a white shirt. The mosquitoes would be so thick they’d turn it black.” In an interview two years later, James Finn, who had come to the Joint Long Range Proving Ground in 1951 and joined the original Debus team in May 1954, said that “the mosquitoes were a hazard - but so was the mosquito repellant. . . . If any got on our badges, it rubbed our pictures off.”5

The problem was at first almost unbelievable to all but former residents of the area. One acre of salt marsh was easily capable of producing 50,000,000 adult mosquitoes within a week after a heavy rainfall. The “landing rate” in bad areas was often more than 500 mosquitoes on a person in one minute. In 1962, two scientists from the Florida Entomological Research Center in Vero Beach collected with hand nets 1.6 kilograms of live mosquitoes in just one hour.

By April 1963, the Subcommittee on Mosquito Control of the Joint Community Impact Coordination Committee [see chapter 5-4] agreed upon a cooperative program using the services of the county, state, Air Force Missile Test Center, and the Launch Operations Center. The program sought both temporary and permanent control. At the time, the main breeding grounds of the salt-marsh mosquito included 57.7 square kilometers in northern Brevard County and 4.3 square kilometers in southern Volusia County. Within the Merritt Island Launch Area were also hundreds of acres capable of producing fresh-water mosquitoes.

The temporary control measures consisted of ground and aerial spraying of insecticide. The most effective permanent control on the Merritt Island Launch Area consisted of the construction of dikes to flood breeding areas during the peak summer months. With the flooding of marshes, the minnow population increased and mosquito eggs and larvae declined.

The Brevard County Mosquito Control District also agreed to continue work at the Merritt Island Launch Area. The county provided four draglines, two spray planes, and a helicopter for inspection purposes. The Launch Operations Center and the Air Force Missile Test Center provided two draglines and one bulldozer to accelerate the permanent control work that the county was doing. The Launch Operations Center supplied the insecticide and operated the ground fogging equipment. The State of Florida provided direct financial aid and scientific research. The master plan had originally estimated six years to accomplish reasonable mosquito control in the Merritt Island Launch Area. Fortunately the program moved much faster than that.6

Contracting for the VAB and the LCC

Four of the world’s most unique buildings were to go up on Merritt Island during the succeeding years, two at one end of launch complex 39, two in the industrial area five miles south. While other structures, such as the more traditionally designed headquarters, were to be known at the center by their full titles, these four shortly became known by acronyms: the vehicle assembly building as the VAB, the launch control center as the LCC, the central instrumentation facility as the CIF, and the operations and checkout building as the O & C building. This last building was also called the manned spacecraft operations building.

The day after his visit to Florida in September 1962, President Kennedy stated at Rice University Stadium in Houston:

In the last 24 hours, we have seen facilities now being created for the greatest and most complex exploration in man’s history. We have felt the ground shake and the air shattered by the testing of a Saturn C-1 booster rocket.... We have seen the site where five F-1 rocket engines... will be clustered together to make the advanced Saturn missile, assembled in a new building to be built at Cape Canaveral as tall as a 48-story structure, as wide as a city block, and as long as two lengths of this field.7

No doubt many of the Rice engineers and students appreciated the remarks of the President. The concept, however, still stretched beyond the imagination of the average American. He could not picture a building so huge that the Rose Bowl or the Yankee Stadium would fit on the roof. Yet this was what URSAM planned for the vehicle assembly building.

During the first half of 1963, the Corps of Engineers was still acquiring land for the spaceport and simultaneously awarding contracts for continued site preparation and utility installations. Dredging operations to provide fill for the VAB, one launch pad, and the Banana River causeway were proceeding on schedule. In the industrial area, ground-breaking ceremonies were held in January on the site of the operations and checkout building, and the Corps of Engineers awarded a contract for the construction of primary utilities to provide for a water distribution system, sewer lines, an electrical system, a central heating plant, streets, and hydraulic fill for the Indian River causeway to connect the industrial area on Merritt Island with the Florida mainland. During this same period, the Launch Operations Center began awarding the first construction contracts for structures in the industrial and LC-39 areas.

The national goal of accomplishing the manned lunar landing “before this decade is out” dramatically affected the entire building program. With a deadline, scheduling became critical. At the beginning of 1963, the Office of Manned Space Flight’s “official flight schedule” called for the launch of the first developmental Saturn V in March 1966 and of the first manned Saturn V in June 1967.8 Meeting these dates was contingent upon the concurrent development of the Saturn V launch vehicle, the Apollo spacecraft, and launch facilities, and more particularly on the timely delivery of flight hardware to the launch center.

Of more immediate concern was the construction of launch facilities and checking them out many months before the first Saturn V launch. The first of December, 1965, was the most important date - the date when the launch complexes had to be ready for use. This in turn required that a number of facilities be ready by May 1965 to provide time for checking out and testing the launch complexes. Working backward from this date, LOC developed, and periodically revised, detailed schedules for completion of the construction and testing of each facility on launch complex 39 and in the industrial area. The demands of this tight schedule influenced construction as much as the development of the launch vehicle and the spacecraft.

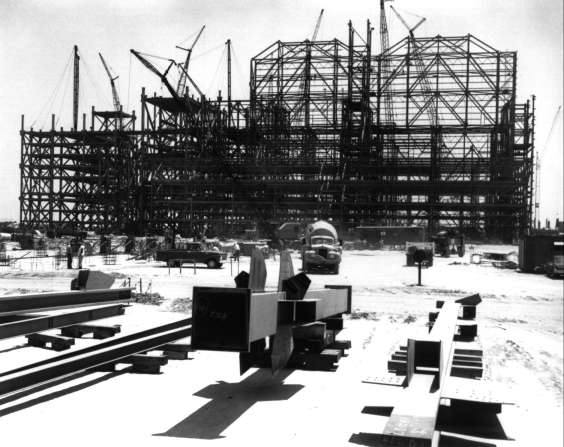

On 31 May 1963, the Corps of Engineers advertised for bids on the structural steel and the erection of the VAB framework. On 9 July Col. G. A. Finley, District Engineer of the newly established Canaveral District of the Corps of Engineers, acting as agent for NASA, and officials of the American Bridge Division of U.S. Steel Corporation, Atlanta, signed the largest single contract NASA had yet awarded for work in the Cape area. This contract, in the original amount of $23,534,000, called for furnishing more than 45,000 metric tons of structural steel and the erection of the skeleton framework of the VAB, with completion by 1 December 1964. Workmen were busy at the site the day the contract was signed. The Blount Brothers Corporation of Montgomery, Alabama, signed an $8,000,000 contract on 11 July 1963 to provide the steel and concrete foundations and flooring of the VAB, with completion by 1 May 1964. The Blount firm also started work on the day of the signing.9

Laying the Foundations

Providing a firm foundation for construction on sandy soil had been one of the early design problems. Max O. Urbahn, head of one of the four firms in the design consortium, spoke of a second problem: “We were faced with the fascinating possibility that the shape of the building might make it react like an immense box kite; it could blow away in a high wind . . . .”10 The solution to both problems was to drive thousands of piles, steel pipes 41 centimeters in diameter, through the subsoil until they rested on bedrock. These served to anchor the building as well as to prevent the structure from sinking into the ground.11

The building stood only a few feet above sea level and near the ocean. Salt water, saturating the subsoil, reacted with steel piling to create an electrical current. To prevent this electrolytic process from gradually eating away the steel pipe, workmen grounded the piling by welding thick copper wire to each pile and connecting the wires to the steel reinforcing bars in the concrete floor slab. Until this was done, the VAB could lay claim to being the world’s largest wet cell battery.12

Blount Brothers moved rapidly to assemble pile-driving equipment, steel piling, and workmen at the work site. They drove the first piles on 2 August 1963 and by 15 August had driven 9,144 meters of piling in the low bay area. The pipe for the piling came in 16.8-meter lengths, and welders had to join three and sometimes four lengths of pipe together to make up a single pile. To speed the work, Blount Brothers had their workmen weld at night and drive piles, which required better visibility, during the day. At the peak of activity, ten pile drivers were in action. Three of them were new, electrically driven, vibratory drivers that literally jigged the pilings into the ground. When the piles reached the first thin stratum of limestone at about 36 meters, steam- or diesel-driven pile drivers took over and pounded the piles into the bedrock, which ranged from 46 to 52 meters below the sandy surface. Although there were minor delays due to inclement weather - a week of unrelenting high winds and torrential rains brought all construction to a standstill in mid-September - the work on the foundations moved steadily ahead. The last of the piling was down on 3 January 1964, just five months after drivers pointed the first pile into the bedrock.13

As the pile drivers moved on, another group of Blount Brothers workmen moved in to erect the forms and place the reinforcing bars for the concrete pile caps and to bond the piles electrically to the reinforcing bars. To an observer in a helicopter, the VAB foundation site began to resemble a huge honeycomb with the concrete pile caps rapidly dividing the area into series of cells or boxes.14 As soon as the concrete had set in a series of the pile caps, workmen removed the forms and replaced any fill removed in the course of work. Then they poured a layer of crushed aggregate into the boxes and poured the asphalt and concrete floor slab on top of the aggregate. All told, Blount Brothers poured 38,200 cubic meters of concrete for pile caps and floor slab before the foundation was completed in May 1964.

Even before sinking the first pile of the foundation and beginning the steel framework of the VAB, the Corps of Engineers had taken the initial step toward awarding a contract for three large bridge cranes in the VAB.15 A 175-ton crane with a hook height of about 50 meters would run the length of the building and would traverse both the low bay and high bay areas above the transfer aisle. Two other cranes, with a 250-ton capacity and hook height of approximately 140 meters, would be capable of movement from an assembly bay on the opposite side. Although bridge cranes of this capacity are not unusual in heavy industry, the invitation for bids spelled out unique requirements for precision, smoothness, and control of their vertical and horizontal movement. The cranes would cost about $2,000,000. Colby Cranes Manufacturing Company of Seattle won the contract and agreed to have the cranes ready for final test on 1 September 1965.16

Structural Steel and General Construction

While work on the foundations and floor slab of the VAB was progressing rapidly during the latter half of 1963, there was little on-site activity on the part of the structural steel contractor. However, as the American Bridge Division began mobilizing its work force and assembling its equipment on Merritt Island, United States Steel plants throughout the country were fabricating the carbon steel plate and structural shapes required for the building’s framework.17

On 4 October 1963, the Corps of Engineers advertised for bids on general construction and outfitting in the VAB area. In addition to completion of the VAB (including outfitting only high bays 1 and 3), the work covered general site preparation, roads and utility installations in the area, the construction and outfitting of the VAB utility annex and the launch control center - both good-sized buildings in their own right - and of two other support buildings, one for high-pressure-gas storage and the other for paint and chemical storage. Estimators set the price of the VAB alone at $52,000,000. The Corps of Engineers scheduled completion for 1 January 1966.18

A combine of three South Gate, California, construction-engineering companies - Morrison-Knudsen Company, Inc., Perini Corporation, and Paul Hardeman, Inc. - won the contract on 16 January 1964 with a bid of $63,366,378.19 It was not long, however, before the contract grew considerably. On 9 March the South Gate combine assumed administration of the American Bridge Division’s contract for structural steel work on the VAB and the Colby Cranes contract for fabrication, installation, and testing the three large bridge cranes, as the latter two companies became subcontractors to the South Gate group. With the absorption of these two earlier contracts, the Morrison-Knudsen, Perini and Hardeman general construction and outfitting contract reached a value of $88,743,386.20 Although both American Bridge and Colby continued at their respective jobs until their completion, all VAB area brick-and-mortar construction was now under the direction of a single contractor.

With steel column sections and other structural steel arriving at the job site, erection of the framework began in January 1964 in the low bay area. By this time the original contract date for completing the structural steel (1 December 1964) had given way to a completion date of 7 March 1965. The job was a rather straightforward one although, because of the building’s unique requirements, it appeared that the structure was being built wrong-side out. Because of the height of the assembly bay door openings - two on each side of the building - the horizontal stiffening structure had to be installed on the interior of the building, parallel to the transfer aisle, rather than along the exterior sides.21

Less than a month after steel erection began, the general construction contractor, Morrison-Knudsen, Perini and Hardeman, started work in the VAB area. After setting up a temporary office, warehouse, and concrete mixing plant on the job site, the contractors began compacting and stabilizing the crawler erection area, preparing the erection site for one mobile launcher, excavating for the crawlerway base, and excavating for the foundation floor slab of the launch control center. Contractors completed the crawler assembly area by 11 March and the mobile launcher area by 1 June.22

Meanwhile, Morrison-Knudsen, Perini and Hardeman had also begun work in February on the high-pressure-gas storage building, the road system in the VAB area, the instrumentation and communication duct banks and tunnels from the launch control center to the crawlerway, and the foundation work for the control center itself. In March work started on the water distribution and storage system, on the sewage plant and sewer system, and on the electrical distribution system. In April construction began on the VAB utility annex, on the paint and chemical storage building, and on the VAB area crawlerways.23 Thus, by the time the ironworkers of the American Bridge Division had progressed far enough with erection of the VAB framework to allow the Morrison-Knudsen, Perini and Hardeman workmen access to the building, almost all of the other construction in the general area was moving ahead. The combine started work in the northwest corner of the low bay in April.24

From this time on, employees of the two contractors worked jointly in the building, with the general construction men following closely behind the ironworkers. Joint occupancy was necessary if the building and related facilities were to be completed on schedule. Since contractors in widely scattered parts of the country worked on different parts of the total job, construction chiefs on Merritt Island had to test components regularly to see if they fitted and worked together. These so-called “fit tests” became important procedures in the early stages of construction. The installing of many pieces of vehicle-related ground support equipment - a necessity for facility checkout - had to await completion of most of the general construction.

The same combine of California construction-engineering companies built the launch control center as part of the VAB contract. URSAM had decided on a distinctively shaped four-story building adjoining the VAB on the southeast and connected with it by an enclosed bridge. The ground floor contained offices, cafeteria, and dispensary, the second floor telemetry and radio equipment. Firing rooms occupied the third floor, and the fourth floor had conference rooms and displays.25

The original plan called for four rectangular firing rooms, 28 by 46 meters; one was never to be equipped. When completed, the firing rooms contained similar equipment set up on four levels. The first level took up over two-thirds of the room and would ultimately contain computers and five rows of 30 consoles each. Two rows of consoles (27 in one, 25 in the other) would fill the second level. The third level would contain the consoles of the Kennedy Space Center Director and other major officials. To the left of these consoles, two diagonal rows of seats with telephones and listening devices, but no control equipment, would provide a close-up view of operations for technical experts not directly involved in the launch. On the top level, a glassed-in triangular room would give visiting dignitaries a like view. They could either watch activities in the firing room or look out the windows at the launch pads. These double-paned windows extended the full width of the rear of the firing room and contained a special heat - and shock-resistant glass. Outside, large vertical louvers, resembling huge venetian blinds, could be closed in a few moments for further protection.

Cleo and Dora Visit the Cape

The nearby passage of hurricanes Cleo in late August and Dora in early September 1964 caused an estimated $35,000 worth of damage, but a delay of only three days. The editor’s “Spotlight” in the 3 September edition of the Spaceport News reported the lack of major damage to NASA facilities and dispensed credit widely - from the people who drew up the storm plans to the man who laid the last sandbag in place a few hours before Cleo swept by. That everything went off without a hitch reflected favorably on the advance planning. “It was a team that got the job done,” the editor wrote. “Everyone involved directly in securing operations had his work to do, and did it with the minimum of hubbub.”26

The editor singled out “Hurricane” Jones. A KSC engineer with the Instrumentation Division’s acoustic and meteorological section, bachelor Jones had volunteered to ride out the storm in the huge launch control center at complex 37, gathering weather data. From 10 a.m. on Thursday until relief came at 7:30 the next morning, he recorded winds that peaked at 112.6 kilometers per hour. The reluctant hero admitted that he had misgivings during his lonely vigil, even though he had thought the launch control center looked like the safest place in the vicinity.27

VAB Nears Completion

At the beginning of October 1964, a survey revealed that the construction force on all contracts at the new Merritt Island spaceport had reached a total of 4,300, with about 500 more equipment installers at work. At that time, KSC had 1,670 federal employees, 1,902 support services contractor employees, and 863 employees of launch vehicle contractors. The Florida Operations Division of the Manned Spacecraft Center (deeply involved in Project Gemini, which would launch its first manned orbital flight the following March, and just becoming concerned with the activation of Apollo spacecraft facilities) had a force of 502 federal employees and 1,042 persons in the employ of contractors. Overall employment at Cape Kennedy and Merritt Island was expected to exceed 15,000 by 1 January 1965.28

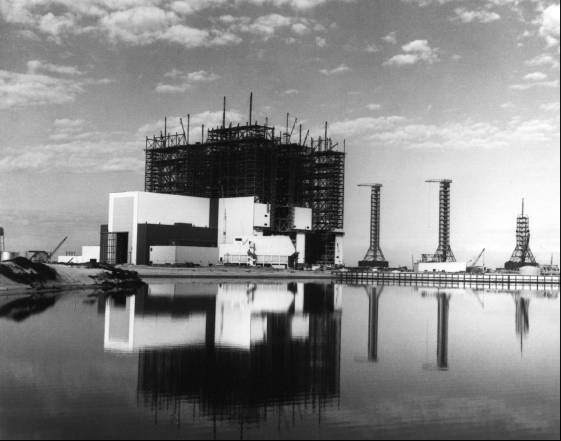

By Christmas of 1964, the ironworkers had erected nearly 38,000 metric tons of structural steel in the VAB, reaching the 128-meter level in all towers. The LCC building was nearing completion, although interior mechanical work and the installation of electrical fixtures continued on all four floors. The VAB utility annex was also nearing completion, with boiler stacks and skylights completed and installation of mechanical and electrical equipment continuing. Workers had finished the high-pressure-gas storage building on 2 October. The rest of the area facilities were all nearing the end of brick-and-mortar construction, although much installation and outfitting remained.29

Structural parts for the first of the extensible work platforms in the high bays (five pairs of platforms in each high bay) had arrived at the VAB site. Workmen assembled these platforms outside the VAB because of their size, approximately 18 meters square and up to three stories tall, and then moved them inside for mounting on the framework of the VAB. They would be vertically adjustable. Since they were of cantilever design, they could extend horizontally about 9 meters from the main framework of the building to surround the launch vehicle in the high bay.30

As construction and outfitting continued into 1965, the vertical assembly building got a new name but not a new acronym. It was still the VAB, but now officially the vehicle assembly building, as of 3 February 1965. The new name, it was felt, would more readily encompass future as well as current programs and would not be tied to the Saturn booster. The Office of Manned Space Flight formally approved the change in September 1965, but individuals at the facility continued to use both names interchangeably.31

The Colby Cranes Manufacturing Company had completed shop testing all three bridge cranes in Seattle and had shipped the 175-ton crane to the VAB site. By the end of January 1965, the two 250-ton bridge cranes had followed. They would soon be ready to install. In fact, countless details of the largest building in the world were approaching completion.32

Erection of the VAB’s structural steel framework reached the top level of 160 meters at the end of March, and preparations began for the traditional topping-out ceremony. A 3,600-kilogram, 11.6-meter-long steel I-beam, painted white and bearing the NASA symbol and the insignia of the American Bridge Division of the United States Steel Corporation, stood in front of several of the NASA buildings at KSC during early April to allow NASA and contractor employees to sign their names on it. The signed beam then went under the roof of the VAB over the transfer aisle.33

Construction in the Industrial Area

While the vehicle assembly building and other facilities moved steadily toward completion at LC-39, the industrial area began to take shape to the south. Preliminary to any actual construction, the Azzarelli Construction Company had completed ground work for the operations and checkout building in early November 1962.34 Azzarelli had used the surcharging method in preparing the soil by piling sand on the construction site until its weight was approximately equivalent to the weight of the proposed structure. The heavy surcharge compressed the underground layers of clay and coral, squeezing out liquids. The contractors used piling under later parts of the building, as well as for all other buildings on Merritt Island.

On 16 January 1963, the Paul Hardeman and Morrison-Knudsen combine, which would also construct the basic utility systems in the industrial area, signed a contract in the amount of $7,691,624 for the construction of the operations and checkout building. By the end of February, men were clearing the construction site and the right of way to it and removing excess surcharge material.35 The O & C building was to undergo continuous addition, modification, and alteration during the succeeding five years. Some contractual changes reflected planned phasing of construction over several fiscal years’ funding; others, the evolving design of the spacecraft; some were intended to improve the original design of the building.

Early criteria for the building had envisioned flight crew training equipment among the astronaut facilities. Early in 1964, however, the Manned Spacecraft Center’s Flight Crew Support Division in Houston decided on a separate building for crew training. To assist in the preparation of the separate structure, it forwarded criteria and sketches of a similar facility located at the Manned Spacecraft Center. Other changes from the initial O & C building design included additions to the administrative and engineering area, to the four-story laboratory and checkout section, and to the assembly and test areas. Three firms in joint contract, Donovan Construction, Power Engineering, and Leslie Miller, Inc., completed these additions.36

In September 1964, designers began drawings for a clean room, or white room, for the Gemini program. This was a dust-free room with high quality temperature and humidity controls to prevent contamination of the space vehicle. The air intakes would have special filters. All persons who entered the room would wear clothing resembling surgical uniforms. To be located in the O & C building’s assembly and test area, the room was built by S. I. Goldman of Winter Park, Florida.37

The O & C building, a multi-storied structure of approximately 17,200 square meters, contained as much flexibility as the Apollo spacecraft that it would test. A high bay, 68.2 meters long and 30.5 meters high, and an adjacent 76.5-meter-long low bay accommodated the three-man Apollo capsule. Two altitude chambers were prominent fixtures in the high bay. In these tanks, each 17 meters high and 10 meters in diameter, KSC engineers would check out the command and service modules and the lunar module. After pumps had evacuated the air from the chambers, the Apollo modules were checked out in a near vacuum. Two airlocks, measuring 2.6 meters in height and width, provided access to each chamber. They also housed the rescue teams. Should a loss of oxygen occur in the spacecraft, the physiological effects on the crewmen would be the same as in space. The rescue teams would have to move fast, after rapidly pressurizing the chamber to a simulated altitude of 7,600 meters.38 After testing, the mated spacecraft components - the command module, the lunar excursion module, and the service module - would be moved from the integrated test area to the VAB in a vertical attitude, ready for stacking on top of the launch vehicle.39

The headquarters building, just west of the O & C building and a much less complicated structure, went up in two phases: the central structure, measuring 80 by 72 meters, first, and the east and west wings later. The building stood three stories high, except in the front where a fourth floor contained top administrative offices. The main section of the building extended east and west. The original plan called for four arms stretching to the south. Later on, the east and west additions brought with them two other southward extensions. The Franchi Construction Company of Newton, Massachusetts, which had begun work on the fluid test complex in mid-April 1963, started on the headquarters building in February 1964. On the day that the headquarters building got under way, the Blount Brothers Construction Corporation began the two buildings that comprised the central instrumentation facility.40

The Florida Operations team of the Manned Spacecraft Center was the first organization to occupy NASA’s new facilities on Merritt Island. Most of the 1,270 MSC and contractor employees who moved over from the Cape in September and October 1964 took new offices in the O & C building. Although heavily committed on the Gemini program, representatives of Florida Operations coordinated with contractor personnel and KSC in determining Apollo checkout requirements. By the following year the launch team had formulated a ground operations requirements plan. Some of the requirements, anticipated in early 1963 when the facilities were designed, no longer appeared necessary, e.g., Houston had decided to pack the Apollo parachutes at the factory rather than in Florida. Houston officials were coming to believe that, because of the spacecraft’s complexity, it was undesirable to postpone major operations until the prelaunch checkout. As much as possible should be accomplished at the factory. This view would alter considerably the scope of Apollo operations in Florida.41

Ceremonies at Completion

With construction nearing completion, Kennedy Space Center celebrated two formal dedications in the spring of 1965. On 14 April, 30 dignitaries came for the topping-out ceremonies at the vehicle assembly building: officials of KSC, the Corps of Engineers, the newly renamed Eastern Test Range, U.S. Steel, the Morrison-Knudsen, Perini, and Hardeman consortium of contractors, and the design team of Urbahn-Roberts-Seelye-Moran. In a brief address, Debus stated:

This building is not a monument - it is a tool if you will, capable of accommodating heavy launch vehicles. So if people are impressed by its bigness, they should be mindful that bigness in this case is a factor of the rocket-powered transportation systems necessary to provide the United States with a broad capability to do whatever is the national purpose in outer space....42

In a less formal, but equally effective way, Ben Putney summed up the workers’ feelings when he quipped: “This is the biggest project we’ve ever worked on. There just ain’t nothing bigger!” American Bridge’s senior construction superintendent, John Pendry, said of the VAB: “You can’t call it a high-rise building, it’s more like building a bridge straight up.”

Although workers had topped out the structural steel in the VAB, the work was far from finished. Steven Harris, VAB project manager, noted that one of the biggest tasks was keeping up with evolving equipment as the work went along. He remarked: “The VAB was designed and is being constructed concurrently with the development of the Saturn V vehicle, and any changes made on the vehicle or its support equipment may require changes in the building.”43 At the time he was speaking, designers had already incorporated some 200 changes into the VAB since construction began, the most recent being modification of the extensible platforms as required by the final design of the mobile launcher.

The formal opening of KSC headquarters on 26 May provided another opportunity for ceremonies. Prior to the formalities, a 40-piece Air Force band entertained the guests. Maj. Gen. Vincent G. Huston, Commander of the Air Force Eastern Test Range; Maj. Gen. A. C. Welling, head of the Corps of Engineers, South Atlantic Division; and Col. W. L. Starnes, Canaveral District Engineer, shared the podium with Debus, who thanked the Administration, the Congress, NASA, and the American people for the faith they had placed in the KSC team. Then he handed American and NASA flags to members of the security patrol who raised them to the top of the pole in front of the new headquarters.44

At the same time, the people who were going to support, maintain, and operate these facilities and their equipment had begun to move in. By mid-September “Operation Big Move” had brought 7,000 of KSC’s civil service and contractor employees from scattered sites at Cocoa Beach, the Cape, and Huntsville to Merritt Island, mostly to the industrial area; 4,500 more would move to Merritt Island during the following months, mostly into the VAB. During 1965 the civil service personnel at KSC rose from 1,180 to more than 2,500, chiefly through the addition of the Manned Spacecraft Center’s Florida Operations and the Goddard Space Flight Center’s Launch Operations Division; the latter specialized in unmanned launches.45 Even more significant for many than the physical move was the psychological move from the “pads where they had their hands in the operation” to desks where they directed the actions of others.

This description of the spaceport’s construction has emphasized the material and the contractual. A later chapter will discuss the intermittent walkouts that made some wonder if the contractors would ever finish. This chapter has dealt little with the human side of the workmen who slaved and sweated and suffered - and in a few instances died as a result of accidents. On 4 June 1964, workers were stacking concrete forms for the third floor deck in the low bay area of the VAB. Apparently, the forms became overloaded and collapsed. Five men fell and were injured, two seriously. A month later, on 2 July 1964, Oscar Simmons, an employee of American Bridge and Iron Company, died in an accidental fall from the 46th level of the VAB. On 3 August 1965, lightning killed Albert J. Treib on pad B of launch complex 39.46

To some, construction at KSC was just another job. Others, however, were keenly aware of the contribution they were making to the task of sending the first man to the moon and bringing him back safely.

ENDNOTES

- LOC, “Construction Progress Reports,” 6 Nov. 1962, p. 5; 27 Nov. 1962, p. 5; 10 July 1963, p. 2.X

- Spaceport News, 31 Oct. 1963, p. 4.X

- "Construction Progress Reports,” 15 June 1963, p. 7; 13 Sept. 1963, p. 1; D. E. Eppert, Chief, Construction Div., Canaveral Dist., Corps of Engineers, to J. J. Frangie, with attachment: “Tabulation of Contracts Supervised by the Corps of Engineers for Construction of Complexes 34 and 37 as Well as Work on Merritt Island for NASA Facilities” (hereafter cited as Tabulation of Corps of Engineers Contracts).X

- Spaceport News, 8 Aug. 1963, pp. 4-5.X

- Ibid., 28 Feb., 8, 15 Aug. 1963, 29 July 1965.X

- Ibid., 15 Aug. 1963; “Launch Operations Progress Report,” 26 Aug. 1963.X

- John F. Kennedy, address at Rice University 24 Sept. 1962, Public Papers of the Presidents, Washington, 1963, p. 329.X

- NASA Hq., OMSF Instruction MD-M9330.001, 15 Oct. 1962, with enclosure.X

- Facilities Programing Off., Facilities Engineering and Construction Div., LOC, “Summary Project Status Report,” 29 Nov. 1963, p. III-1; Tabulation of Corps of Engineers Contracts, Sept. 1968.X

- Spaceport News, 16 Jan. 1964.X

- Corps of Engineers, South Atlantic Div., Canaveral Dist., Apollo Launch Complex 39 Facilities Handbook (hereafter cited as LC-39 Facilities Handbook), pp. 4-5.X

- Spaceport News, 16 Jan. 1964, p. 7.X

- "Construction Progress Reports,” 16 Aug. 1963, p. 9; 20 Jan. 1964, p. 11; Spaceport News, 16 Jan. 1964, 26 Sept. 1963; LC-39 Facilities Handbook, p. 15.X

- Spaceport News, 16 Jan. 1964.X

- "Summary Project Status Report,” 29 Nov. 1963, p. III-2.X

- "LOC Monthly Status Report to the Management Council, Office of Manned Space Flight,” presented by Kurt H. Debus, 24 Sept. 1963, p. 15; Summary Project Status Report, 29 Nov. 1963, p. III-2.X

- "Construction Progress Report,” 22 Nov. 1963, p. 15.X

- "Summary Project Status Reports,” 29 Nov. 1963, p. III-3; 17 Apr. 1964, p. III-2; Spaceport News, 19 Sept. 1963, p. 1.X

- "Construction Progress Report,” 29 Jan. 1964, p. 20.X

- "Narrative Project Status Report, 1-30 Apr. 1964,” p. I-9.X

- "Construction Progress Report,” 20 Jan. 1964, pp. 10-11; LC-39 Facilities Handbook, pp.3,5.X

- "Narrative Project Status Report, 1-28 Feb. 1964,” p. I-9; “Summary Project Status Report,” 2 Oct. 1964, pp. IV-1, IV-2.X

- Detailed Construction Schedule, VAB Area Facilities, 1 May 1964, rev. 30 June 1964, with cover letter from William E. Pearson, Chief, Schedules Off., 27 July 1964 (this series of schedules, revised and issued periodically, will be cited as Detailed Construction Schedule, facility, date).X

- "Narrative Project Status Report, 1-30 Apr. 1964,” p. I-9.X

- 25. Apollo/Saturn V MILA Facilities Description, report K-V-011, p. 1-13.X

- 26. Spaceport News, 3, 10, 17 Sept. 1964.X

- 27. Ibid., 3 Sept. 1964; Jones interview.X

- Spaceport News, 8 Oct. 1964.X

- "Narrative Project Status Report, 1-31 Dec. 1964,” pp. I-4, I-5.X

- Ibid; LC-39 Facilities Handbook, pp. 9-10.X

- A. H. Bagnulo, Dir., Facilities Engineering and Construction Div., KSC, “Revised Designations for ASA Facilities,” 3 Feb. 1965; George E. Mueller, Assoc. Admin. for Manned Space Flight, to Dir., KSC, “Facility Titles, KSC,” with attachment, 8 Sept. 1965.X

- "Narrative Project Status Report,” 1-31 Jan. 1965, pp. I-3 through I-5.X

- Ibid., 1-31 Mar. 1965, p. I-2; Spaceport News, 1 Apr. 1965.X

- "Construction Progress Report,” 27 Nov. 1962.X

- Ibid., 22 Jan., 25 Feb. 1963.X

- MSC Florida Ops., “Description and Justification for Spacecraft Operations and Checkout Building,” included in John F. Kennedy Space Center, NASA Fiscal Year 1963 Estimates, Apollo Mission Support Facilities, Project 7623; “Manned Spacecraft Center Consolidated Activity Report for 16 Feb.-21 Mar. 1964,"p. 78.X

- KSC, “Project Status Report,” 1-31 Dec. 1964, p. I-39; Tabulation of Corps of Engineers Contracts, Sept. 1968.X

- Reyes interview, 24 June 1974; Chauvin interview, 24 June 1974.X

- KSC, Apollo/Saturn V MILA Facilities Description, K-V-011, p. 3-l,X

- KSC, “Technical Progress Report,” 19 Feb. 1964, p. 19.X

- Ling-Temco-Vought, Inc., “Historical Events - Calendar year 1964, Gemini and Apollo Programs and Facilities, Manned Spacecraft Center Florida Operations, Cape Kennedy and Merritt Island,” 22 Dec. 1964; Morris interview.X

- Spaceport News, 15 Apr. 1965.X

- Ibid.X

- Ibid., 27 May 1965.X

- Ibid., 13 Sept., 26 Dec. 1965.X

- KSC Weekly Notes, Miraglia, 6 July 1964; Parker, 7 June 1964; KSC, C. O. E., Report of Fatal Accident at LC-39, signed by Col. W. L. Starnes.X