The Launch Directorate Becomes an Operating Center

Growing Responsibilities at the Cape

By the time Apollo 11 put Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin on the moon, Apollo field operations were divided among three NASA installations. Marshall Space Flight Center supervised the development of the launch vehicle, the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston the spacecraft, and Kennedy Space Center assembled, tested, and launched the combination. The actual construction was done by contractors from all over the United States; but generally speaking, management responsibility was divided as described above, with fairly well defined boundaries and a minimum duplication of effort.

This neat packaging was not achieved in a single bound, but was the result of an evolutionary process accompanied by much discussion, some backing and filling, and a few attempts at empire building. A main step in the process was the elevation of the Launch Operations Directorate (LOD), previously part of Marshall, into the Launch Operations Center (LOC) on a par with Marshall. This was a good two years in the doing, during which time Debus had to meet increased responsibilities with limited manpower and authority. Mindful of his difficulties, his superiors at Marshall proposed in the spring of 1961 to expand LOD’s organization to include new offices for program control, financial management, purchasing and contracting, construction coordination, and management services. With President Kennedy’s message of 25 May 1961, it became obvious that the manned lunar landing program was going to be a very big project and that NASA’s launch team at Cape Canaveral would need corresponding status.

General Ostrander requested Debus to develop organizational proposals; he responded on 12 June 1961 with three plans. The first called essentially for the maintenance of the status quo, the second for a launch organization providing administrative support to launch teams from the NASA centers, and the third for an independent Launch Operations Center to serve all of NASA.* All three called for a single point of contact at the Atlantic Missile Range, an in-house capability for monitoring launch operations, and an independent status in master planning, purchasing and contracting, and financial and personnel management. Debus talked over these proposals with von Braun who in turn discussed them with Ostrander.1

The three proposals show Debus leaning over backward to avoid any suggestion of officiousness. He was equally convinced, however, that a successful launch program required an experienced team with full powers at the launch site. He set out this thought some six weeks later in a letter to Eberhard Rees, the Marshall Space Flight Center Deputy Director for Research and Development. The letter was occasioned, not by the reorganization proposals, but by a delay in the assembly of the SA-1 booster at Huntsville. Debus agreed to let the work be finished at the Cape, but made it plain that this set no precedent. Writing to Rees, Debus noted that any MSFC division might prefer to send engineers to conduct the related part of the launch operations. Von Braun had tried this at White Sands and found it wanting. With the Redstone, a permanent launch team had been set up as an integral part of the Huntsville organization, and this had worked well the past nine years. Now, given the complexity of the Saturn, it was the only satisfactory approach.

Placing the responsibility for launch checkout with the Huntsville offices that had designed and built the Saturn could only lead to difficulty. If similar arrangements were made with all booster, stage, and payload contractors, the situation would become impossible.2 Agreeing to the exception for SA-1, Debus insisted that henceforth Huntsville hardware be shipped in as complete form as possible, and after Huntsville’s final inspection. At the Cape, “all participants, including contractor personnel, must be supervised and coordinated by one launch agency.” Debus stated that LOD would perform any function “that has been or will become a standard requirement at the launch site.”3

In the meantime, the Deputy Director of Administration at Marshall Space Flight Center, D. M. Morris, recommended to NASA Headquarters that the Launch Operations Directorate have greater authority and stronger support services under its control. Following on this, Harry H. Gorman, Associate Deputy Director for Administration at Huntsville, wrote Seamans at NASA Headquarters on 26 September 1961 recommending greater financial and administrative independence for LOD. Gorman noted that the distance between Huntsville and Cape Canaveral was producing a communications gap, that LOD’s dependence on Marshall impaired efficiency, and that the increased work load falling on LOD and other NASA elements at the Atlantic Missile Range dictated a larger role for LOD. Gorman suggested that LOD assume responsibility for services still performed for it by Marshall offices in programming, scheduling, procurement, and contracting; that it increase its personnel in some existing support elements; and that it lease off-base facilities near Cocoa Beach to house such activities as financial management, procurement and contracts, and construction coordination. He urged the immediate hiring of 75 more employees.4

The day following Gorman’s letter, Debus completed a second position paper on “Launch and Spaceflight Operations.” He noted “the current expansion of NASA activities, the magnitude and complexity of future space programs, the requirement for rapid overall growth potential and the resulting need for clear lines of responsibility and authority”; and he called for a “competent organization of NASA elements.”5 Debus evaluated two plans in a third proposal on 10 October 1961. The first would put administration and management, general technical and scientific fields, facility planning and construction, checkout and launch, and operational flight control under a single launch organization reporting to NASA Headquarters. The second would leave operational flight control and some aspects of checkout and launch under the individual launching divisions of their parent centers.6

Von Braun supported the first alternative: “This study brings the NASA-wide launch operations problem very well in focus,” he wrote. “I consider Plan I the superior plan for the accomplishment of NASA’s objectives [manned lunar landing in this decade] but its implementation will require a ringing appeal to all centers for NASA-wide team spirit in lieu of parochial interest.”7 Seamans insisted that personnel at Headquarters give major attention to the matter in the next two weeks. Debus was later of the opinion that Seamans initiated the entire discussion.8

Von Braun was correct in assuming that raising LOD to the status of a separate center would meet serious objections from vested interests in NASA. Harry Gorman’s arguments from the administrative standpoint were not seconded in the engineering divisions. Eberhard Rees, for one, leaned against separation; if it should prove necessary, he preferred the alternate plan, wherein a Launch Operations Center would control administration and management, general technical and scientific fields, and facility planning and construction, with the launching divisions of the various centers still controlling their flight operations and some aspects of checkout and launching. Most of von Braun’s staff opposed the separation of the launch team from Huntsville. There was some feeling that they would be working in the factory, while the Debus launch team in Florida would enjoy the action and the spotlight. Heated debates continued through a cold winter.9

- While the public has always tended to identify NASA with manned spaceflight, NASA had from its beginning several unmanned projects. These were managed by such centers as Lewis, Langley, and Ames; in some cases, the vehicles were launched from Canaveral. Completely independent of Marshall, such launches complicated matters for LOD.

The Argument for Independent Status

NASA meanwhile began construction of the Manned Spacecraft Center at Houston in late 1961. This center had its own launch team, first called the Preflight Operations Division, later the Florida Operations Group, with launch responsibility for the current manned space program, Mercury. The entire relationship of LOD with the Manned Spacecraft activities in Houston and Florida needed definition. Would Houston or LOD control Apollo launches? Debus believed “that there would be serious problems if the Manned Spacecraft Center thought the launch group was always being loyal to another Center [Huntsville]. What was needed was a launch Center that could be loyal to any Center.” To summarize the case for an independent launch center: the Florida operation had to be on a par with Huntsville and Houston; it had to have direct access to Washington rather than through channels at Huntsville; and it had to be the one NASA point of contact with the Air Force Missile Test Center - if it was going to provide launch facilities for Apollo in an efficient and timely manner.10

NASA announced on 7 March 1962 that it would establish the center as an independent installation. Debus continued in charge, reporting to the Director of Manned Space Flight, D. Brainerd Holmes, at NASA Headquarters. Theoretically the new Launch Operations Center (LOC) would serve all NASA vehicles launched from Cape Canaveral and consolidate in a single official all of NASA’s operating relationships with the Air Force Commander at the Atlantic Missile Range. NASA replaced Marshall’s Launch Operations Directorate with a new Launch Vehicle Operations Division (LVOD) in Alabama. However, Debus would be director of both LOC and the new LVOD and Dr. Hans Gruene would also wear “two hats” as deputy director.11 The creation of the Launch Vehicle Operations Division under Marshall, but with Debus as director, may seem to reflect a reluctance to grant the Launch Operations Center independent status, but was more likely intended to ensure that the Debus team stayed in charge of the Saturn flight program regardless of its tenure at LOC.

According to John D. Young, NASA Deputy Director of Administration, LVOD was “an interim arrangement to provide additional time to carefully consider to what extent, if any, the electrical, electronic, mechanical, structural, and propulsion technical staffs of the present Launch Operations Directorate of MSFC should be divided between MSFC and LOC.”12 Debus saw the matter in a somewhat different light: “LVOD was strictly a compromise measure to overcome the problem within von Braun’s own group. All of his basic contracts were on incentive fees . . .”; the stage contractors “complained and not unjustifiably, ‘We pamper stages through here [Huntsville], then give them to a crew at LOC who may louse it up.’” Mistakes made at the Cape could therefore reduce a contractor’s payment.13

Debus and Marshall’s Deputy Director Eberhard Rees, acting for von Braun, signed an interim separation agreement between the Launch Operations Center and the Marshall Space Flight Center on 8 June 1962. Of the 666 persons assigned to launch operations for the fiscal year 1962, 375 went to the Launch Operations Office. Independence Day for the Launch Operations Center was 1 July 1962. This arrangement was to hold until the following year when reorganization plans within both NASA centers transferred the Launch Vehicle Operations Division from Marshall to the LOC on 24 April 1963.14

New Captains at the Cape

The Gorman recommendations and burgeoning activity on the Cape sparked an increase in the Debus forces in 1961, well before they became the Launch Operations Center. Lewis Melton, reporting for duty in July 1961, initiated a rapid expansion of LOD’s Financial Management Office, which entailed a move to “off-Cape” office space in the cities of Cape Canaveral and Cocoa Beach. 15

On the recommendation of Maj. Raymond Clark and Richard P. Dodd, Debus requested the assignment of Capt. A. G. Porcher, of the Army Ordnance Missile Center Test Support Office at AMR, to LOD. Debus appointed Porcher LOD liaison officer with the Corps of Engineers for construction matters. Clark served in a similar liaison capacity between LOD and the Air Force. A 1945 West Point graduate, Clark had been with the Missile Firing Laboratory in the mid-1950s and was reassigned to the NASA Test Support Office in July 1960. He served on the test support team that represented both the Air Force Missile Test Center and NASA. The Debus-Davis study brought his skills to the fore. During the next two years he would represent LOD in a series of complicated negotiations with the Air Force.16

In January 1962, the Launch Operations Directorate established its own procurement office - a task previously handled under the supervision of Marshall. Gerald Michaud, the first procurement officer, handled contracts for $30,000,000 worth of support equipment for launch complex 37. Michaud, like Melton, had to seek off-Cape office space.17

The Materials and Equipment Branch of LOD had worked under the supervision of the Technical Materials Branch at Huntsville until the beginning of 1962, when a joint supply operating agreement went into effect. By June 1962 the LOD branch was operating as an independent NASA supply activity.18

In this same period, Debus set up the Heavy Space Vehicle Systems Office with Maj. Rocco Petrone as director. Petrone’s responsibility for the Saturn C-5 included facilities, operations, and site master planning. In the third area, he co-chaired, with an Atlantic Missile Range representative, the Master Planning Review Board that regulated the development of Merritt Island and ensured that site development met NASA requirements.

The direct supervision of facilities on LC-39 fell to Col. Clarence Bidgood, a West Point graduate with a master of science degree in engineering from Cornell, and a survivor of Bataan and four years in a Japanese prison camp. Described as a “no-foolishness hard worker,” Bidgood had packed a variety of experience into his postwar years that included flood control work and construction of U.S. airfields in England. He began working for LOD in November 1961 and took charge of the Facilities Office in February 1962. Bidgood turned his attention in his initial year to three major functions: the acquisition of real estate on Merritt Island and the False Cape; organization of the Facilities Office for the criteria design and construction of LC-39; and the establishment of requirements for LC-39 by the various individuals, firms, panels, and centers involved in Apollo.19

The Launch Support Equipment Office under Theodor Poppel and Lester Owens, Deputy Director, retained the design responsibilities for vehicle-associated support equipment. This group remained at Huntsville in order to coordinate the work of designing and launching the vehicles. At von Braun’s suggestion, Debus took Poppel’s group under his jurisdiction.20

In the enlargement of its staff after 1 July 1962, the Launch Operations Center gave priority to individuals who had performed as administrators in similar areas for LOD; and, for other positions of importance, to Marshall personnel with appropriate skills. Associate Director for Administration and Services C. C. Parker, who had served as Management Office Chief at Anniston Ordnance Depot before joining LOD, interviewed the prospective section chiefs and Debus made his final choice from the candidates recommended by Parker.21

As a result of internal growth and the acquisition of the LVOD personnel in May, LOC’s personnel strength rose almost 400% between July 1962 and July 1963. More offices were forced to seek quarters in the cities of Cape Canaveral and Cocoa Beach. In the case of Procurement and Contracts, the move from military security at the Cape allowed easier access for outside contacts. The location of Public Affairs at Cocoa Beach facilitated relations with Patrick Air Force Base, the contractor offices, and the press.22

Most Launch Operations Center personnel remained on the Cape, where LOD had been a tenant. Some NASA elements continued as tenants in Air Force space for several years. In this period many offices had to get by with inadequate facilities, which impaired morale and reduced productivity. George M. Hawkins, chief of Technical Reports and Publications, pointed out that four technical writers worked in an unheated machinery room below the umbilical tower at LC-34. At one time pneumonia had hospitalized one writer and the others had heavy colds. When it came time to install machinery there, they urgently requested assignment to a trailer. Russell Grammer, head of the Quality Assurance Office, established operations in half a trailer at Cape Canaveral with seven employees. When the staff grew to 13 times that size, his force had to expand into other quarters. The Quality Assurance people worked in such widely scattered places as an old restaurant on the North Cape Road, a former Baptist church on the Titusville Road, a residence on Roberts Road, and numerous trailers.23

Organizing the Launch Operations Center

Recognizing the magnitude of Apollo, NASA Headquarters in late 1962 and early 1963 relieved the manned spaceflight centers of certain other responsibilities. Management of the Atlas-Centaur and Atlas-Agena was transferred from Marshall to Lewis Research Center. In February NASA released LOC from responsibility for launching these vehicles and gave it to the Goddard Space Flight Center’s Field Projects Branch.24

As NASA’s agent, LOC generally furnished support and services for all launches, manned and unmanned, conducted by the launch divisions from NASA’s several centers. But in its chief role as a launch agent for the Office of Manned Space Flight, its principal business during this period was the planning and designing of launch facilities for Apollo. On 10 January 1963 NASA announced that LOC was responsible for overall planning and supervision of the integration, test, checkout, and launch of all Office of Manned Space Flight vehicles at Merritt Island and the Atlantic Missile Range, except the Mercury Project and some elements of the Gemini Project. What the phrase, “all OMSF vehicles,” fails to reveal is that the only other authorized manned spaceflight project at the time was Apollo. Almost all of the work at Houston and Marshall in 1963 was devoted to the manned space program. At the Launch Operations Center, most of the planning and the new construction work was also for manned spaceflight, and this was increasingly Apollo.25

Indeed, the first task was to organize for the construction effort. The Webb-McNamara Agreement of January 1963 (see chapter 5-10) had helped clear the air by firmly establishing NASA’s jurisdiction over Merritt Island. The question of whether LOC was to become a real operating agency or a logistics organization supporting NASA’s other launch teams vas still unresolved. The Manned Spacecraft Center’s Florida Operations, for instance, still received technical direction from Houston. Debus had no place in this chain of command. The transfer of launch responsibility for the Centaur and Agena vehicles from LOC to Goddard Space Flight Center, while a step toward LOC’s concentration on Apollo responsibilities, was a step away from centralization of launch operations. The Launch Vehicle Operations Division remained under Huntsville until April. Several areas of overlapping jurisdiction called for resolution. A few section chiefs were certain that they were best qualified to determine their own functions. As Colonel Bidgood said, “Everybody was trying to get a healthy piece of the action.”26

The publication of basic operating concepts in January 1963 made LOC responsible “for construction of NASA facilities at the Merritt Island or AMR launch site.”27 The LOC Director was empowered to appoint a manager for each project and, in conjunction with other participating agencies, write a project development plan. Debus was also required to prepare a “basic organization structure” for the approval of Headquarters.

Debus submitted the required proposal early in 1963. It called for five principal offices: Plans and Project Management, Instrumentation, Facilities Engineering and Construction, Launch Support Equipment Engineering, and Launch Vehicle Operations.28 As so often under Debus, the changes in title did not involve changes in personnel. To the five key posts, he assigned men for whom the new responsibilities would be continuations of their earlier tasks - Petrone for Plans and Projects, Sendler for Instrumentation, Bidgood for Construction, Poppel for Launch Support, and Gruene for Launch Vehicle Operations. These staff elements carried out the major functions of management, design, and construction of launch facilities and support equipment for the Apollo program. Other staff elements (public affairs, safety, quality assurance, and test support) dealt largely with institutional matters. NASA Daytona Beach Operations, established on 23 June 1963 to represent NASA at the General Electric plant there, made up another element reporting directly to the Center Director. On 24 April 1963, Deputy Administrator Dryden approved LOC’s proposed reorganization - except for the Daytona Beach office, which was approved subsequently.29

Under Petrone were two Saturn project offices, one responsible for the early Saturn vehicles, the other for a larger Saturn to come. Both offices were to plan, coordinate, and evaluate launch facilities, equipment, and operations for their respective rockets. Another office was responsible for projects requiring coordination between two or more programs. Other elements of Petrone’s staff were responsible for resources management, a reliability program, scheduling, and range support. These responsibilities, especially for resources management and coordination, gave Petrone substantive control over the development of facilities, a control he showed no reluctance to exercise fully. Spaceport News, the LOC house organ that began publication in December 1962, described the role that Petrone would play in the new organization in its 1 May 1963 edition. As Assistant Director for Plans and Programs Management, the paper declared, Petrone

will function as the focal point for the management of all program activities for which LOC has responsibility. In this capacity, he is responsible for the program schedule and for determining that missions and goals are properly established and met. He will formulate and coordinate general policies and procedures for the LOC contractors to follow at the AMR and MILA [Merritt Island Launch Area].30

Bidgood organized his division along functional lines, with titles clearly descriptive of responsibilities - a Design and Engineering Branch, Construction Branch, and a Master Planning and Real Estate Office. Most of Bidgood’s personnel came from the former Facilities Office, which he had organized several months earlier around a nucleus of R. P. Dodd’s Construction Branch, the Cape-based segment of Poppel’s former office. He recruited others from such agencies as the Corps of Engineers Ballistic Missile Division in California.31 Bidgood was shortly to retire from the Army and to relinquish his LOC post to another Corps of Engineers officer, the less outspoken but equally competent Col. Aldo H. Bagnulo.

Poppel organized the four branches of his division along equipment responsibility lines, extending in each case from design through completion of construction. One branch was responsible for launch equipment (primary pneumatic distribution systems, firing equipment, and erection and handling equipment); one for launcher-transporter systems; a third for propellant systems; and a fourth for developing concepts for future launch equipment.

Something more should perhaps be said to differentiate the last two divisions. In terms of specific launch facilities and ground support equipment, Bidgood was responsible for what was commonly, if inadequately, called brick-and-mortar construction: the vehicle assembly building, launch control center, launch pads, and crawlerway. Poppel supervised construction of the launcher-umbilical tower, crawler-transporters, and propellant and high-pressure-gas systems. Later, the arming tower was assigned to Bidgood. With the exception of the arming tower (later modified and redesignated the mobile service structure), Bidgood’s area largely involved conventional construction. Poppel’s responsibilities were more esoteric; no one could readily formulate plans and specifications in what were new areas of construction. The two divisions also operated differently. Bidgood’s division used the Corps of Engineers for all contract work, from design through construction to installation of equipment. Poppel’s division depended on commercial procurement and contracting. Although Bidgood and Poppel, like Petrone, reported directly to Debus, and although the organization chart showed no link between divisions, the functional statements in the “LOC Organization Structure” manual assigned responsibility for coordination of launch facilities to Petrone.32

The reorganization also clarified the relationship of Launch Vehicle Operations personnel to MSFC and LOC. Although assigned to LOC for operational and administrative matters, they remained under Marshall’s technical direction for engineering. The “development operational loop” that had characterized the old MSFC-LOC relationship remained. This loop implemented the propositions that no launch team could be effective unless it participated in the development of a space vehicle from its inception, and that planners had to consider operational factors early in the design of the space vehicle and maintain this awareness throughout the development cycle. In representing Marshall contractors at Merritt Island and the Atlantic Missile Range, the Marshall Director retained authority to modify any responsibilities delegated to LOC, to interpret Marshall contracts for LOC and the contractors, and to direct the contractors with respect to contract implementation, including instances when disagreements might arise between LOC and the Marshall stage contractors.33

During these months, LOC spawned a great number of boards, committees, panels, teams, and working groups. In September 1963, C. C. Parker, Assistant Director for Administration, undertook to delineate the spheres and activities of these groups. Six panels dealt with facilities, propellants, electricity, tracking, launching, and firing. Committees handled incentive awards, grievances, suggestions, honors, automatic data processing, and five distinct areas of safety. Boards oversaw property, architect-engineering selection, and project stabilization. The personnel of these groups rarely overlapped, as distinctive disciplines required expertise of a particular nature. A significant team, by way of example, was the LOC MILA Planning Group, appointed by Debus on 6 February 1963 under the chairmanship of Raymond Clark. It looked into unsolved issues in relations with the Air Force Missile Test Center, recommended divisions of responsibility among various elements of LOC, and established priorities to assure cooperation.34 The informality of early operations on the Cape was disappearing in the growth of a mighty endeavor.

In the midst of all this organizational activity, one of the most able men to come to the Cape arrived as Deputy Director of the Launch Operations Center in early spring of 1963. Albert F. Siepert had been NASA’s Director of Administration since its beginning in 1958. This 47-year-old Midwesterner had played a key role in the basic organization of NASA and in arranging the transfer of the von Braun team from the Army. Previous to his work with NASA, he had won the Health, Education, and Welfare Department’s distinguished service award. A fine administrator and a great extemporaneous speaker - he could organize his thoughts in a few moments and speak without hesitation or repetition - he wanted to work in the field and requested a transfer to one of the centers. At LOC, he became responsible for the organization and overall management of center operations and had the further responsibility of maintaining good relations with local communities, the Air Force, the Corps of Engineers, other NASA field centers, and various contractors.35

“Grand Fenwick” Overtakes the U.S. and USSR

In spite of the launchings at the Cape, the development of the Launch Operations Center, the agreements between the Air Force and NASA, the preliminaries for the construction of launch complex 39 and the industrial area on Merritt Island, not all was ultraserious. The Spaceport News for 20 June 1963 carried this interesting headline: “The Duchy of ‘Grand Fenwick’ Takes Over the Space Race Lead.” The article told of the premiere of a British movie, a space satire called Mouse on the Moon, at the Cape Colony Inn on the previous Friday. Distributed by United Artists, the movie was a sequel to the popular The Mouse That Roared of several years before.

The Mouse That Roared had centered around the attempt of the Duchy of Grand Fenwick, a mythical principality near the Swiss-French border, to wage an unsuccessful war against the United States in the hope that the United States would pour millions of dollars into the nation for rehabilitation. Surprisingly, the war turned out to be a huge success for the Grand Fenwick Expeditionary Force. It captured a professor at Columbia University, a native of Grand Fenwick, who had invented the “bomb to end all bombs.” By threatening to use the bomb on all the major nations of the world, Grand Fenwick brought universal peace.

In the sequel, Mouse on the Moon, Grand Fenwick, faced again with a disaster in its main industry, wine-making, requested a half-million-dollar loan from the United States. Instead the United States granted a million dollars to further Grand Fenwick’s space program and show America’s sincere desire for international cooperation in space. Not to be outdone, Russia gave one of its outmoded Vostoks. The scientists of Grand Fenwick found that the errant wine crop could fuel this rocket. They sent the spacecraft to the moon, beating both the American and Russian teams. The U.S. and USSR spacecraft landed shortly after the Duchy’s. In hasty attempts to get back first, both Russians and Americans failed to rise from the lunar surface. As a result, Grand Fenwick’s Vostok had to rescue both crews.

The British stars, James Moran Sterling and Margaret Rutherford, came to Cocoa Beach for the world premiere, as did Gordon Cooper and his family, and many of the dignitaries of the Cape area. For a moment the tensions at the spaceport ceased, and the men caught up in the space race enjoyed a good laugh at their own expense.

Mid-1963: A Time of Reappraisal

“The first and the most truly heroic phase of the space age ended in the summer of 1963,” wrote Hugo Black, Brian Silcock, and Peter Dunn in Journey to Tranquility. “Two years had passed since President Kennedy’s commitment to the moon. They were to the public eye, the years of the astronaut; a period when this strange new breed of man was established as something larger than ordinary life, with gallantry and nerve beyond the common experience.” This vision stemmed from the novelty of the situation, the ruggedness of some of the characters among the original seven, and partly, too, from the nature of the Mercury program. “Somehow one man in a capsule, alone in the totally unfamiliar void, more easily acquires heroic status than two or three men facing the ordeal together.” The last flight of the Mercury series, by Gordon Cooper in May 1963, the authors concluded, “was the last appearance of the astronaut-as-superman.”36

That summer marked more than the end of Mercury, as people began to realize for the first time what the moon program really meant. Before that, Kennedy’s words had mesmerized them. NASA had gone about its work in an atmosphere of public consent and mute congressional approval. It had decided how to go, where to go, and who should go. The general public accepted the basic lines of the gigantic undertaking. Now the very concept of Apollo began to be questioned. When the great debate that Kennedy had asked for two years before finally got under way, scientists began to see that the space program made distorting demands on skilled manpower, economic resources, and human determination. And they began to ask if it was really worth doing. Did we have to beat the Russians? Was this the most important scientific effort we could perform? Was NASA perhaps traveling too fast? The President himself seemed to have his doubts when he began to suggest joint space efforts with the Russians.

The President had not anticipated NASA in this. In March 1963 the Dryden-Blagonravov agreement on space communications and meteorology suggested that cooperation was feasible.37 In an address to the United Nations General Assembly on 20 September 1963, President Kennedy stated that joint U.S.-USSR efforts in space had merit, including “a joint expedition to the moon.” He wondered why the two countries should duplicate research construction and expenditures. He did not propose a cooperative program, but the exploration of the possibility.38

On the next day, Congressman Albert Thomas, Chairman of the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Independent Offices, wrote the President to ask if he had changed his position on the need for a strong U.S. space program. The President replied on 23 September that the nation could cooperate in space only from a position of strength and so needed a strong space program.39

Scientists began to talk of other priorities, such as the declining water table in the West and the challenge of oceanography. Lloyd Berkner, to be sure, still took a strong stand for Apollo, chiefly concerning himself with the project as a national motivating force. He had been one of the original promoters of the launching of a satellite during the International Geophysical Year. Berkner’s grand vision satisfied many on Capitol Hill. But a majority of scientists still seemed to question the entire program. They felt that the President had proposed the lunar landing in a period of panic that had stemmed from the success of Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, first man to orbit the earth, and the disaster of the Bay of Pigs just seven days later. In November 1963, Fortune magazine summarized the discussion in an article entitled, “Now It’s an Agonizing Reappraisal of the Moon Race.” The author, Richard Austin Smith, seconded the President’s suggestion to the Soviets for international cooperation instead of the “space race,” which Smith had originally advocated. Smith discussed three levels of attack on the manned lunar landing program. First, a practical view held that the investment of money and talent in Apollo was out of proportion to foreseeable benefits. Warren Weaver, Vice-President of the Arthur P. Sloan Foundation, had discussed the many alternatives for educational use of the $20 to $40 billion that the moon race was expected to cost. Second, some scientists who were enthusiastic about space exploration feared that Apollo and other man-in-space programs would swallow up the funds that could go to unmanned programs, which they saw as more efficient gatherers of scientific information. Third, a growing number of scientists had reached the conclusion that no appreciable benefits of any sort would come from the Apollo program. Philip Abelson, Director of the Carnegie Institution’s Geophysical Laboratory and editor of Science, the journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, had recently conducted an informal survey and found an overwhelming number of scientists against the manned lunar project. “I think very little in the way of enduring value is going to come out of putting man on the moon - two or three television spectaculars - and that’s that,” Abelson stated. “If there is no military value - people admit there isn’t - and no scientific value - and no economic return, it will mean we would have put in a lot of engineering talent and research and wound up being the laughing stock of the world.” After discussing these three objections to the Apollo program, author Smith admitted that the most persistent justification for the moon race was the matter of prestige. He suggested continuing the space program but abandoning the “crash” timetable in favor of one that placed the moon in its perspective as one way-station in the step-by-step development of space. Apollo with a lower priority could provide benefits, while allowing periodic reappraisal.40

Kennedy’s Last Visit

On 16 November 1963, President Kennedy made a whirlwind visit to Canaveral and Merritt Island, his third visit in 21 months. Administrator Webb, Dr. Debus, and General Davis greeted the President as his Boeing 707 landed. At launch complex 37 he was briefed on the Saturn program. The President then boarded a helicopter with Debus to view Merritt Island, and flew over the coast line to watch a successful Polaris launching from the nuclear submarine Andrew Jackson.41

The next week the President died by an assassin’s bullet in Dallas, The new President, Lyndon B. Johnson, announced he was renaming the Cape Canaveral Auxiliary Air Force Base and NASA Launch Operations Center as the John F. Kennedy Space Center. With the support of Governor Farris Bryant of Florida, the President also changed the name of Cape Canaveral to Cape Kennedy. The next day he followed up his statement with Executive Order No. 11129. In this he did not mention a new name for the Cape, but did join the civilian and military installations under one name, thus causing some confusion. To clarify the matter, Administrator Webb issued a NASA directive changing the name of the Launch Operations Center to the “John F. Kennedy Space Center, NASA,” and an Air Force general order changed the name of the air base to the “Cape Kennedy Air Force Station.” The United States Board of Geographic Names of the Department of the Interior officially accepted the name Cape Kennedy for Cape Canaveral the following year.42

People at the Cape seemed to approve the naming of the spaceport as a memorial to President Kennedy. Up to that time, the Launch Operations Center had only the descriptive name. Debus wrote a little later: “The renaming of our facilities to the John F. Kennedy Space Center, NASA, is the result of an Executive Order, but to me it is also fitting recognition to his personal and intense involvement in the National Space Program."43 Many in the Brevard area, however, felt that changing the name of Cape Canaveral, one of the oldest place-names in the country, dating back to the earliest days of Spanish exploration, was a mistaken gesture. After a stirring debate in the town council, the city of Cape Canaveral declined to change its name.*

* Although efforts to have Congress restore the name “Canaveral” to the Cape failed, Governor Reubin Askew signed a bill on 29 May 1973 that returned the name on Florida State maps and documents. On 9 October 1973 the Board of Geographic Names, U.S. Department of the Interior, did likewise for federal usage.

Washington Redraws Management Lines

On 30 October 1963, NASA announced a revision of its Saturn flight program, eliminating manned Saturn I missions and the last 6 of 16 Saturn I vehicles.* NASA discarded the “building block” concept and introduced a new philosophy of launch vehicle development. Henceforth the Saturn vehicles would go “all-up"; that is, developmental flights of Saturn vehicles would fly in their final configuration (without dummy stages).

George E. Mueller, Holmes’s replacement as Director of the Office of Manned Space Flight, made the “all-up” decision.** Mueller came to his new position from a vice-presidency at Space Technology Laboratories. STL provided engineering and technical assistance to the Air Force on its missile programs, including Minuteman, where the all-up concept was first employed. Despite some mishaps - the first attempt to launch a Minuteman from an underground silo at the Cape (30 August 1961) had resulted in a spectacular explosion - Mueller was confident that all-up testing would save NASA many months and millions of dollars on Apollo.44 At the OMSF Management Council Meeting on 29 October 1963, Mueller stressed the need to “minimize ‘dead-end’ testing [tests involving components or systems that would not fly operationally without major modification] and maximize ‘allup’ systems flight tests.” Two other aspects of Mueller’s all-up concept directly affected the Cape. The OMSF Director wanted complete (emphasis is Mueller’s) systems delivered at the Cape to minimize KSC’s rebuilding of space vehicles. And future schedules would include both delivery dates and launch dates.45

Two days after the Saturn announcement, NASA published a major reorganization that combined program and center management by placing the field centers under Headquarters program directors rather than general management. Previously, center directors had received project or mission directives from one or more Headquarters program directors, while direction for general center operations came from Associate Administrator Seamans. Following the 1 November reorganization, NASA gave the responsibility for both overall management of major programs and direction of NASA field installations to three Associate Administrators: Mueller, Raymond Bisplinghoff, and Homer Newell. The three Manned Space Flight Centers - Marshall, Manned Spacecraft, and KSC - would report to Mueller.46

KSC realigned its organization on 6 February 1964 to conform with the new NASA structure. At the same time, administrative and technical support functions were separated, in an attempt to strengthen both; and the number of offices reporting directly to Debus was reduced, with more authority and responsibility given to the assistant directors. Henceforth in the Office of Manned Space Flight at NASA Headquarters and in the three Manned Space Flight Centers, the functional breakout in all Apollo Program Management Offices would be: program control - budgeting, scheduling, etc.; systems engineering; testing; operations; and reliability and quality assurance. At KSC Rocco Petrone as Assistant Director for Program Management was also head of the Apollo Program Management Office.47

- The Saturn C-1, C-1B, and C-5 were renumbered Saturn I, Saturn IB, and Saturn V in 1963.

- Pronounced “Miller.” Holmes and Webb had clashed over the amount of NASA’s funds that Apollo should receive. Holmes wanted to concentrate almost all of NASA’s resources on the lunar mission while Webb, supported by Vice President Johnson, preferred a more balanced program that would provide a total space capability including weather, communications, and deep-space satellites. When President Kennedy sided with Webb, Holmes departed in mid-1963.

Data Management

On 29 October 1964, the year of the reorganization, in his weekly report to Debus, Petrone stated that his office was preparing a KSC regulation for implementation of the instructions received from Headquarters entitled “Apollo Documentation Instruction NPC [NASA Publication Control] 500-6.” This instruction required the following action from each center: identification, review, and approval of all documents required for management of the Apollo program; “an Apollo document index,” cataloguing all recurring interorganization documentation used by the Office of Manned Space Flight and the contractors; a “Center Apollo documentation index”; a “documents requirement list,” listing all documents required from a contractor - this list would “be negotiated into all major contracts of a half million dollars or over” and would be part of the request for quotation; and a “document requirement description,” classifying every item on the “document requirements list,” its contents and instructions for preparation.48

This instruction, Petrone believed, could provide a strong management tool and eliminate many unnecessary documents. The procedure would classify and catalogue documents and make them readily available to anyone who had immediate need for them. It would force many contractors, especially those who had not previously dealt extensively in government contracts, to clarify in writing the exact nature of their roles in the Apollo program. Throughout the entire program, specific delineation of each phase would bring greater clarity to the respective tasks.

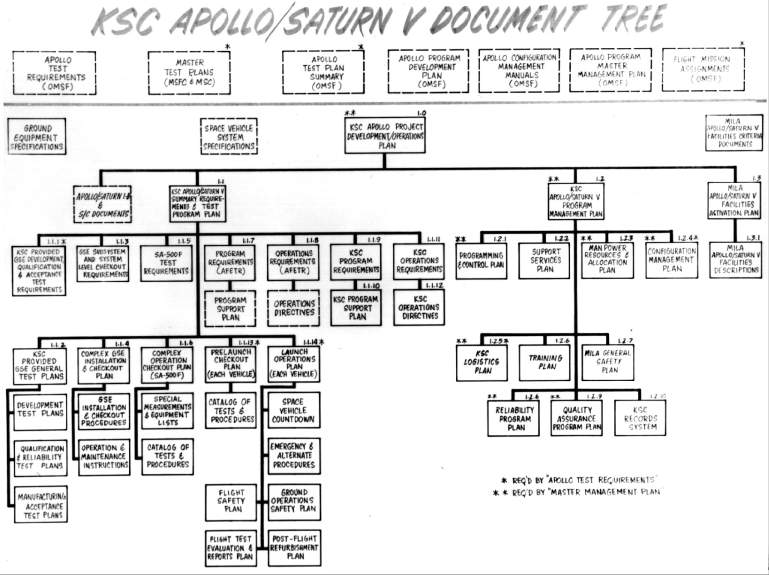

At various times Kennedy Space Center put out Apollo document trees - charts showing the relationship of key documents. On 3 November 1965, for instance, Petrone was to authorize the “KSC Apollo Project Development Plan” under three categories of documents: Apollo Saturn IB Development Operations Plan, Apollo Saturn Program Management and Support Plan, and Apollo Saturn V Development Operations Plan. Within the second category were ten areas of concern to management: program control, configuration management, reliability and quality assurance, vehicle technical support, administrative support, logistics, data management instruction, training, general safety, and instrumentation support. The other two categories had 31 and 44 topics respectively! Typical of those that appeared in both the Saturn I and Saturn V listings were the space-vehicle countdown procedures, the prelaunch checkout plan, and the launch operations plan.49

With even its paper work organized, the Debus team had come a long way from the Launch Operations Directorate of 1960 to the John F. Kennedy Space Center of February 1964. Many problems with the Air Force had been resolved, without undue antagonism resulting. Land on Merritt Island had been purchased for the manned lunar landing program, plans laid for launch facilities and an industrial area, and construction had begun. The center had recruited a roster of engineering and administrative personnel and devised a workable organization.

The new organization did not mean an improvement in every respect. It involved the development of a bureaucracy that was incompatible with the informal, personalized approach of the old days on the Cape. Then the engineers had inspected their instruments, worked on them, sometimes built them; they labored with their hands. Now, they monitored contractors.50 Meetings with department heads and even the Director had been highly informal. Now secretaries scheduled the meetings, each of which required a detailed agenda, and division heads presided with the formality of a college dean at a faculty meeting. Because the men who launched rockets were a sentimental crew, there were frequent references to the good old times. But to launch a rocket that would put a man on the moon, they recognized, required an extensive organization.

ENDNOTES

- Gen. Ostrander, “Proposed Organization for Launch Activities at AMR and PMR,” 6 July 1961; Debus, “Proposed Organization for Launch Activities at Atlantic Missile Range and Pacific Missile Range Due to Proposed Realignment of NASA Programs,” 12 June 1961.X

- Debus to Rees, Dep. Dir. for R&D, MSFC, “Operating Procedures and Responsibilities of MSFC Divisions and Others at Launch Site,” 4 Aug. 1961.X

- Ibid.; see also DDJ, 27 July 1961.X

- D. M. Morris, Dep. Dir. of Admin., MSFC, to Albert Siepert, Dir., Office of Business Admin., NASA Hq., 6 June 1961; Harry H. Gorman, Assoc. Dep. Dir. for Admin., MSFC, to Seamans, 26 Sept. 1961.X

- Debus, “A Paper on Launch and Spaceflight Operations,” 27 Sept. 1961.X

- Debus, “Analysis of Major Elements Regarding the Functions and Organization of Launch and Spaceflight Operations,” 10 Oct. 1961.X

- Concurrence by Wernher von Braun, appended to n. 6 reference.X

- Seamans to Young and Siepert, 13 Oct. 1961; Debus interview, 16 May 1972.X

- Rees to von Braun, “New Organization Proposals for LOD,” 17 Oct. 1961; Debus interview, 16 May 1972.X

- Debus interview, 22 Aug. 1969.X

- NASA release 62-53, “Establishment of the Launch Operations Center at AMR and the Pacific Launch Operations Office at PMR,” 7 Mar. 1962.X

- Young to Seamans, “Internal Organization of the Launch Operations Center,” 29 June 1962.X

- Debus interview, 22 Aug. 1969.X

- "MSFC-LOC Separation Agreement,” 8 June 1962, printed in Francis E. Jarrett, Jr., and Robert A. Lindemann, “Historical Origins of NASA’s Launch Operations Center to 1 July 1962” (KSC, 1964), app.; NASA release LOC-63-64, 24 Apr. 1963. The transfer of LVOD personnel from MSFC to LOC was completed by 6 May 1963. See James M. Ragusa, “John F. Kennedy Space Center (KSC) NASA Reorganization Policy and Methods,” (M.S. thesis, Florida State Univ., Apr. 1968), p. 25.X

- Melton interview.X

- DDJ, 1 Sept. 1961; Clark interview.X

- Missiles and Rockets, 6 Nov. 1961, p. 18.X

- Ernest W. Brackett, Dir., Procurement and Supply, to Dir., Off. of Admin., with enclosure, “Establishment of Launch Operations Center,” 15 June 1962.X

- Clarence Bidgood, “Facilities Office Memo No. 2,” 1 Feb. 1962; Spaceport News, 22 Feb. 1963.X

- Debus interview, 22 Aug. 1969.X

- Parker interview, 14 Feb. 1969.X

- By early June 1962, 930 sq m of off-site space had been leased and plans were made to lease 1,400 more by 30 July 1962. Robert Heiser to Rachel Pratt, “Notes from von Braun,” 11 June 1962; Gordon Harris, Chief of Public Affairs, to Bagnulo, 1 Oct. 1964.X

- Hall to Facilities Program Off., “Justification for Leasing Additional Space in CAC Building,” 13 Mar. 1963. During the period of limited office space, thought was given toward acquiring a barge from the Navy to be moored at the Saturn Barge Terminal and used as an office. Hall to Bidgood, “Barge Anchorage,” 18 Sept. 1962; Hawkins to Hall. “Trailer Request for LC-34,” 1 Mar. 1963; Spaceport News, 13 Oct. 1966, p. 6.X

- NASA General Management Instruction (hereafter GMI) 2-2-9.1, “Basic Operating Concepts for the Launch Operations Center at Merritt Island and the Atlantic Missile Range,” 10 Jan. 1963.X

- House Committee on Science and Astronautics, Subcommittee on Manned Space Flight. Hearings: 1964 NASA Authorization, 88th Cong., 1st sess., pt. 2a, pp. 127, 129.X

- Bidgood interview, 13 Aug. 1969.X

- Seamans to Dir., LOC, “General Responsibilities and Functions of the NASA Center Director,” 10 Jan. 1963, with enclosure, “General Responsibilities and Functions of a NASA Center Director,” 10 Jan. 1963. These documents were circulated in LOC on 18 Jan. 1963; see Office of the Dir., “General Responsibilities and Functions of a NASA Center Director,” 18 Jan. 1963. They were subsequently revised and published as attachments to NASA GMI 2-0-3, “Informational Material on Assignment of Responsibilities in the NASA Organization Structure,” 3 June 1963.X

- NASA GMI 2-2-9.1, “Basic Operating Concepts for the Launch Operations Center at Merritt Island and the Atlantic Missile Range,” 10 Jan. 1963. A 4 Mar. 1963 plan provided for an “Assistant Director for Program Management” (a title actually adopted in the reorganization of 28 Jan. 1964); a 28 Mar. 1963 plan provided for an “Assistant Director for LOC Programs,” as did also a 2 Apr. 1963 plan.X

- The NASA Daytona Beach Operations was established and designated an integral part of LOC in NASA circular 2-2-9, 23 June 1963, which stated that the Manager would “report to the Director, Launch Operations Center, Cocoa Beach, Florida.” See also Debus to George Mueller, “Change in Organizational Structure,” 13 Dec. 1963; Debus to staff, “LOC Organization Structure,” 6 Aug. 1963, and accompanying manual, “LOC Organization Structure,” 2 Aug. 1963; LOC Organization Chart, approved by Hugh L. Dryden, 24 Apr. 1963X

- Spaceport News, 1 May 1963, p. 6.X

- Bidgood, who had joined LOG on 1 Nov. 1962, organized a Facilities Office by late 1962 and published his first organization chart on 13 Feb. 1963. Bidgood interview, 14 Nov. 1968.X

- "LOC Organization Structure,” 2 Aug. 1963.X

- Spaceport News, 1 May 1963, p. 6. For Debus’s views on the “development operational loop,” see his “Analysis of Major Elements Regarding the Functions and Organization of Launch and Spaceflight Operations,” 10 Oct. 1961; also “LOC Organizational Structure,” 2 Aug. 1963, p. 9.X

- C. C. Parker, “Boards, Committees, Panels, Teams and Working Groups,” 25 Sept. 1963.X

- Spaceport News, 30 June 1963.X

- Hugo Young, Bryan Silcock, and Peter Dunn, Journey to Tranquility (Garden City , NY: Doubleday & Co., 1970), p. 158.X

- Rosholt, An Administrative History of NASA, pp. 288-89.X

- The Washington Post, 21 Sept. 1963, p. A-10.X

- Thomas’s letter and the President’s reply appear in Senate Committee of Appropriations, Hearings: Independent Offices Appropriations, 1964, 88th Cong., 1st sess., pt. 2, pp. 1616-18.X

- Fortune, Nov. 1963, pp. 125-29, 270, 274, 280.X

- Spaceport News, 21, 27 Nov. 1963.X

- Executive Order 11129, Designating Certain Facilities of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and of the Department of Defense in the State of Florida, as the John F. Kennedy Space Center, 29 Nov. 1963; NASA announcement 63-283, “Designation of the John F. Kennedy Space Center, NASA,” 20 Dec. 1963; message SAF 82841, Sec. of the Air Force to Cmdr., AFSC, Andrews AFB, 7 Jan. 1964; “Decisions on Geographic Names in the United States, Dec. 1962 through December 1963,” decision list 6303, U.S. Board on Geographic Names (Washington: Dept. of the Interior, 1964), p. 20.X

- Debus to Mrs. W. L. Stewart, 26 Dec. 1963.X

- Ernest G. Schwiebert, A History of the U.8. Air Forces Ballistic Missiles, pp. 130, 201-203, 247; Akens, Saturn Illustrated Chronology, pp. 67-68.X

- OMSF, “Management Council Minutes, 29 Oct. 1963,” 31 Oct. 1963.X

- Rosholt, Administrative History, pp. 289-97. Newell headed the Office of Space Sciences and Applications, Bisplinghoff, the Office of Advanced Research and Technology.X

- NASA release KSC-10-64, 6 Feb. 1964; KSC, “NASA Organization Chart,” 28 Jan. 1964; Spaceport News, 13 Feb. 1964.X

- "KSC Notes,” Petrone to Debus, 29 Oct. 1964.X

- "Kennedy Space Center Apollo Document Tree,” approved by Rocco Petrone, 3 Nov. 1965, Joel Kent’s private papers.X

- Childers interview, 7 Nov. 1972; Gramer interview, 21 Sept. 1972.X