The Fire That Seared the Spaceport

Introduction

The thirteenth Saturn flight (the third Saturn IB) on 25 August 1966 was the thirteenth success. It fulfilled all major mission objectives. For the first manned mission NASA had selected two veterans and one rookie. Command Pilot Virgil Ivan Grissom had flown Mercury’s Liberty Bell 7, America’s second suborbital flight, in July 1961, and Molly Brown, the first manned Gemini, in March 1965. Edward White had become the first American to walk in space while on the fourth Gemini flight, three months later. Flying with these two would be the youngest American ever chosen to go into space, Roger B. Chaffee, 31 years of age.

NASA gave Grissom the option of an open-ended mission. The astronauts could stay in orbit up to 14 days, depending on how well things went. The purpose of their flight was to check out the launch operations, ground tracking and control facilities, and the performance of the Apollo-Saturn. Grissom was determined to keep 204 up the full 14 days if at all possible.

North American Aviation constructed the Apollo command and service modules. The spacecraft, 11 meters long and weighing about 27 metric tons when fully fueled, was considerably larger and more sophisticated than earlier space vehicles, with a maze of controls, gauges, dials, switches, lights, and toggles above the couches. Unlike the outward-opening hatches of the McDonnell-built spacecraft for Mercury and Gemini flights, the Apollo hatches opened inward. They required a minimum of ninety seconds for opening under routine conditions.1

Predictions of Trouble

Many men, including Grissom, had presumed that serious accidents would occur in the testing of new spacecraft. A variety of things could go wrong. But most who admitted in the back of their minds that accidents might occur, expected them somewhere off in space.

Some individuals had misgivings about particular aspects of the spacecraft. Dr. Emmanuel Roth of the Loveface Foundation for Medical Education and Research, for instance, prepared for NASA in 1964 a four-part series on “The Selection of Space-Cabin Atmospheres.” He surveyed and summarized all the literature available at the time. He warned that combustible items, including natural fabrics and most synthetics, would burn violently in the pure oxygen atmosphere of the command module. Even allegedly flame-proof materials would burn. He warned against the use of combustibles in the vehicle.2

In 1964 Dr. Frank J. Hendel, a staff scientist with Apollo Space Sciences and Systems at North American and the author of numerous articles and a textbook, contributed an article on “Gaseous Environment during Space Missions” to the Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets, a publication of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. “Pure oxygen at five pounds per square inch of pressure,” he wrote, “presents a fire hazard which is especially great on the launching pad. . . . Even a small fire creates toxic products of combustion; no fire-fighting methods have yet been developed that can cope with a fire in pure oxygen.”3

Further, oxygen fires had occurred often enough to give safety experts cause for extra-careful procedures: at Brooks Air Force Base and at the Navy’s Equipment Diving Unit at Washington, D.C., in 1965; and at the Airesearch Facility in Torrance, California, in 1964, 1965, and 1966.4

One man saw danger on earth, from hazards other than fire. In November 1965, the American Society for Testing and Materials held a symposium in Seattle on the operation of manned space chambers. The papers gave great attention to the length of time spent in the chambers, to decompression problems, and to safety programs. The Society published the proceedings under the title of Factors in the Operation of Manned Space Chambers (Philadelphia, 1966). In reviewing this publication, Ronald G. Newswald concluded: “With reliability figures and flight schedules as they are, the odds are that the first casualty in space will occur on the ground.”5

Since Newswald was a contributing editor of Space/Aeronautics, it may well be that he contributed the section entitled “Men in Space Chambers: Guidelines Are Missing” in the “Aerospace Perspective” section of that magazine during the same month that his review appeared in Science Journal. The editorial reflects the ideas and the wording of his review. The “Guidelines” writer began: “The odds are that the first spaceflight casualty due to environmental exposure will occur not in space, but on the ground.” He saw no real formulation of scientific procedures involving safety - such as automatic termination of a chamber run in the event of abnormal conditions. “By now,” he stated, “NASA and other involved agencies are well aware that a regularly updated, progressive set of recommended practices-engineering, medical and procedural - for repressurization schedules and atmospheres, medical monitoring, safety rescue and so on, would be welcome in the community.”6

Gen. Samuel Phillips, Apollo Program Director, had misgivings about the performance of North American Aviation, the builder of the spacecraft, as early as the fall of 1965. He had taken a task force to Downey, California, to go over the management of the Saturn-II stage and command-service module programs. The task force included Marshall’s Eberhard Rees and the Apollo Spacecraft Program Manager, Joseph Shea; they had many discussions with the officials of North American. On 19 December 1965, Phillips wrote to John Leland Atwood, the President of North American Aviation, enclosing a “NASA Review Team Report,” which later came to be called the “Phillips Report.”7 The visit of the task force was not an unusual NASA procedure, but the analysis was more intensive than earlier ones.

In the introduction, the purpose was clearly stated: “The Review was conducted as a result of the continual failure of NAA to achieve the progress required to support the objective of the Apollo program.”8 The review included an examination of the corporate organization and its relationship to the Space Division, which was responsible for both the S-II stage and the command-service module, and an examination of North American Aviation’s activities at Kennedy Space Center and the Mississippi Test Facility. The former area belongs more properly to the relations of North American Aviation with NASA Headquarters, but the latter directly affected activities at Kennedy Space Center.

Despite the elimination of some troublesome components and escalations in costs, both the S-II stage and the spacecraft were behind schedule. The team found serious technical difficulties remaining with the insulation and welding on stage II and in stress corrosion and failure of oxidizer tanks on the command-service module. The “Report” pointed out that NAA’s inability to meet deadlines had caused rescheduling of the total Apollo program and, with reference to the command-service module, “there is little confidence that NAA will meet its schedule and performance commitments.”9

Phillips and his task force returned to Downey for a follow-up week in mid-April 1966. He did not amend the original conclusions; but he told President Atwood that North American was moving in the right direction.10

The astronauts themselves suggested many changes in the block I spacecraft design. In April 1967, Donald K. Slayton was to tell the Subcommittee on NASA Oversight of the House Committee on Science and Astronautics that the astronauts had recommended 45 improvements, including a new hatch. North American had acted on 39 of these recommendations. They were introducing the other six into later spacecraft. “Most of these,” Slayton testified, “were of a relatively minor nature.”11 The only major change for later spacecraft was to have been a new hatch. And the astronauts had recommended this not so much for safety as for ease in getting out for space-walks and at the end of flights.12

The Spacecraft Comes to KSC

In July and August 1966, NASA officials conducted a customer acceptance readiness review at North American Aviation’s Downey plant, issued a certificate of worthiness, and authorized spacecraft 012 to be shipped to the Kennedy Space Center. The certificate listed incomplete work: North American Aviation had not finished 113 significant engineering orders at the time of delivery.13

The command module arrived at KSC on 26 August and went to the pyrotechnic installation building for a weight and balance demonstration.14 With the completion of the thrust vector alignment on 29 August, the test team moved the command module to the altitude chamber in the operations and checkout building and began mating the command and service modules. Minor problems with the service module had already showed up, and considerable difficulties with the new mating hardware caused delays.

On 7 September NASA released a checkout schedule. By 14 September, while the Saturn launch vehicle moved on schedule, the Apollo spacecraft already lagged four days behind. On the same day, a combined systems test was begun. Discrepancy reports numbered 80 on 16 September and had risen to 152 within six days. One of the major problems was a short in the radio command system. In the meantime, the test team had installed all but one of the flight panels. At Headquarters during this time, a board chaired by the Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight, Dr. George Mueller, and made up of OMSF center directors, conducted a detailed review of the spacecraft. On 7 October this board certified the design as “flightworthy, pending satisfactory resolution of listed open items.”15

The simulated altitude run, originally scheduled for 26 September, had gradually slipped back in schedule. It was run on 11 October, but plans for an unmanned altitude run on 12 October, a flight crew altitude run on 14 October, and a backup crew run on 15 October also slipped. So did the projected dates of mechanical mating of the spacecraft with the launch vehicle and the launch itself.

The unmanned altitude chamber run finished satisfactorily on 15 October. The first manned run in the altitude test chamber, on 18 October, experienced trouble after reaching a simulated altitude of 4,000 meters because of the failure of a transistor in one of the inverters. With the replacement of the inverter, the system functioned satisfactorily. The prime crew of Grissom, White, and Chaffee repeated the 16-hour run the next day with only one major problem developing in the oxygen cabin supply regulator. This problem caused a delay of the second manned run with the backup crew scheduled for 21 October. Continued trouble with the new oxygen regulator caused the indefinite suspension of the second manned test before the end of October. By this time it had become clear that the spacecraft needed a new environmental control unit. Technicians removed the old unit on 1 November.

Meanwhile, at North American Aviation’s Downey plant a propellant tank had ruptured in the service module of spacecraft 017. This provoked a special test of the propellant tanks on the 012 service module at KSC. In order to conduct this testing in parallel with further checking of the command module, the test team removed the command module from the altitude chamber.16 Later they removed the fuel tanks from the service module in the chamber. After pressure-integrity tests, they replaced the tanks and returned the command module to the chamber.17 The test team installed and fit checked the new environmental control unit on 8 November and hooked up the interface lines two days later. But this did not completely solve the difficulties. Problems in the glycol cooling system surfaced toward the end of November and on 5 December forced a removal of the second environmental control unit.

The Apollo Review Board was to say of this glycol leakage several months later,

water/glycol coming into contact with electrical connectors can cause corrosion of these connectors. Dried water/glycol on wiring insulation leaves a residue which is electrically conductive and combustible. Of the six recorded instances where water/glycol spillage or leakage occurred (a total of 90 ounces leaked or spilled is noted in the records) the records indicate that this resulted in wetting of conductors and wiring on only one occasion. There is no evidence which indicates that damage resulted to the conductors or that faults were produced on connectors due to water/glycol.18

The difficulties in the materials that already had arrived at KSC and the endless changes that came in from North American Aviation - 623 distinct engineering orders - presented major problems for the NASA-NAA test teams. As many workmen as could possibly function inside the command module continually swarmed into it to replace defective equipment or make the changes that NAA suggested and Houston approved. The astronauts came and went, sometimes concerned with major and sometimes with minor matters on the spacecraft.19

These difficulties at KSC and concurrent problems at Mission Control Center, Houston, forced two revisions to the schedule, one on 17 November, the next on 9 December. The test team kept up with or moved ahead of the latter schedule during the ensuing weeks. The third environmental control unit arrived for installation on 16 December.

The test teams had been working on a 24-hour basis since the arrival of the spacecraft at Kennedy, taking off only on Christmas and New Year’s Day. On 28 December, while conducting an unmanned altitude run, the test team located a radio frequency communications problem and referred it to ground support technicians for correction. On 30 December a new backup crew of Schirra, Eisele, and Cunningham (McDivitt’s original backup crew had received a new assignment) successfully completed a manned altitude run.20 Six major problems on the spacecraft surfaced, one in very-high-frequency radio communications; but a review board was to give a favorable appraisal not long afterward: “This final manned test in the altitude chamber was very successful with all spacecraft systems functioning normally. At the post-test debriefing the backup flight crew expressed their satisfaction with the condition and performance of the spacecraft.”21

By 5 January the mating of the spacecraft to the lunar module adapter and the ordnance installation were proceeding six days ahead of schedule. The following day the spacecraft was moved from the operations and checkout building to LC-34. KSC advanced the electrical mating and the emergency detection system tests to 18 January, and these were completed that day. The daily status report for 20 January 1967 reported that no significant problems occurred during the plugs-in overall test. A repeat of the test on 25 January took 24 hours. A problem in the automatic checkout equipment link-up caused the delay. Further, the instrument unit did not record simulated liftoff - a duplication of an earlier deficiency. The schedule called for a plugs-out test at 3:00 p.m. on 26 January, a test in which the vehicle would rely on internal power. NASA did not rate the plugs-out test as “hazardous,” reserving that label for tests involving fueled vehicles, hypergolic propellants, cryogenic systems, high-pressure tanks, live pyrotechnics, or altitude chamber tests.22

The Hunches of Tom Baron

All the tests and modifications in the spacecraft did not go far enough or fast enough in the view of one North American employee, Thomas R. Baron of Mims, Florida. Baron’s story has significance for two reasons. His attitude reflected the unidentified worries of many who did not express them until too late. Also, the reaction of KSC managers indicated a determination to check every lead that might uncover an unsafe condition. The local press at the time gave ample but one-sided coverage of the Baron story.

Baron had a premonition of disaster. He believed his company would not respond to his warnings and wanted to get his message to the top command at KSC. While a patient at Jeff Parrish Hospital in Titusville, Florida, during December 1966, and later at Holiday Hospital in Orlando, Baron expressed his fears to a number of people. His roommate at Jeff Parrish happened to be a KSC technical writer, Michael Mogilevsky.23 After Baron claimed to have in his possession documentary evidence of deficiencies in the heat shield, cabling, and life support systems, Mogilevsky went to see Frank Childers in NASA Quality Control on 16 December. Childers called in an engineer of the Office of the Director of Quality Assurance, and Mogilevsky related Baron’s complaints and fears again.24

That evening Rocco Petrone asked John M. Brooks, the Chief of NASA’s Regional Inspections Office, to locate and interview Baron. Brooks interviewed Baron twice and briefed Debus, Albert Siepert, and Petrone on Baron’s complaints: poor workmanship, failure to maintain cleanliness, faulty installation of equipment, improper testing, unauthorized deviations from specifications and instructions, disregard for rules and regulations, lack of communication between Quality Control and engineering organizations and personnel, and poor personnel practices.

Baron claimed to possess notebooks that would substantiate his charges. He promised to cooperate with KSC and with North American Aviation if someone above his immediate supervisor would listen to what he had to say. He did not believe his previous complaints had ever gone beyond that supervisor. He asked to be allowed to talk to John Hansel, Chief of Quality Control for North American. Baron’s complaints were against North American, not KSC. He believed that the center needed additional personnel to enforce compliance with procedures in the Apollo program. Brooks later reported: “Baron was assured that an appropriate level of NAA management would be in touch with him in the next day or two.”25

On 22 December 1966, Petrone and Wiley E. Williams, Test and Operations Management Office, Directorate for Spacecraft Operations, received a briefing on Baron’s complaints. The two men recognized that these were primarily North American Aviation in-house problems and that the company should inquire into Baron’s complaints and advise KSC officials of the results. NAA officials W. S. Ford, James L. Pearce, and John L. Hansel met with Petrone that same day. They arranged to talk with Baron the following day.26

Since Baron had confidence in Hansel, who was an expert in Quality Control, Hansel’s testimony is especially valuable. Baron had lots of complaints but, Hansel insisted, no real proof of major deficiencies, either in the papers Baron had in his possession or in the report that Baron wrote (and Hansel was to read) a short time later. Lastly, Hansel stated, Baron was not working in a critical area at that time.27

North American informed Petrone of the interview by 4 January, but sent no written report to Petrone’s office.28 On 5 January a North American spokesman told newsmen that the company was terminating Baron’s services.29 Since his clearance at the space center had been withdrawn, Baron phoned John Brooks, the NASA inspector, on 24 January and invited him to his home. Brooks accepted the invitation, and Baron gave him a 57-page report for duplication and use. Brooks duplicated it and returned the original to Baron on 25 January.30 Brooks assured Baron that KSC and NAA had looked into his allegations and taken corrective action where necessary.

Petrone received a mimeographed copy of Baron’s report on 26 January. John Wasik of the Titusville Star Advocate telephoned Brooks to ask about KSC’s interest in Baron’s information. Wasik indicated that he was going to seek an interview with Petrone. On the following morning, Gordon Harris, head of the Public Affairs Office at KSC, heard that Wasik had spent approximately one and one-half hours with Zack Strickland, of the North American Aviation Public Relations Information Office, going over the Baron report.31

That same day Hansel, North American’s head of Quality Control - the man Baron had hoped his report would reach - told Wasik that Baron was one of the most conscientious quality control men he ever had working for him and that his work was always good. “If anything,” Hansel related in the presence of Strickland, “Baron was too much of a perfectionist. He couldn’t bend and allow deviations from test procedures - and anyone knows that when you’re working in a field like this, there is constant change and improvement. The test procedures written in an office often don’t fit when they are actually applied. Baron couldn’t understand this.” Wasik also stated: “Hansel readily agreed that Baron’s alleged discrepancies were, for the most part, true.”32 What Wasik did not say was that none of the discrepancies, true though they were, was serious enough to cause a disaster.

Hansel was not alone in his misgivings about Baron. Hansel did not know of Frank Childers’s report nor had he ever talked to Childers about Baron. Childers, too, had doubts about the man’s reliability. Even though he had sympathetically reported to NASA officials the fears of the North American employee, Childers admitted that Baron, who signed himself T. R. Baron, had the nickname “D. R. (Discrepancy Report) Baron.”33 R. E. Reyes, an engineer in KSC’s Preflight Operations Branch, said Baron filed so many negative charges that, had KSC heeded them all, NASA would not have had a man on the moon until the year 2069.34 To confirm the opinions of these men, Baron himself admitted before a congressional investigating committee a short time later that he had turned in so many negative reports that his department ran out of the proper forms. Further - in confirmation of Hansel’s view of Baron’s report - Baron based his testimony on hearsay, not on any personal records in his possession.35 Baron’s forebodings were to prove correct, but not for any reason he could document.*

Both NASA and North American Aviation, a historian must conclude, gave far more serious consideration to Baron’s complaints than a casual perusal of newspapers during the succeeding weeks, or even close reading of such books as Mission to the Moon, would indicate.36

- The Chairman of the House Subcommittee on NASA Oversight, Congressman Olin Teague of Texas, said in thanking Baron for his testimony: “What you have done has caused North American to search their procedures.” House Subcommittee on NASA Oversight, Investigation into Apollo 204 Accident, 1: 499.

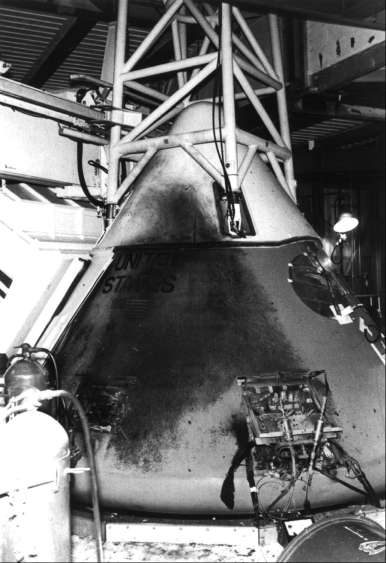

Disaster at Pad 34

While top administrators were checking out the fears of Tom Baron, two NASA men, Clarence Chauvin and R. E. Reyes, and two North American Project Engineers, Bruce Haight and Chuck Hannon, met on the morning of 26 January at launch complex 34 to review the general spacecraft readiness and configuration for one of the last major previews, the plugs-out test. The craft looked ready.37

That same night the prime and backup crews studied mission plans. The next day a simulated countdown would start shortly before liftoff and then the test would carry through several hours of flight time. There would be no fuel in the Saturn. Grissom, White, and Chaffee would don their full spacesuits and enter the Apollo, breathing pure oxygen to approximate orbital conditions as closely as possible. After simulated liftoff, the spacecraft center in Houston would monitor the performance of the astronauts. The plugs-out test did not rate a hazardous classification; the spacecraft had successfully operated in the test chamber for a greater period of time than it would on the pad.38

The astronauts entered the Apollo at 1:00 p.m., Friday, 27 January 1967. Problems immediately arose. NASA Spacecraft Test Conductor Clarence Chauvin later described them: “The first problem that we encountered was when Gus Grissom ingressed into the spacecraft and hooked up to his oxygen supply from the spacecraft. Essentially, his first words were that there was a strange odor in the suit loop. He described it as a ’sour smell’ somewhat like buttermilk.” The crew stopped to take a sample of the suit loop, and after discussion with Grissom decided to continue the test.

The next problem was a high oxygen flow indication which periodically triggered the master alarm. The men discussed this matter with environmental control systems personnel, who believed the high flow resulted from movements of the crew. The matter was not really resolved.

A third serious problem arose in communications. At first, faulty communications seemed to exist solely between Command Pilot Grissom and the control room. The crew made adjustments. Later, the difficulty extended to include communications between the operations and checkout building and the blockhouse at complex 34. “The overall communications problem was so bad at times,” Chauvin testified, “that we could not even understand what the crew was saying.”39 William H. Schick, Assistant Test Supervisor in the blockhouse at complex 34, reported in at 4:30 p.m. and monitored the spacecraft checkout procedure for the Deputy of Launch Operations. He sat at the test supervisor’s console and logged the events, including various problems in communications.40 To complicate matters further, no one person controlled the trouble-shooting of the communications problem.41 This failure in communication forced a hold of the countdown at 5:40 p.m. By 6:31 the test conductors were about ready to pick up the count when ground instruments showed an unexplained rise in the oxygen flow into the spacesuits. One of the crew, presumably Grissom, moved slightly.

Four seconds later, an astronaut, probably Chaffee, announced almost casually over the intercom: “Fire. I smell fire.” Two seconds later, Astronaut White’s voice was more insistent: “Fire in the cockpit.”

In the blockhouse, engineers and technicians looked up from their consoles to the television monitors trained at the spacecraft. To their horror, they saw flames licking furiously inside Apollo, and smoke blurred their pictures. Men who had gone through Mercury and Gemini tests and launches without a major hitch stood momentarily stunned at the turn of events. Their eyes saw what was happening, but their minds refused to believe. Finally a near hysterical shout filled the air: “There’s a fire in the spacecraft!”

Procedures for emergency escape called for a minimum of 90 seconds. But in practice the crew had never accomplished the routines in the minimum time. Grissom had to lower White’s headrest so White could reach above and behind his left shoulder to actuate a ratchet-type device that would release the first of a series of latches. According to one source, White had actually made part of a full turn with the ratchet before he was overcome by smoke. In the meantime, Chaffee had carried out his duties by switching the power and then turning up the cabin lights as an aid to vision. Outside the white room that totally surrounded the spacecraft, Donald O. Babbitt of North American Aviation ordered emergency procedures to rescue the astronauts. Technicians started toward the white room. Then the command module ruptured.42

Witnesses differed as to how fast everything happened. Gary W. Propst, an RCA technician at the communication control racks in area D on the first floor at launch complex 34, testified four days later that three minutes elapsed between the first shout of “Fire” and the filling of the white room with smoke. Other observers had gathered around his monitor and discussed why the astronauts did not blow the hatch and why no one entered the white room. One of these men, A. R. Caswell, testified on 2 February, two days after Propst. In answer to a question about the time between the first sign of fire and activity outside the spacecraft in the white room, he said: “It appeared to be quite a long period of time, perhaps three or four minutes. . . .”43

The men on the launch tower told a different story. Bruce W. Davis, a systems technician with North American Aviation who was on level A8 of the service structure at the time of the fire, reported an almost instantaneous spread of the fire from the moment of first warning. “I heard someone say, ‘There is a fire in the cockpit.’ I turned around and after about one second I saw flames within the two open access panels in the command module near the umbilical.” Jessie L. Owens, North American Systems Engineer, stood near the pad leader’s desk when someone shouted: “Fire.” He heard what sounded like the cabin relief valve opening and high velocity gas escaping. “Immediately this gas burst into flames somewhat like lighting an acetylene torch,” he said. “I turned to go to the white room at the above-noted instant, but was met by a flame wall.”44

Spacecraft technicians ran toward the sealed Apollo, but before they could reach it, the command module ruptured. Flame and thick black clouds of smoke billowed out, filling the room. Now a new danger arose. Many feared that the fire might set off the launch escape system atop Apollo. This, in turn, could ignite the entire service structure. Instinct told the men to get out while they could. Many did so, but others tried to rescue the astronauts.

Approximately 90 seconds after the first report of fire, pad leader Donald Babbitt reported over a headset from the swing arm that his men had begun attempts to open the hatch. Thus the panel that investigated the fire concluded that only one minute elapsed between the first warning of the fire and the rescue attempt. Babbitt’s personal recollection of his reporting over the headset did not make it clear that he had already been in the white room, as the panel seemed to conclude.45 Be that as it may, for more than five minutes, Babbitt and his North American Aviation crew of James D. Gleaves, Jerry W. Hawkins, Steven B. Clemmons, and L. D. Reece, and NASA’s Henry H. Rodgers, Jr., struggled to open the hatch. The intense heat and dense smoke drove one after another back, but finally they succeeded. Unfortunately, it was too late. The astronauts were dead. Firemen arrived within three minutes of the hatch opening, doctors soon thereafter. A medical board was to determine that the astronauts died of carbon monoxide asphyxia, with thermal burns as contributing causes. The board could not say how much of the burns came after the three had died. Fire had destroyed 70% of Grissom’s spacesuit, 25% of White’s, and 15% of Chaffee’s.46 Doctors treated 27 men for smoke inhalation. Two were hospitalized.

Rumors of disaster spread in driblets through the area. Men who had worked on the day shift returned to see if they could be of help. Crewmen removed the three charred bodies well after midnight.47

The sudden deaths of the three astronauts caused international grief and widespread questioning of the space program. Momentarily the whole manned lunar program stood in suspense. Writing in Newsweek, Walter Lippman immediately deplored what he called the pride-spurred rush of the program.48 The Washington Sunday Star spoke of soaring costs and claimed that “know-who” had more to do than “know-how” in the choice of North American over Martin Marietta as prime contractor for the spacecraft.49 A long-time critic of the space program, Senator William J. Fulbright of Arkansas, Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, placed the “root cause of the tragedy” in “the inflexible, but meaningless, goal of putting an American on the moon by 1970” and called for a “full reappraisal of the space program.” The distinguished scientist Dr. James A. Van Allen, discoverer of radiation belts in space, charged that NASA was “losing its soul.” It had become “a huge engineering, technological and operational agency with less and less devotion to the true spirit of exploration and to the advancement of basic knowledge.”50 A lead editorial in the New York Times spoke of the incompetence and negligence that became apparent as the full story of disaster came to light, but put the central blame on “the technically senseless” and “highly dangerous” dedication to the meaningless timetable of putting a man on the moon by 1970.51 An article in the American Institute of Chemical Engineers Journal had the long-anticipated title: “NASA’s in the Cold, Cold Ground.”52 But President Johnson held firm to the predetermined goal and communicated his confidence to NASA.53

The Review Board

After removal of the bodies, NASA impounded everything at launch complex 34. On 3 February, NASA Administrator Webb set up a review board to investigate the matter thoroughly. Except for one Air Force officer and an explosives expert from the Bureau of Mines, both specialists in safety, all the members of the board came from NASA.* North American Aviation had a man on the board for one day. At least George Jeffs, NAA’s chief Apollo engineer, thought he was on the board. After consultation with Shea and Gilruth of the Manned Space Flight Center, North American officials recommended him as one who could contribute more than any other NAA officer. Jeffs flew to the Cape and sat in on several meetings until, as Jeffs was to report later to the House Subcommittee on NASA Oversight, “I was told that I was no longer a member of the Board.” The representative of the review board who dismissed Jeffs gave no reason for the dismissal.54 Thus all members of the board were government employees, a fact that was to cause NASA considerable criticism from Congress.

Debus asked all KSC and contractor employees for complete cooperation with the review board. He called their attention to the Apollo Mission Failure Contingency Plan of 13 May 1966 that prohibited all government and contractor employees from discussing technical aspects of the accident with anyone other than a member of the board. All press information would go through the Public Affairs Office. In scheduled public addresses, speakers might discuss other aspects of the space program but “should courteously but absolutely refuse to speculate at this time on anything connected with the Apollo 204 investigation or with factors that might be related, directly or indirectly, to the accident.”55 Debus’s action muted at KSC the wild rumors that had prevailed in east Florida and spread throughout the country after the fire.56

Under authorization from the review board, ground crews carefully removed the debris on the crew couches inside the command module on 3 February. They recorded the type and location of the material removed. Then they laid a plywood shelf across the three interlocked seats so that combustion specialists could enter the command module and examine the cabin more thoroughly. On the following day they removed the plywood and the three seats. Two days after that, they suspended a plastic false floor inside the command module so that investigators could continue to examine the command module interior without aggravating the condition of the lower part of the cabin.57

Engineers at the Manned Spacecraft Center duplicated conditions of Apollo 204 without crewmen in the capsule. They reconstructed events as studies at KSC brought them to light. The investigation on pad 34 showed that the fire started in or near one of the wire bundles to the left and just in front of Grissom’s seat on the left side of the cabin - a spot visible to Chaffee. The fire was probably invisible for about five or six seconds until Chaffee sounded the alarm. “From then on,” a Time writer stated, “the pattern and the intensity of the test fire followed, almost to a second, the pattern and intensity of the fire aboard Apollo 204.”58

The members of the review board sifted every ash in the command module, photographed every angle, checked every wire, and questioned in exhausting detail almost everyone who had the remotest knowledge of events related to the fire. They carefully dismantled and inspected every component in the cockpit.59

In submitting its formal report to Administrator Webb on 5 April 1967, the board summarized its findings: “The fire in Apollo 204 was most probably brought about by some minor malfunction or failure of equipment or wire insulation. This failure, which most likely will never be positively identified, initiated a sequence of events that culminated in the conflagration.”** 60

To the KSC Safety Office, the next finding of the Review Board seemed to be the key to the entire report: “Those organizations responsible for the planning, conduct and safety of this test failed to identify it as being hazardous.”61 Since NASA had not considered the test hazardous, KSC had not instituted those procedures that normally would have accompanied such a test.62

The Review Board had other severe criticism:

Deficiencies existed in Command Module design, workmanship and quality control. . . .

The Command Module contained many types and classes of combustible material in areas contiguous to possible ignition sources. . . . The rapid spread of fire caused an increase in pressure and temperature which resulted in rupture of the Command Module and creation of a toxic atmosphere. . . . Due to internal pressure, the Command Module inner hatch could not be opened prior to rupture of Command Module. . . . The overall communications system was unsatisfactory. . . . Problems of program management and relationships between Centers and with the contractor have led in some cases to insufficient response to changing program requirements. . . . Emergency fire, rescue and medical teams were not in attendance. . . . The Command Module Environmental Control System design provides a pure oxygen atmosphere. . . . This atmosphere presents severe fire hazards.63

A last recommendation went beyond hazards: “Every effort must be made to insure the maximum clarification and understanding of the responsibilities of all the organizations involved, the objective being a fully coordinated and efficient program.”64

The review board recommended that NASA continue its program and get to the moon and back before the end of 1969. Safety, however, was to be a prime consideration, outranking the target date. The board urged, finally, that NASA keep the appropriate congressional committees informed on significant problems arising in its programs.

Astronaut Frank Borman, a member of the board, summed up the fact that everyone had taken safety in ground testing for granted. The crewmen, he stated, had the right not to enter the spacecraft if they thought it was unsafe. However, “none of us,” Borman insisted, “gave any serious consideration to a fire in the spacecraft.”65

The board members sharply criticized the fact that the astronauts had no quick means of escape and recommended a redesigned hatch that could be opened in two to three seconds instead of a minute and a half. They proposed a number of other changes in the design of both the spacecraft and the pad and recommended revised practices and procedures for emergencies. Many of these, incidentally, KSC already had in its plans for “hazardous” operations.66

One of the most amazing facts to come out in the testimony of so many at KSC was the complicated process of communications. A contractor employee would confer with his NASA counterpart, who would in turn get in touch with his supervisor, who would in turn report to someone else in the chain of command. It must have seemed to the review board easier for a man on the pad to get through to the White House than to reach a local authority in time of an emergency.67

- The NASA members were: the chairman, Dr. Floyd L. Thompson, Dir., Langley Research Center; Astronaut Frank Borman, Manned Spacecraft Center; Dr. Maxime A. Faget, Dir., Engineering and Development, MSC; E. Barton Geer, Assoc. Chief, Flight Vehicles and Systems Div., Langley; George C. White, Jr., Dir. of Reliability and Quality, Apollo Program Off.; and John J. Williams, Dir., Spacecraft Operations, Kennedy. The non-NASA members were Dr. Robert W. Van Dolah, Research Dir., Explosive Research Center, Bureau of Mines, Dept. of the Interior; and Col. Charles F. Strange, Chief of Missiles and Space Safety Div., Off. of the Air Force Inspector General, Norton AFB, CA. Report of Apollo 204 Review Board, p. 5. The only non-government person on the original board, Dr. Frank Long of Cornell Univ., a member of the President’s Scientific Advisory Committee, soon resigned because of the press of other activities and was replaced by Van Dolah. Aviation Week and Space Technology, 13 Feb. 1967, p. 33.

- The review board ignored and a congressional committee later vehemently rejected the hypothesis of Dr. John McCarthy, NAA Division Director of Research, Engineering, and Test, that Grissom accidentally scuffed the insulation of a wire in moving about the spacecraft. (Investigation into Apollo 204 Accident, 1 : 202, 263.) In the same congressional investigation, Col. Frank Borman, the first astronaut to enter the burnt-out spacecraft, testified: “We found no evidence to support the thesis that Gus, or any of the crew members kicked the wire that ignited the flammables.” This theory that a scuffed wire caused the spark that led to the fire still has wide currency at Kennedy Space Center. Men differ, however, on the cause of the scuff.

Congress Investigates

When the review board began its investigation in February, the Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences held a few hearings but confined its queries to major NASA officials.68 When the Apollo 204 Review Board turned in its report to Administrator Webb, the Senate Committee enlarged the scope of its survey; and the House Committee on Science and Astronautics, more particularly the Subcommittee on NASA Oversight, went into action.

Congress had wider concerns, however, than the mechanics of the fire that had occupied so much of the review board’s time. Both houses, and especially two legislators from Illinois, freshman Senator Charles Percy and Representative Donald Rumsfeld, showed great interest in the composition of the review board, especially its lack of non-government investigators.69 Members of Congress questioned the board’s omission of any analysis of the possibility of weakness in the managerial structure that might have allowed conditions to approach the point of disaster. Senator Edward Brooke of Massachusetts wondered about the extensive involvement of North American Aviation and its capacity to handle such a huge percentage of the Apollo contracts.70 To the surprise of both NASA and NAA officials, members of both the Senate and House committees were to take a growing interest in the report of the Phillips review team of December 1965. This probing was to lead to some embarrassing moments for Mueller of NASA and Atwood of North American Aviation.71 But these aspects of the hearings belong more properly to the NASA Headquarters history.

Questioning of Debus by two members of the House Committee on Science and Astronautics at a hearing in Washington on the evening of 12 April bears directly on the KSC story. Congressman John Wydler of New York asked Debus to clarify his secrecy directive, which Wydler believed had caused some misunderstanding. Debus read his initial directive of 3 February, which asked for total cooperation with the board and squelched other discussion of the disaster; and then his second announcement of 11 April, after the review board had submitted its report, which removed all restraints.72 Wydler seemed satisfied.

When Congressman James Fulton of Pennsylvania asked Debus a few minutes later if he would like to make a short statement for the record, Debus came out candidly:

As director of the installation I share the responsibility for this tragic accident and I have given it much thought. It is for me very difficult to find out why we did not think deeply enough or were not inventive enough to identify this as a very hazardous test.

I have searched in my past for safety criteria that we developed in the early days of guided missile work and I must say that there are some that are subject to intuitive thinking and forward assessment. Some are made by practical experience and involved not only astronauts but the hundreds of people on the pads. . . .

It is very deplorable but it was the known condition which started from Commander Shepard’s flight. . . . from then on we developed a tradition that. . . . considered the possibility of a fire but we had no concept of the possible viciousness of this fire and its speed.

We never knew that the conflagration would go that fast through the spacecraft so that no rescue would essentially help. This was not known. This is the essential cause of the tragedy. Had we known, we would have prepared with as adequate support as humanly possible for egress.73

Congressman Fulton congratulated Debus on his statement. “This is why we have confidence in NASA. We have been with you on many successes. We have been with you on previous failures, not so tragic. . . . The Air Force had five consecutive failures and this committee still backed them and said go ahead.” By looking at matters openly and seeking better procedures, Fulton felt that NASA was making progress.74

The House Subcommittee on NASA Oversight, under the chairmanship of Olin Teague of Texas, held hearings at the Kennedy Space Center on 21 April. When the investigation opened, it soon became clear - as the review board had already learned - that any emergency procedures at the space center would be extremely complicated matters involving conferences between NASA and contractor counterparts, and even in certain instances with representatives of the Air Force safety section. Beyond this the most noteworthy event of the hearing was the recommendation of Congressman Daddario that the members commend the brave men on the pad* who had tried to save the astronauts.75

While the Senate committee in Washington spent a great deal of time on the Phillips report, and embarrassed NASA and NAA officials with questions about the document, the committee finally had to agree with the testimony that “the findings of the Phillips task force had no effect on the accident, did not lead to the accident, and were not related to the accident.”76 On the positive side, the committee learned from President Atwood that North American Aviation had made substantial changes in its management. The firm had placed William B. Bergen, former president of Martin-Marietta, in charge of its Space Division; obtained the full-time services of Bastian Hello and hired as consultant G. T. Wiley, both former Martin officials; and transferred one of its own officers, P. R. Vogt, from the Rocketdyne Division to the Space Division. Atwood testified that North American would probably make other changes.77 In the end, the Senate committee recommended that NASA move forward to achieve its goal within the prescribed time, but reaffirmed the review board’s insistence that safety take precedence over target dates, and reminded NASA to keep appropriate congressional committees informed of any significant problems that might arise in its program.78

- Six spacecraft technicians who had risked their lives to save the astronauts received the National Medal for Exceptional Bravery on 24 October 1967. They were Henry H. Rodgers, Jr., of NASA, and Donald O. Babbitt, James D. Gleaves, Jerry W. Hawkins, Steven B. Clemmons, and L. D. Reece, all of North American Aviation. Taylor, Liftoff, p. 267.

Reaction at KSC

During the ensuing months, NASA took many steps to prevent future disasters. It gave top priority to a redesigned hatch, a single-hinged door that swung outward with only one-half pound of force. An astronaut could unlatch the door in three seconds. The hatch had a push-pull unlatching handle, a window for visibility in flight, a plunger handle inside the command module to unlatch a segment of the protective cover, a pull loop that permitted someone outside to unlatch the protective cover, and a counterbalance that would hold the door open.79 NASA revised flight schedules. An unmanned Saturn V would go up in late 1967, but the manned flight of the backup crew for the Grissom team - Schirra, Eisele, and Cunningham - would not be ready before the following May or June.80 In the choice of materials for space suits, NASA settled on a new flame-proof material called “Beta Cloth” instead of nylon. Within the spacecraft, technicians covered exposed wires and plumbing to preclude inadvertent contact, redesigned wire bundles and harness routings, and increased fire protection.

Initially, NASA administrators said they would stay with oxygen as the atmosphere in the spacecraft. But after a year and a half of testing, NASA was to settle on a formula of 60% oxygen and 40% nitrogen. NASA provided a spacecraft mockup at KSC for training the rescue and the operational teams. At complex 34 technicians put a fan in the white room to ventilate any possible smoke. They added water hoses and fire extinguishers and an escape slide wire. Astronauts and workers could ride down this wire during emergencies, reaching the ground from a height of over 60 meters in seconds.81

NASA safety officers were instructed to report directly to the center director. At Kennedy this procedure had been the practice for some time. A Headquarters decision also extended the responsibilities of the Flight Safety Office at Kennedy. Test conductors and all others intimately involved with the development of the spacecraft and its performance sent every change in procedure to the Flight Safety Office for approval.82

The fire had a significant impact on KSC’s relations with the spacecraft contractors. When KSC had absorbed Houston’s Florida Operations team in December 1964, the launch center was supposed to have assumed direction of the spacecraft contractors at the Cape. The North American and Grumman teams at KSC, however, had continued to look to their home offices, and indirectly to Houston, for guidance. This ended in the aftermath of LC-34’s tragedy. With the support of NASA Headquarters, KSC took firm control of all spacecraft activities at the launch center.

The Boeing-TIE Contract

To strengthen program management further, NASA entered into a contract with the Boeing Company to assist and support the NASA Apollo organization in the performance of specific technical integration and evaluation functions. NASA retained responsibility for final technical decisions.83 This Boeing-TIE contract, as it came to be called at KSC, proved the most controversial of all post-fire precautions. Many in middle or lower echelons at KSC criticized it. They looked upon it as a public relations scheme to convince Congress of NASA’s sincere effort to promote safety.

Even NASA Headquarters found it difficult to explain to a congressional subcommittee either the expenditure of $73 million in one year on the contract, or that it had hired a firm to inspect work which that firm itself performed. As a matter of fact one segment of the Boeing firm - that working under the TIE contract - had to check on another, the one that worked on the first stage of Saturn V. Mueller explained to the committee that “the Boeing selection for the TIE contract. . . . was based upon the fact that this was an extension of the work [Boeing personnel] were already doing in terms of integrating the Saturn V launch vehicle.”84

When a member of the committee staff called Mueller’s attention to the fact that Boeing had problems with its own specific share of the total effort, Mueller’s defense of the contract rested on the old adage that “nothing succeeds like success.” He felt that if the total program succeeded, the nation would no longer question specific aspects and expenditures.85

Boeing sent 771 people to KSC, one-sixth of the total it brought onto NASA installations under the TIE contract. In such a speedy expansion, the quality of performance was spotty. The “TIE-ers” were to find it difficult to get data from other contractors, as well as from NASA personnel. The men at KSC felt they had the personnel to do themselves what the TIE-ers were attempting to do.

The TIE statement of work at KSC carried a technical description of twelve distinct task areas: program integration, engineering evaluation, program control, interface and configuration management, safety, test, design certification reviews, flight readiness reviews, logistics, mission analysis, Apollo Space System Engineering Team, and program assurance.86

Many KSC personnel felt that the TIE contract was too much like the General Electric contract they had fought a few years before. In this they forgot that the earlier contract had been a permanent one, which would have given GE access to its competitors’ files, and thus involved a conflict of interest. The Boeing-TIE contract had a specific purpose and a time limit. NASA made the arrangement on an annual basis. Further, those who criticized the number of Boeing personnel forgot that one could not assess the size of the problem until he investigated it.

The TIE personnel located and defined delays in the progress of equipment to the Kennedy Space Center. They spotted deficiencies in equipment. They discovered erroneous color coding of lines, for instance, that might have caused a disaster. The insulation of pipes had obscured the color and men had improperly tagged the sources of propellants and gases. When tests at KSC proved changes of equipment necessary, the TIE personnel expedited these changes. They set down time schedules for necessary adjustments. They eliminated extraneous material from the interface control documents. But it remains difficult to assess the exact contribution of the TIE contract.87

Far more important than the efforts of the 771 Boeing-TIE personnel, or any specific recommendation of the review board (except perhaps that calling for a new hatch design), the most significant difference at Kennedy Space Center was a larger awareness of how easily things could go wrong. For a long time no test or launch would be thought of as a foregone success.

Most important of all, in spite of the disaster, the President, the Congress, the nation, and NASA itself determined that the moon landing program would go on with the hope of coming as close to President Kennedy’s target date as possible.

ENDNOTES

- Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, Report on Apollo 204 Accident, report 956, 90th Cong., 2nd sess., 30 Jan. 1968, pp. 3-7.X

- Idem, Apollo Accident: Hearings, 90th Cong., 1st sess., pt. 1, pp. 13-54. Dr. Charles A. Berry, chief of medical programs at MSC, introduced and discussed Dr. E. Roth’s four-part report, “The Selection of Space- Cabin Atmosphere."X

- Frank J. Handel, “Gaseous Environments during Space Missions," Journal of Space Craft and Rockets 1 (July-Aug. 1964): 361.X

- Report of Apollo 204 Review Board to the Administrator, NASA, 5 Apr. 1967, app. D, panel 2, pp. D-2- 25, D-2-26.X

- Science Journal 2 (Feb. 1966): 83.X

- Space/Aeronautics 45 (Feb. 1966): 26, 28, 32.X

- Gen. Samuel Phillips, Apollo Program Dir., to John Leland Atwood, Pres., North American Aviation, “NASA Review Team Report," 19 Dec. 1965.X

- Ibid., p. 1.X

- Ibid., p. 66.X

- Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, Report on Apollo 204 Accident, pt. 4, p. 318.X

- House Subcommittee on NASA Oversight of the Committee on Science and Astronautics, Investigation into Apollo 204 Accident: Hearings, 90th Cong., 1st sess., 1: 404.X

- Ibid., p. 450.X

- Report of Apollo 204 Review Board, p. 4-1.X

- "Daily Status Report, AS-204," 29 Aug. 1966; unless otherwise noted, the material in this section is based on these reports between 29 Aug. 1966 and 26 Jan. 1967.X

- Report of Apollo 204 Review Board, p. 4-1.X

- Ibid., pp. 4-1, 4-2.X

- Chauvin interview, 6 June 1974.X

- Report of Apollo 204 Review Board, p. 4-2.X

- Chauvin and Reyes interviews, 6-7 June 1974.X

- Ibid.X

- Report of Apollo 204 Review Board, p. 4-2.X

- Ibid.X

- Notes by M. Mogilevsky, signed, undated, relative to his conversation with Thomas R. Baron, 12-13 Dec. 1966, in files of Frank Childers, KSC.X

- Statement of Frank Childers, 9 Feb. 1967, submitted at the request of the KSC Director, copy in files of Childers.X

- John H. Brooks, Chief, NASA Regional Inspections Off., to Kurt Debus, “Thomas Ronald Baron, North American Aviation Employee," 3 Feb. 1967.X

- Ibid.X

- Hansel interview.X

- Brooks to Debus, 3 Feb. 1967.X

- Orlando Sentinel, 6 Feb. 1967. John Hansel said later than North American had ample reason for firing Baron, because he had violated procedural requirements that brought automatic dismissal. Hansel interview.X

- Brooks to Debus, 3 Feb. 1967.X

- Ibid.X

- Titusville Star-Advocate, 7 Feb. 1967.X

- Childers interview.X

- Reyes interview, 19 Jan. 1973.X

- House Subcommittee on NASA Oversight of the Committee on Science and Astronautics. Investigation into Apollo 204 Accident: Hearings, 90th Cong., 1st sess., 1: 498 ff.X

- Erlend A. Kennan and Edmund H. Harvey, Jr., Mission to the Moon (New York: William Morrow and Co., Inc., 1969), pp. 115-16, 147n. This book is highly critical of NASA and the space program, with special emphasis on the 204 fire.X

- Chauvin and Reyes interviews, 6-7 Jun. 1974.X

- Report of Apollo 204 Review Board, app. D, panel 7, p. D-7-12.X

- Ibid., app. B, p. B-142, testimony of Clarence Chauvin.X

- Ibid., p. B-145, testimony of William Schick.X

- Report of Apollo 204 Review Board, app. D, panel 7, p. D-7-13.X

- Ibid., pp. D-7-4, D-7-5.X

- Ibid., app. B, pp. B-153, B-154, testimony of Gary W. Propst; p. B-159, testimony of A. R. Caswell.X

- Ibid., p. B-91, testimony of Bruce W. Davis.X

- Ibid., p. B-39, testimony of D. O. Babbitt.X

- Report of Apollo 204 Review Board, app. D, panel 11, p. D-11-36. At least one member of the Pan American Fire Department, James A. Burch, testified that he had arrived in time to help open the hatch - even though he admitted the trip to the gantry took from five to six minutes and ascent on the slow elevator consumed two minutes more. Ibid., app. B, p. B-177.X

- Time, 10 Feb. 1967, p. 19.X

- Newsweek, 13 Feb. 1967, pp. 96-97.X

- The Sunday Star, Washington, 21 May 1967.X

- Quoted in Today, 14 Apr. 1967; 14 May 1967.X

- New York Times, 4 Apr. 1967.X

- H. Bliss, “NASA’s in the Cold, Cold Ground,” ATCHE Journal 13 (May 1967): 419.X

- Lyndon B. Johnson, The Vantage Point: Perspectives of the Presidency, 1963-1969 (New York: Popular Library, 1971), p. 284.X

- House Subcommittee on NASA Oversight of the Committee on Science and Astronautics, Investigation into Apollo 204 Accident: Hearings, 90th Cong., 1st sess., 1: 207.X

- Announcement of Dr. Kurt H. Debus, 3 Feb. 1967, “KSC Cooperation with the Apollo 204 Investigation."X

- Time, 10 Feb. 1967, reported rumors of lengthy suffering that preceded the astronauts’ deaths. The autopsy disproved these charges.X

- Aviation Week and Space Technology, 13 Feb. 1967, p. 33.X

- Time, 14 Apr. 1967.X

- Report of Apollo 204 Review Board, 6 Apr. 1967, pp. 5-1, 5-2.X

- Ibid., p. 5-9.X

- Ibid., pp. 6-1, 6-2, 6-3.X

- Atkins interview, 29 May 1974.X

- Report of Apollo 204 Review Board, pp. 6-2, 6-3.X

- Ibid., p. 6-3.X

- House Subcommittee on NASA Oversight of the Committee on Science and Astronautics, Investigation into Apollo 204 Accident: Hearings, 90th Cong., 1st sess., 1: 81.X

- Atkins interview, 5 Sept. 1973.X

- Report of Apollo 204 Review Board, app. B, pp. B-39 through B-146.X

- Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, Apollo Accident: Hearings, pts. l, 2.X

- Ibid., pt. 4, p. 365; House Subcommittee on NASA Oversight of the Committee on Science and Astronautics, Investigation into Apollo 204 Accident: Hearings, 90th Cong., 1st sess., 1: 13.X

- Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, Apollo Accident: Hearings, 90th Cong., 1st sess., pt. 6, p. 541.X

- Ibid., pt. 2, p. 127; pt. 5, pp. 416-17; House Subcommittee on NASA Oversight of the Committee on Science and Astronautics, Investigation into Apollo 204 Accident: Hearings, 90th Gong., 1st sess., 1: 265.X

- House Subcommittee on NASA Oversight of the Committee on Science and Astronautics, Investigation into Apollo 204 Accident: Hearings, 90th Cong., 1st sess., 1: 386-87.X

- Ibid., pp. 390-91.X

- Ibid., p. 391.X

- Ibid., 1: 460-80, 501.X

- Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, Report on Apollo 204 Accident, report 956, 90th Cong., 2nd sess., p. 7; Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, Apollo Accident: Hearings, 90th Cong., 1st sess., pt. 4, p. 319. “Some early tendency to shift blame for the fire upon North American Aviation,” Tom Alexander wrote in Fortune, July 1969, p. 117, “was gradually supplanted by NASA’s admission that the fire was largely its own management’s failure. NASA had overlooked and thereby in effect approved an inherent fault in design, namely the locking up of men in a capsule full of inflammable materials in an atmosphere of pure oxygen at sixteen pounds per square inch of pressure. NASA, after all, had more experience in the design and operation of space hardware than any other organization and was, therefore, more to blame than North American if the hardware worked badly.” In 1972, however, North American Rockwell Corp., North American Aviation, Inc., Rockwell Standard Corp., and Rockwell Standard Co. settled out of court with the widows of the three astronauts who charged the spacecraft builders with negligence. The widows of White and Chaffee each received $150,000, the widow of Grissom S300,000. Washington Post, 11 Nov. 1972.X

- Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, Apollo Accident: Hearings, 90th Cong., 1st sess., pt. 5, pp. 397, 428.X

- Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, Report on Apollo 204 Accident, report 956, 90th Cong., 1st sess., pp. 11, 20.X

- "New Hatch Slashes Apollo Egress Time,” Aviation Week and Space Technology, 15 May 1967, p. 26.X

- William J. Normyle, “NASA Details Sweeping Apollo Revisions,” Aviation Week and Space Technology, 15 May 1967, p. 24.X

- George E. Mueller, “Apollo Actions in Preparation for the Next Manned Flight,” Astronautics and Aeronautics 5 (Aug. 1967): 28-33; “Records of Spacecraft Testing, July 1968,” in files of R. E. Reyes, Preflight Operations Br., KSC.X

- Normyle, “NASA Details,” p. 25; Reyes interview, 30 Oct. 1973; Atkins interview. 5 Nov. 1973. Actually the official reports to Debus during 1966 show no written reports from the Safety Office. Atkins must have reported orally at irregular intervals.X

- Mueller, “Apollo Actions,” p. 33.X

- House Special Studies Subcommittee of the Committee on Government Operations. Investigation of the Boeing-TJE Contract: Hearings, 90th Cong., 2nd sess., pp. 3-9.X

- Ibid., pp. 10, 13-14, 24.X

- "Technical Integration and Evaluation Contract,” NASW 1650, Statement of Work, 15 June 1967.X

- Wagner interview; “Boeing-TlE Goals and Accomplishments,” copy in file of Waiter Wagner, KSC.X